Donald Trump’s election to the presidency is in part a story of a populist revolt against an economy evolving by globalization. For the few decades now, the world economy has moved at a dizzying pace, during which industries such as finance and technology have transformed the way we live and work. At the same time, industries that have been the bedrock of stability and prosperity, such as manufacturing, have moved far away from the people they once gave comfort to. Politicians across the developed world have capitalized on this phenomenon and led a populist revolt driven by disaffected workers who face economic stagnation. The election of Donald Trump is the latest and most significant example.

Let’s say that the modern world economy came into being when international trade first started, whenever that was. The world economy has changed more in the past few decades than it has since the advent of the world economy. Traditionally, governments use a variety of measures to limit the flow of international trade. Governments usually do this at the behest of domestic industries because they don’t want to face competition from abroad and lose industry share to foreign producers. (Excuse me while I shamelessly promote myself here). In recent decades, however, it has been the official policy of every U.S. administration to lower barriers to trade to increase international trade, thereby increasing overall economic activity. Free trade agreements like NAFTA opened up borders for companies to do business in other countries without jumping through absurd legal hoops. NAFTA in particular transformed economic relations among the U.S., Canada, and Mexico and did a lot to maintain peaceful relations among the countries. But there have been drawbacks.

To make a long story short, American producers shifted a lot of jobs, much of which was manufacturing labor, over to Mexico because labor was cheaper. This gave American consumers access to cheaper goods and was great for the bottom line for corporate America, but it also deprived a lot of Americans of well-paying, low-skill manufacturing jobs.

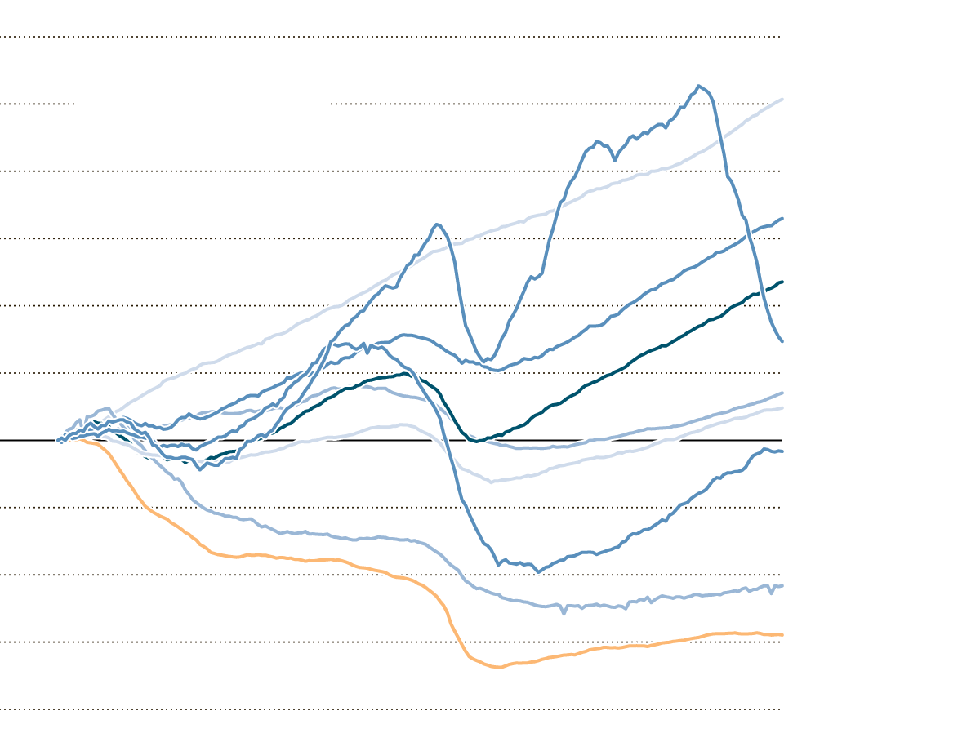

See that orange line that looks like it can't catch a break? It shows that manufacturing jobs have declined by almost 30% since 2000.

Free trade agreements like NAFTA are not the sole reason why labor is offshored to low-wage countries. China is effectively the world’s manufacturer and one of the United States’ largest trading partners, despite the lack of a free trade agreement between the two countries. There are several factors that shape economic relations, like currency valuation, the status of labor markets abroad, the declining cost of shipping of goods from producer markets to consumer markets, government policies that attract foreign investors, and much more. Countries all over the world compete with each other to attract foreign companies to invest because they often inject jobs and capital into a local economy. Free trade agreements simply make it easier for companies and countries to do all this by establishing a legal framework around which international trade operates. Again, there are tremendous benefits to this network of international trade and the modern day world economy is completely built around it. Nevertheless, there are people all over the developed world who feel left behind. They feel as though as the fruits of globalization have been reaped by a select few, while the rest were left to dry. Donald Trump has exploited this sentiment and is part of the reason why he was elected.

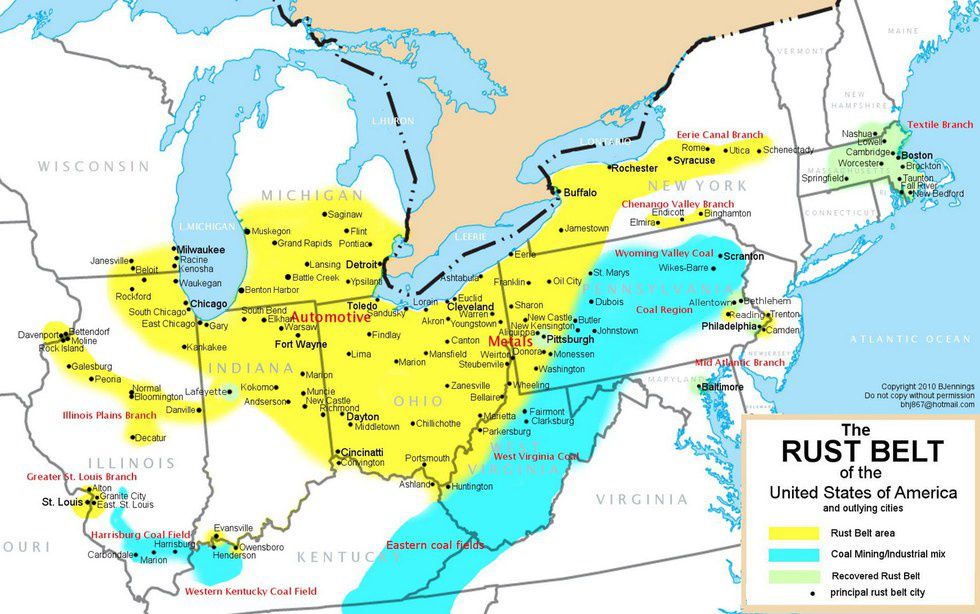

The big stretch of yellow and blue used to manufacturing and coal mining country. Hillary lost most of these states for a reason.

Leaders throughout Europe have also exploited a similar sentiment among their people. Boris Johnson, a British politician and an engineer of Brexit, is a clear example. Driven by fears of immigrant labor and lack of economic progress, the majority of British people voted to leave the European Union, the world’s largest free trade zone. The election of far-right, populist leaders in France, Hungary, and Poland exemplify a similar descent. After Donald Trump’s election, Chancellor Angela Markel of Germany remains as one of the last non-populist driven leaders left in the developed world. (I would just like to point out how ironic it is for Germany to have that status.) A sense of economic stagnation, even decline, has settled in and distressed much of the world.

Donald Trump has evoked an image of having Americans go back to work in the factories and mills that used to characterize the American economy. He has not, however, provided any concrete policy that would allow this. Instead, he has given rhetoric slamming companies like Apple for maintaining manufacturing operations abroad. As president, and with a Republican controlled legislature, Donald Trump will have enormous latitude to accomplish much of the conservative agenda, but there are some forces beyond the power of even a president. Apple will never manufacture one of its products in the U.S. There are simply too many resources, interests, and money invested to keep it that way. Whenever a consumer good is manufactured abroad, it involves a host of industries: the raw materials needed to manufacture the final product; the shipping industry to transport the final good; the labor market in the country of manufacturing; the enormous capital resources invested by the company that the good is being produced for; and many other associated business interests. Not even the President of the United States can control, or even account for, all these factors, regardless of how much bringing jobs back is a priority.

More importantly, though, such manufacturing jobs are not the direction the American economy should lead towards. Such jobs are relatively low-skill and would be low-wage in an American economy wracked by rising living costs. Bringing back such jobs would also raise the costs of consumer goods overall in the U.S. consumer markets. This is precisely what free trade avoids by lowering barriers to international trade. It would be a stunning reversal of longstanding U.S. foreign economic policy and would ultimately hurt U.S. business and consumer interests. Thankfully, it remains stubbornly difficult to do so.