By 1994, Japan was coming out of an economic bubble, and that such bubble popped loud enough to be heard across the globe. This was a nation that had spent almost fifty years in rebuilding and re-imaging itself in order to once again showcase its pride that was blown up by nuclear weaponry to end World War II.

By the time the 1980’s came, Japan was a financial powerhouse, and thanks to their business decisions made by their accomplishments in becoming the second largest economy in the world. This was in part of the Japanese liquidity in the banking system, along with high exports, causing the yen to be worth more than the American dollar (Colombo, 2012). Out of this economic bubble, one group of people emerged from its prosperity, leeching off the bubble economy before the bubble burst, who classify themselves as “Otaku.”

Depending on what side of the Pacific your nation of residence is located, the word otaku has different meanings between the birth place of the word in Japan, and how American has taken it to heart for people who are fans of Japanese culture. To the Japanese, otaku genuinely represents an individual that has made a life-long commitment to a particular hobby.

The hobby can be anything from models, 1900’s wartime history, celebrities, automobiles, and the act of sexual exploration and more. Today in America, the term otaku is a general adaptation of people who like Japanese culture and animation.

In America, there is even a current paperback publication called OtakuUSA, which is a bi-monthly magazine that covers anime, manga and video games from across the Pacific that die-hard American otaku find out more information towards their hobby. Even if the definition between the two countries are different, they are categorized within the same idea; a total obsession for a hobby that engulfs a person’s interest.

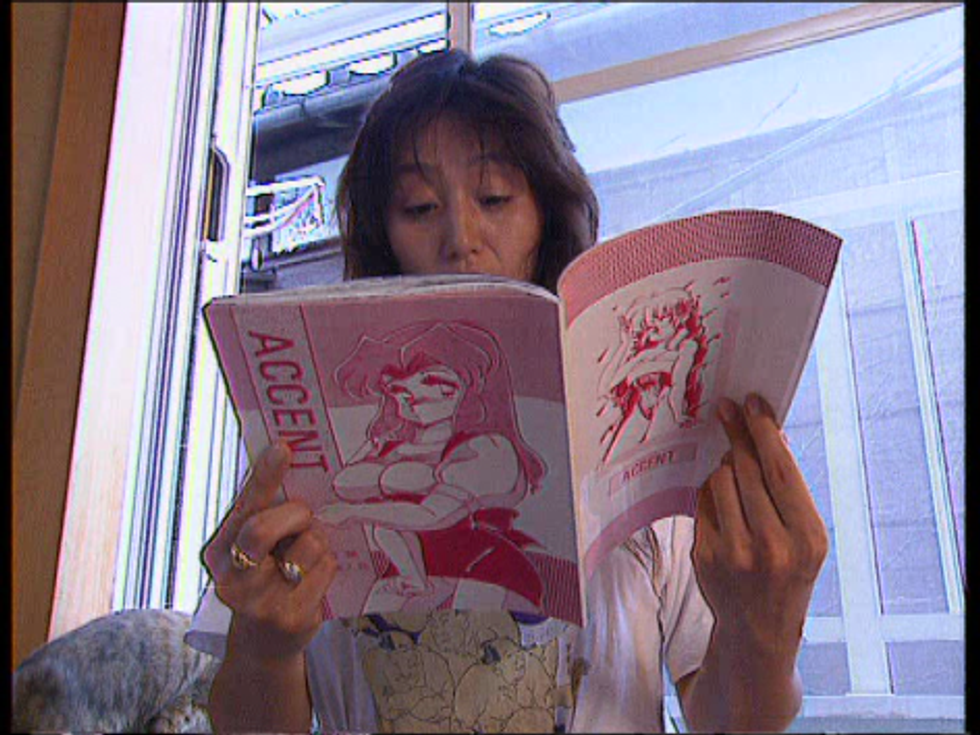

Two French documentary directors, Jackie Bastide and Jean-Jacques Beineix, embarked on a journey to Tokyo, Japan with cameras and questions equipped to document what this whole otaku culture was about. The directors even asked a number of common Japanese citizens if they have heard of the name before, which were mixed responses between “I don’t know” and “Oh, it’s ‘those’ people I don’t want anything to do with.” (Beineix, 1994)

The latter answer seems to be what the negative wording of otaku meant when it came to the arrest of Tsutomu Miyazaki, who was described in the papers as “The Otaku Murderer.” The term otaku received negative attention because of Miyazaki crimes, in which he murdered four school girls over a period of a year, and would practice cannibalism and necrophilia on his victims’ bodies (Associated Press, 2008).

The media seemed to believe that anyone that would collect anime and pornography would be another Miyazaki waiting to happen. From what the documentary showed, that isn’t the case for other otaku in Japan.

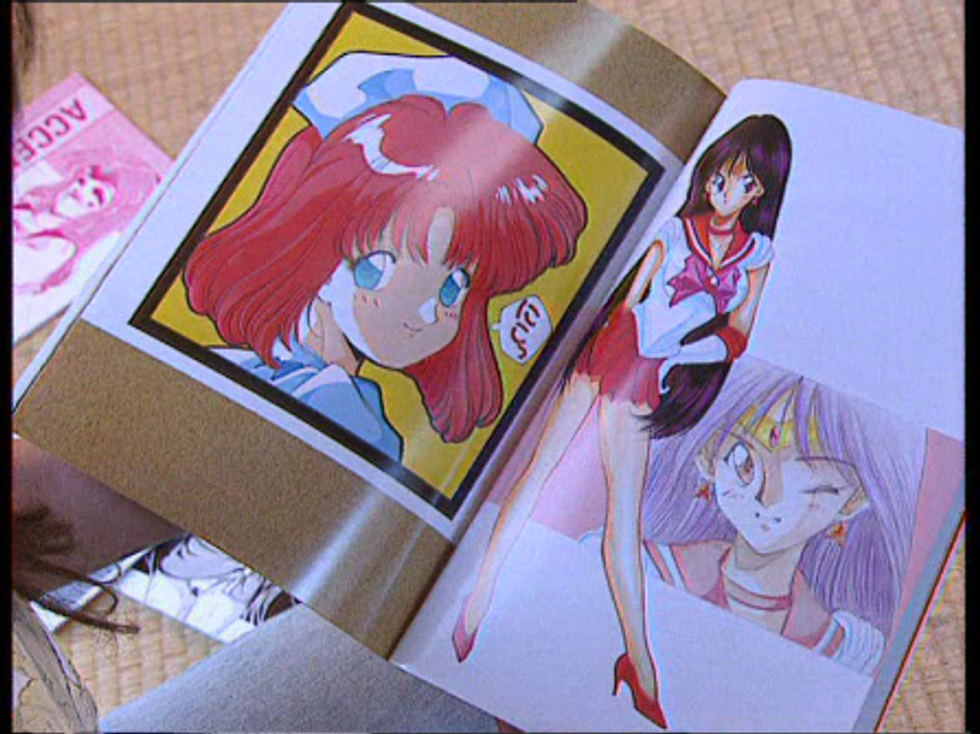

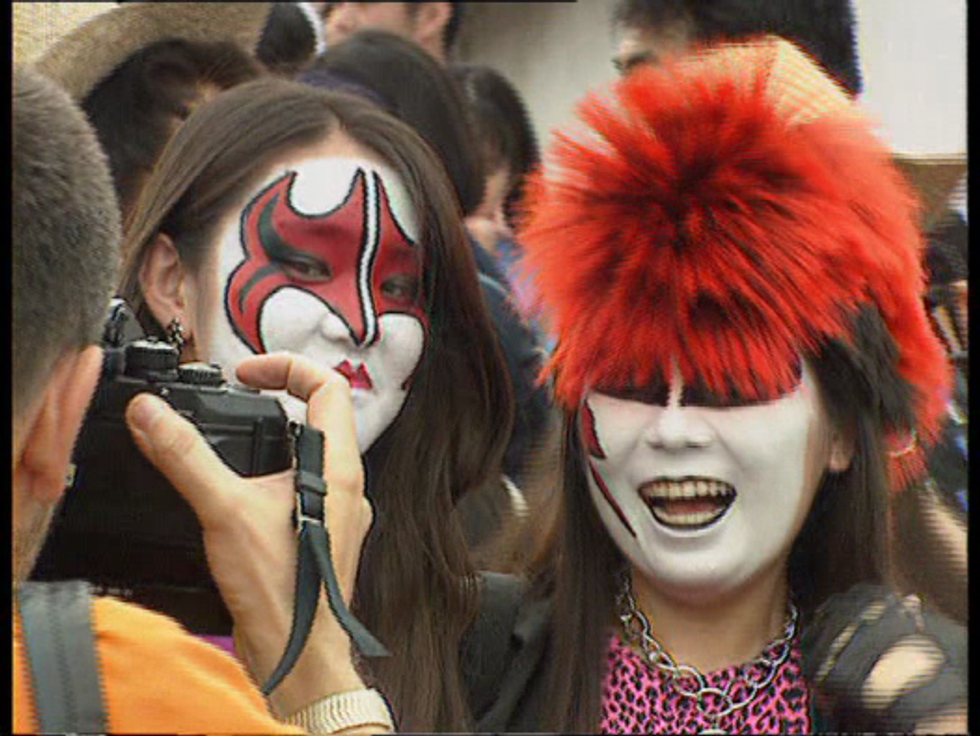

The documentary revolves around a handful of people who consider themselves otaku, which covers from people who are fans of Japanese pop idols, sexual exploration, model kit and resin kit collectors, video arcade fans, and those who share American culture. The only group that seems to be most separated from the de-facto otaku group is a collective of protestors in the streets of Tokyo calling themselves “Tokyo Gagaga.”

Tokyo Gagaga are individuals who see what the economic bubble has done to the society, which is a direct cause of otaku culture to be formed. Their goal is to make the public aware of what is happening with their society being more individually isolated and how they need to be brought together once again as a community (Beineix, 1994).

The people interviewed in the documentary range from different hobbies, with the first focus being on fans of Japanese idol singers and school girl models. Both ends of the fandom were asked why they chose to be in the idol business, and why fans find idols to be their hobby. From the fans perspective, they look at the idol as someone they want to be close too but cannot achieve their status, which makes them more desirable to them.

From the idols and models perspective, it is just a job that they want to do in order to further their career in modeling or acting in the future. The males tend to see female models as a companion, where one otaku collects female figures as a way to replace human interaction with females in the fear of being hurt and rejected by women in real life.

Other otaku are interviewed that collect models as their hobby, but it is along the lines of them going back to a childhood state of mind. One, in particular, focuses his hobby on building model planes, which he is able to balance out his hobby while still doing his duties as being a husband to his wife. This gives a different perspective than the female model collector, which shows that people who are otaku can co-exist with the opposite sex and not be a total shut off from society.

This goes in-line with the theme of war in a nation of peace, where the human interaction element is connected by mock combat with the airsoft otaku, which are individuals who buy replica firearms to shoot plastic bb’s at their opponents in a local forest area. The directors gave another perspective of otaku being in a social setting, even if their activity reflects a violent conflict through simulated fantasy.

The airsoft otaku even go as far as to create uniforms of different armies, ranging from the Nazi regime, U.N., Imperial Japanese, and the American armed forces. The film depicts one member of the German faction waving around a Nazi flag, but to the player defense, it is meant to be used as a way to tell factions apart, and not to state that the individual carrying the flag believes in Nazi ideologies.

The other otaku represented in this film cover interest in sexual exploration, where the directors interview three friends who talk about their sexual experiences while the camera is focused on them watching a pornographic film, which the friends don’t see any shame in letting that be on camera.

Another scene focus on a woman and her lover in the act of sexual role play, in which they edit down the fantasy of her being tied up by her captive to fulfill her bondage fantasy. There are even small interviews with otaku who drive around in a car they modify to look like a police car, with full uniform, decal and lights to go with the car. Other otaku show in the film are two guys who are into American motorcycles, and has several scenes showing them loudly roar down the road of a Japanese suburb in their Harley Davidson’s.

The film summarizes the overall underlying theme of the documentary, which states how the people who categorize themselves as otaku are in a state of absolute adolescence. The otaku in the film seem to have interests and ideas of being engrossed into a hobby that the general Japanese public deems “childish” and “immature” to the rest of their society. To the otaku, their hobbies are the foundation to who they are as a person overall, and find true enlightenment through their hobby for their own personal nerd utopia.

This theme is brought up as the last point in the film where a child draws Mt. Fuji which is surrounded by a heavy mist. The message of this is how the otaku use their hobbies to hide themselves from the outside world, with the mist representing their hobbies to shield them from the people around them on who they are (Bieneix, Film). The other item to bring into focus this theme is a toy clown statue, which is the representation of the childish behavior that seems to exist in Japanese society that the culture doesn’t want to deal with.

The viewpoint of the documentary is through the looking glass, that people who are self-identified as otaku seem to be individuals who are children in mind and at heart with their hobbies being part of who they are. One of the experts in the film, by the name Akio Nakamori, gave commentary about the psychological viewpoint of Japanese otaku from his studies at the time of this film. Nakamori also states how the Japanese otaku are described as, “Anyone whose hobby has become a passion is an otaku.” (Bieneix, 1994).

From what I know first-hand of Japanese and American otaku culture is that I see both share that passion, but the repercussions to that seem to carry a childlike mindset that never went away. It seems better for the otaku to remain in his own adult “playpen” than to put away his toys and move with society, and would even go as far as to defend why they are in their pen in the first place. Their childhood bubble is that of the Japanese economy in the 1980’s, either it gets popped for reality to hit the otaku, or the bubble continues to grow more and more.

Some who see this documentary can fall in one of three viewpoints. The first viewpoint being that people who see this might think anyone who has these kinds of hobbies are strange individuals that will never fit in the norm of society.

The second viewpoint states the other opinion of people who look at this documentary as being utterly offensive to people who categorized themselves as otaku, and feel that the message is not in their personal favor and diminishes their hobbies. Lastly, the viewpoint being that what was shown in the documentary is utterly truthful to those who are categorized as otaku, because they are very familiar with the culture of the group by having some part in it as well.

I tend to fully agree with the last viewpoint since the documentary was being fully truthful to otaku culture overall. I can also say, without a doubt, that the truthful perspective is still apparent to otaku culture to this day, twenty-two years after this documentary came out.

If someone really wanted to do some surface digging on both Japanese and American otaku culture, you can see that it is still a money making market to appeal to the twenty and thirty year old man-children that only want to focus on their hobby without trying to merge with regular adult society.

Even with a youthful mentality, this also brings into question how a person’s fun time can be offensive to those around them. They don’t seem themselves hurting anyone by living in their own adult pen, but by not contributing to society and being a leech from the government or outside funding through family to sustain their hobbies, they hurt more than they help on a personal level to those around them.

The otaku are able to send off one message that is kind of hard not to miss, and that is if there is anything going on in the world outside of their hobby, they could care less about it. The example given would be how the model kit otaku only saw the Gulf War as a means to see his favorite aircraft in action, when the purpose of the war politically didn’t interest him one bit (Beineix, 1994). The otaku life is seen through one lens, viewpoint, and factor that anything outside of that is not worth their time. This mindset states the dedication otaku have for their hobby, and only for their hobby.

I wouldn’t say this film is set up as a “scared straight experience” for someone you know who is into a hobby and share the same traits as the otaku are being represented in the film. This film is really a documented account on a cultural and psychological level that shows the viewer a reality that does not get any light to it, unless you know or are in that reality first hand, and can see the faults within it.

On a personal note, I look at this film as a measuring stick to show me what can happen if my hobbies and interests go down a certain path, which does scare me to an extent. This film I think makes it easy to get a grasp on a sub-culture that currently exist today, and is very vocal about it on social media if you happen to take some time to look into it yourself. I overall highly recommend this film to people who want to know a side of nerd culture and its impact culturally and personally.

Sources:

Associated Press (2008, June, 17) Japan executes 3, including serial killer who mutilated young girls. International Herald Tribune. Retrieved from

Beineix, Jean-Jacques (Producer), & Beineix, Jean-Jacques; Bastide, Jackie (Director). (1994). Otaku [Documentary]. France: France 2 Cinema

Colombo, Jessie (2012) Japan’s Bubble Economy of the 1980’s. The Bubble Bubble. Retrieved from http://www.thebubblebubble.com/japan-bubble/