There is a prevalent misconception that ancient Egypt practiced a form of pagan polytheism. This is partly due to literal interpretations of Egyptian illustrations and hieroglyphs, and also due to cultural prejudice. Dr. Ramses Seleem, a professor of Egyptology at Cairo University, remarks that "Too many western scholars of the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries arrogantly believed that their civilization was the most advanced. They tended to dismiss ancient cultures as superstitious, barbaric, primitive, uncivilized, and sometimes weird" (Ramses Seleem, The Illustrated Egyptian Book of the Dead: A New Translation with Commentary [New York: Sterling, 2001], 17). But a correct reading of Egypt's sacred texts reveals a deity alarmingly similar to the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Unlike pagan religions, ancient Egypt did not worship animals and forces of nature. Rather, they utilized an advanced system of symbols as artistic and literary mnemonic devices which matched scientific laws with corresponding animal characteristics. Ancient Egyptians would likely regard an accusation of polytheism as blasphemy. “In fact," Seleem says, "ancient Egyptians believed in one God without name, gender, shape, or form. They gave this great, supreme power—which made the earth, heavens, seas, sky, men and women, animals, birds, and creeping things, and all that is and all that will be—the names Emen-Ra (‘the hidden light’), Atum-Ra (‘the source and end of all light’), and Eaau (‘power that has been polarized and expanded, creating the universe’)” (Seleem 16). That's a pretty powerful declaration. It's a doctrine on which most Jews, Christians, and Muslims could agree.

The above description of God reveals his office as the Creator of the world. Seleem quotes Mariette Bey’s description of the principal monuments displayed in Cairo’s Egyptian Museum: “At the head of the Egyptian pantheon soars a God who is one, immortal, uncreated, invisible, and hidden in the inaccessible depths of his essence; he is the creator of the heavens and of the earth; he has made everything which exists and nothing has been made without him; such is the God who is reserved for the initiated of the sanctuary” (Seleem 19). And such is the God of the world's major monotheistic religions.

Bey's words reflect the apostle

John’s description of the Creator God of light: “In the beginning was the Word,

and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning

with God. All things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made

that was made. In him was life; and the life was the light of men. And the

light shineth in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not” (John 1:1-5).

This creative light shines through God's Egyptian names, "The Hidden Light," and "the Source and End (Alpha and Omega) of All Light."

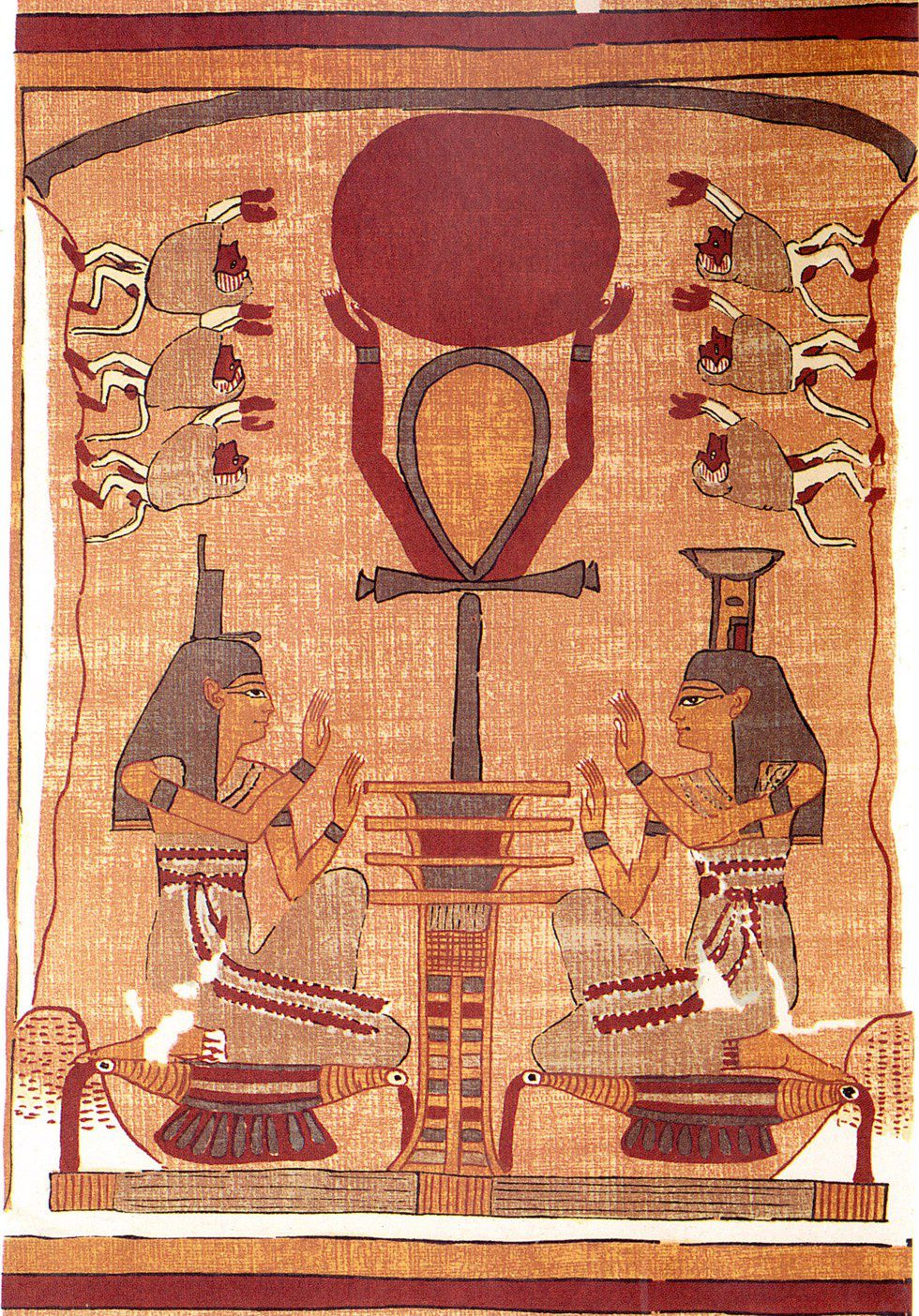

How is this Creator depicted in Egyptian myth? Was it even permissible to illustrate such a God? The Ten Commandments, which were given to Moses shortly after Israel's escape from Egypt, specifically forbade any plant, animal, or human depictions of the Creator as well as the worship of any such image. Seleem elaborates with a translated passage from Calendrier de Jours Fastes et Néfastes by François Chabas: “The one God, who existed before all things, who represents the pure and abstract idea of divinity, is not clearly specialized by (any) one single personage of the vast Egyptian pantheon… the innumerable gods of Egypt are only attributes and different aspects of this unique type” (Seleem 19). So the ancient figures do not, after all, depict gods, but rather characteristics of the Creator. The sum of these characteristics is not unfamiliar to our present world.