The American Founding Fathers were perhaps the bravest and most pioneering figures in the history of man. Never before had a people tried to break away from a global superpower to form a new country, knowing that what they were doing was considered the highest treason in Great Britain. The Founding Fathers put everything on the line, their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor, to create a new nation of free men and women based upon the principles that all men were created equal. This experiment in democracy was unheard of at its time, and when the United States of America was declared a nation independent from the British Empire on July 4, 1776, the Founding Fathers knew that there was no turning back.

So, in honor of our Independence Day, let’s take a look at eight famous, or infamous, Founding Fathers and signers of the Declaration of Independence whom history has allowed to fall into obscurity.

Elbridge Gerry: The Man Who Gave Us Gerrymandering

Elbridge Gerry was a well-to-do shipping importer from Boston before the outbreak of the American Revolution, working alongside Sam Adams. When Gerry was called upon by the Second Continental Congress, he served as one of the delegates from Massachusetts. During his time in the Second Continental Congress, Gerry proved to be an inconsistent character when war finally erupted between England and the colonies. He advocated for increased funding for the Continental Army and better weapons and uniforms, but when it came to soldiers’ pay he rejected it as a waste of money.

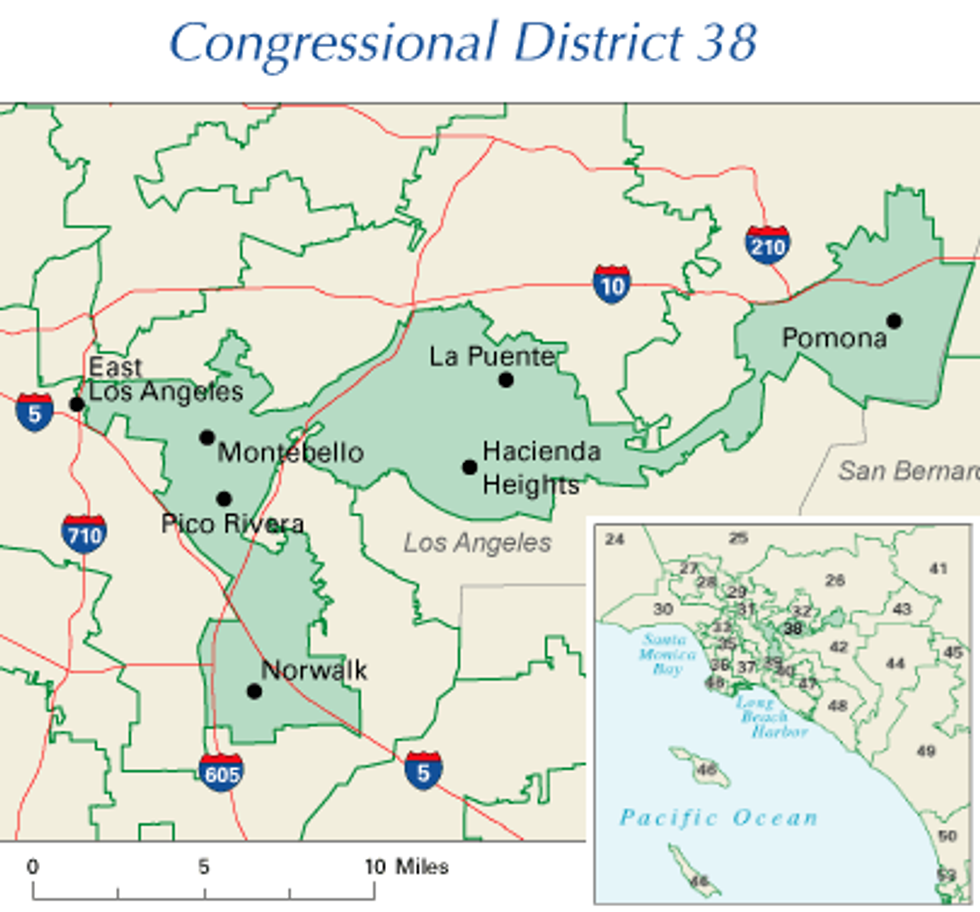

Gerry didn’t exactly work well with others either. When the war finally ended, Gerry found himself chosen by the state of Massachusetts to represent them at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. There Gerry advocated for democratic principles but stopped short at agreeing that congressmen and senators should be elected by the people. One delegate even quipped that Gerry “wouldn’t vote for anything unless he proposed it.” Following the Constitution’s final drafting, Gerry refused to sign it because it lacked the Bill of Rights. Returning to his home state, Gerry ran for governor of Massachusetts after joining the Federalist Party. Finally elected on his ninth attempt, Gerry found himself with the ability to redraw the districts of the State Senate to give the Federalist Party the advantage in the next election.

One political cartoonist remarked one of his districts looked like a salamander, and thus Gerrymandering became a term (example pictured below). Gerrymandering is considered one of the most undemocratic functions of American government. Shortly after his planned failed and the Federalists were unable to gain control of the state, Gerry switched to Jefferson’s Republican Party which angered many of his constituents, propelling him to the Vice Presidency which he only served a year of before dying. Many felt betrayed by his constantly changing views, but to Gerry it was all political sport. Gerry pretty much represents the archetypal two-faced congressman.

Samuel Huntington: The First (kinda) President of the United States

Samuel Huntington was a member of the Continental Congress from Connecticut during the Revolutionary War. While in Congress, Huntington was chosen to serve as the President of the Continental Congress, then a position with less power than the Speaker of the House. Huntington’s position changed in March 1781 to President of the United States in Congress Assembled when the Articles of Confederation went into effect. However, the Articles of Confederation gave him next to no power and the United States was still just a collection of sovereign states.

During his time as President, Huntington presided over meeting with dignitaries, convening war councils with generals, and overseeing the Continental economy. It wasn’t until the emergence of a strong federal government and three branches of government made the United States a single nation with a single leader in 1787 that the President of the United States actually became the leader of the executive branch with actual powers. Huntington resigned just four months into his presidency and nine other men served in the position until George Washington became the first President of the United States of America. Or, the eleventh if you consider Huntington to be the real first.

William Hooper: The Man Who Feared Democracy

Although the Founders were truly great men, many of them were also snobs. Hooper was a North Carolina lawyer and a member of the Southern gentry that looked down upon the lower classes. After signing the Declaration of Independence, Hooper left the Continental Congress after making various statements that made him appear to hold Loyalist sympathies, especially toward American democracy. Returning to North Carolina, Hooper was on the run from the British while supporting the American war effort and eventually contracted malaria.

Hooper ended up living on the generosity of fellow Patriots in his state while the British burned his estates down in their search to capture the Signers. Ironically, Hooper nearly lost everything during the war. When he was reunited with his family in 1783 after being trapped in the British-occupied city of Wilmington, Hooper and his family were nearly broke. But instead of learning a lesson, Hooper remained snobbish until his death in 1790.

Robert Morris: The Man Who Financed the Revolutionary War

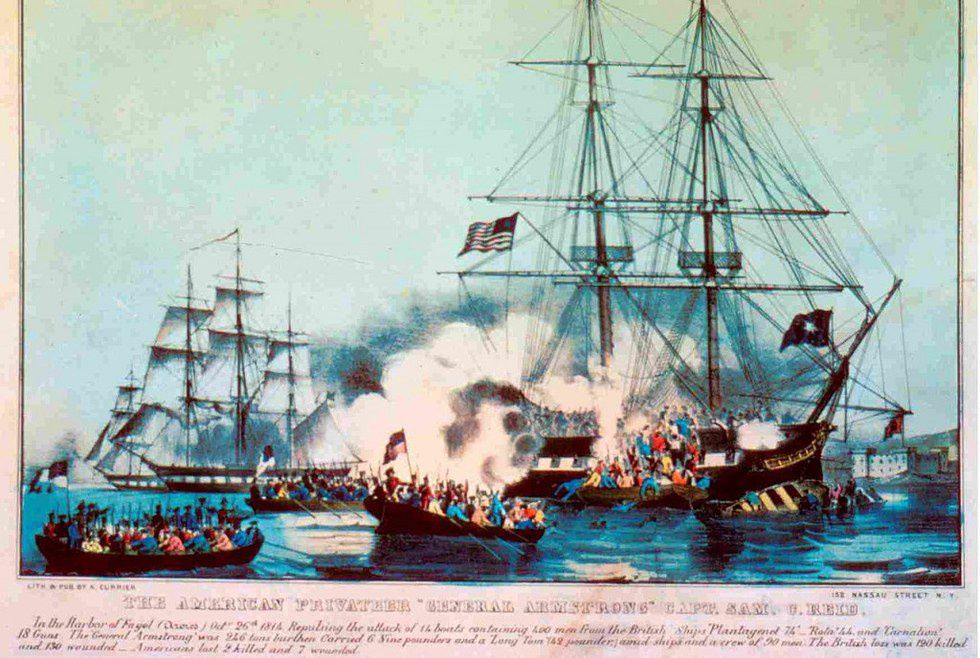

Robert Morris was the leader of a prominent shipping firm in Philadelphia prior to the war. When he was elected to the Continental Congress, Morris chaired the committee that financed the conflict. He founded the Secret Committee for Trade in 1775 and found ways to circumvent British blockades with French and American ships to bring war materials to the Continental Army. In addition, he made it possible for American merchants to continue trading with the rest of the world during the height of the British blockade which kept the American economy on track.

Perhaps Morris’ largest contribution was paying $10,000 to George Washington’s troops to keep the Continental Army together prior to the decisive Battle of Princeton. Morris also helped finance the construction of the first warships of the Continental Navy and channeled the finances to pay for privateers to assault British shipping and sell their spoils to continue financing the American war effort. In addition to also administrating the Continental Navy, Morris made it possible for the war to continue on the seas.

George Clymer: The Nation’s First Treasurer

George Clymer was an orphan turned brilliant banker who loved books as much as he loved money. Clymer’s business savvy was learned from his uncle who adopted him after his parent’s deaths. Clymer acted like a clueless playboy in public, a cold and calculated demeanor in Congress, and a warm, intelligent, and jovial spirit in private. Good friends with Benjamin Rush, Clymer knew all of the Signers very well through his years as a socialite and philanthropist where he honed his people skills. Clymer’s biggest skill however was crunching numbers.

While Robert Morris financed the war, Clymer found ways to collect taxes from the colonies as well as find ways to finance logistics for the Continental Army. On the homefront, Clymer was also involved in numerous committees and active in managing economic and agricultural affairs. During the winter of 1776, trade routes to Philadelphia were cut off by the British and the city was suffering severe food shortages. Yet Clymer and his committee found a way to bring food and relieve the starving city. Clymer, also my direct ancestor, had eight children though only four lived to adulthood. Clymer served one term as a representative from Pennsylvania in the US Congress from 1789-1791. He then retired after his two-year term as a US Congressman expired.

Charles Carroll: The Only Catholic and Longest Living Signer

Charles Carroll came from a prominent Maryland family that had deep roots in politics. Carroll however was disinterested in it as Catholics were often barred from holding office in his home colony. However, when the American Revolution began he found himself seated in the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. During the Revolutionary War, Carroll served on the Board of War which provided oversight to the Continental Army and served as a prototypical Department of Defense. Carroll’s views on slavery were also provocative to people of Maryland at the time.

Carroll found slavery to be evil, though his family and its wealth were built upon slavery. Carroll was one of the first Signers of the Declaration of Independence to advocate for the end of slavery but recognized its immediate abolition would destroy the Southern economy. Several of Carroll’s propositions to slowly end slavery were shot down by the Maryland legislature. Carroll would outlive all the signers including John Adams and Thomas Jefferson who died on the same day fifty years after they signed the Declaration: July 4, 1826.

Richard Stockton: The Only Signer to Recant the Declaration

Hearing word of his capture and his illness, General Washington offered a prison exchange with the British for Stockton’s return. Instead they received news that Stockton was to be released after accepting a British plea deal stating he would recant his support of independence and return to private life after swearing allegiance to the King. As a result, all members of Congress and every soldier and officer of the Continental Army was forced to take an oath of allegiance to the US government and the cause of independence.

Francis Hopkinson: The Designer of the American Flag

Hopkinson chose 13 red and white stripes with a blue field featuring thirteen stars arranged to represent the 13 colonies united under one cause. Following the Flag Resolution of 1777, the new US flag was hoisted throughout the fledgling nation and each regiment and each ship in its military. Hopkinson, not known for his modesty, shocked the Continental Congress when, in 1781, he demanded only a quarter of a cask of wine as his compensation for creating the American flag. The first national flag is shown below.

So there you have it. Although history has forgotten much of what these Founding Fathers accomplished, their triumphs still exist among us today. Most of these men were great people who have been revered over the centuries. Others, like a few mentioned above, left behind a more infamous legacy.

These men lived lives that really mattered and really made a difference for the nation they fought so hard to create.

But the rest, as they say, is history.