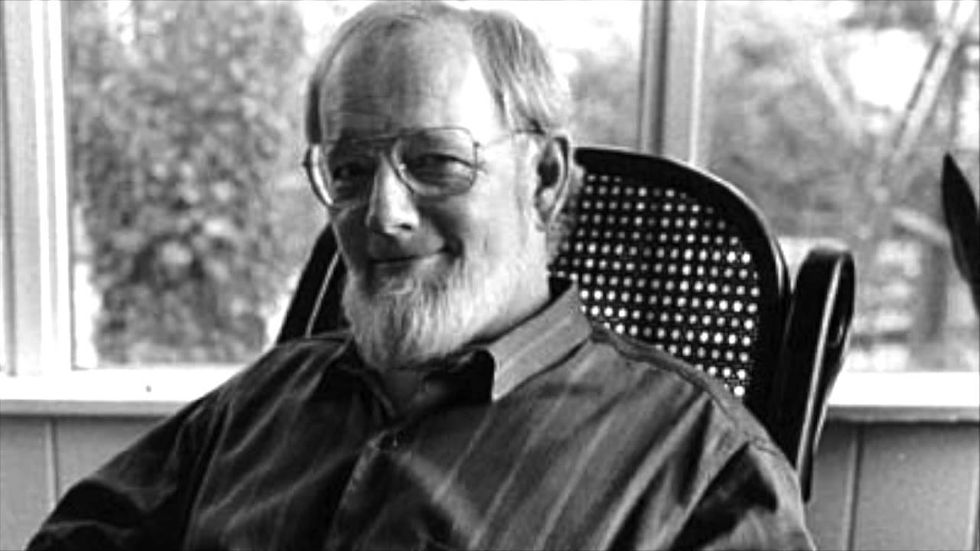

Donald Barthelme was one of the most well known post-modernists of his time. In 1961, Barthelme became director of the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston; he published his first short story the same year. His New Yorker publication, "L'Lapse," a parody of Michelangelo Antonioni's film "L'Eclisse" ("The Eclipse"), followed in 1963. The magazine would go on to publish much of Barthelme's early output, including such now-famous stories as "Me and Miss Mandible," the tale of a 35-year-old sent to elementary school by either a clerical error, failing at his job as an insurance adjuster, and failing in his marriage.

Written in October 1960, it was the first of his stories to be published. "A Shower of Gold," another early short story, portrays a sculptor who agrees to appear on the existentialist game show "Who Am I?" In 1964, Barthelme collected his early stories in "Come Back, Dr. Caligari," for which he received considerable critical acclaim as an innovator of the short story form. His style – fictional and popular figures in absurd situations, e.g., the Batman-inspired "The Joker's Greatest Triumph" – spawned a number of imitators and would help to define the next several decades of short fiction.

Barthelme continued his success in the short story form with "Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts" (1968). One widely anthologized story from this collection, "The Balloon," appears to reflect on Barthelme's intentions as an artist. The narrator inflates a giant, irregular balloon over most of Manhattan, causing widely divergent reactions in the populace. Children play across its top, enjoying it literally on a surface level; adults attempt to read meaning into it but are baffled by its ever-changing shape; the authorities attempt to destroy it but fail.

In the final paragraph, the reader learns that the narrator has inflated the balloon for purely personal reasons, and he sees no intrinsic meaning in the balloon itself, a metaphor for the amorphous, uncertain nature of Barthelme's fiction.

The emotion portrayed in "The Balloon" was quite intriguing. As I was reading it, a thought came to mind: I had completely no clue about the purpose of this balloon. There were negative and positive reactions to this balloon. This balloon was massive, covering “forty-five blocks north and south and six crosstown blocks on either side of the Avenue.”

It was also irregularly shaped, which is why the responses are mixed. Children would jump on the balloon from atop buildings, others would write messages on lanterns and send them up to be hung on to the balloon. Some were “timid” and had a “lack of trust” in what was seen.

But what I realized is that under that random large balloon, we seem to find OURSELVES. We question it, some find it fun, some find it a useful tool.

Now, the real purpose for that balloon was the author’s lack of a love partner since there was no other way to show that other than to blow up a goddamn balloon spread 44 blocks long over Manhattan. However, it became a much deeper meaning to most of the citizens.

Barthelme's famous short story can be read here.