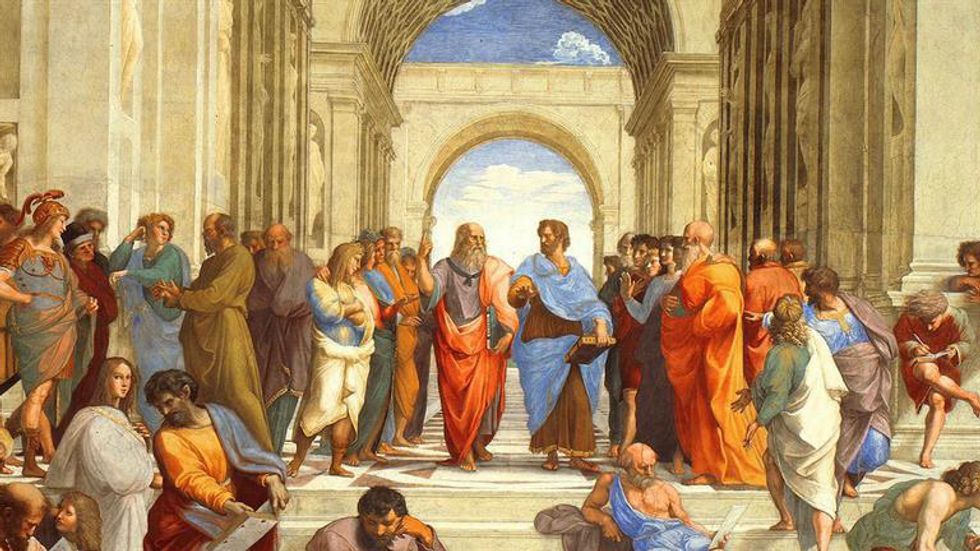

Virtue ethics are those which govern a human being’s actions and determine the character traits of that human being. Of all the ethical theories that exist, virtue ethics is perhaps the most personal. Aristotle initiated the discussion about ethics in Nicomachean Ethics, pondering such fundamental yet profound questions as what is good, what is the objective of human life, and what is happiness. Aristotle defines good as that at which everything aims,[1] adding that knowledge of what constitutes as good is paramount in human development. Virtue ethics emphasizes the importance of self in building character and prioritizes it above social interaction. It accentuates uniqueness in human beings and individualizes one’s character. There is, however, some ambiguity on the definition of “good”; this ambiguity can cause disagreement on what good is between individuals or amongst a society. Additionally, virtue ethics depends on human nature to be virtuous, which can be toxic to a society with individuals whose motives are considered neither good nor virtuous. Because virtue ethics relies solely on one’s personal character, it is the most appealing of the ethical theories to the individual and is the easiest by which to abide.

Immanuel Kant concerns himself with the idea of duty ethics. He introduces the theory of the categorical imperative,[2] which, to paraphrase, is to act in a way that one would want others to act as well. This theory promotes ideas such as fairness, universal equality, and the importance of the individual and human life. Similarly, John Locke’s rights ethics[3] discusses natural rights and the importance of the preservation of human life. However, one idea that this theory avoids is the idea of consequences of an action. While it is sometimes impossible to predict the consequences of an action, one can usually predict a likely outcome; the theory of the categorical imperative focuses on the motivation of an action, which might be altruistic in one’s mind and selfish in the mind of another. The categorical imperative also subtly places value on a person based on their ranking in society and their perceived ability to contribute to it. Lastly, because this theory attempts to combine the idea of the individual with the principle of universality, it can sometimes be difficult to act as one would want others to, as opposed to obeying one’s own intuition and common sense. Duty ethics disregards logical actions in favor of moral ones, which can sometimes be debatable.

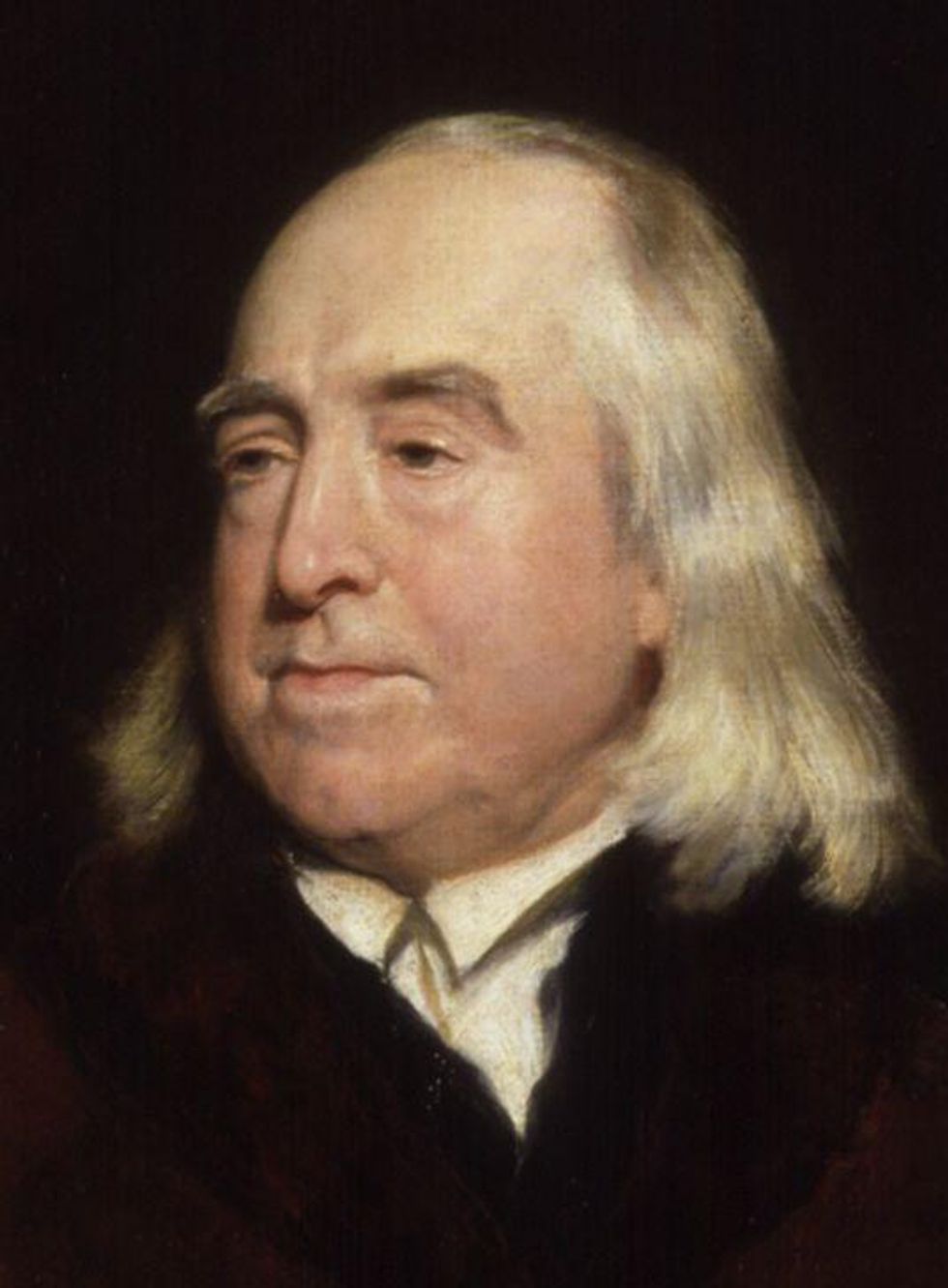

Utilitarianism is a fairly simple code of ethics to follow. As the name suggests, it focuses on the “utility” or the greater good of society as a whole as opposed to the individual. One strength of utilitarianism is that of numbers; it aims to maximize welfare for the most people. One drawback of this theory, however, is that it undermines the individual. It can also be difficult to predict the consequences of an action, and while this is a major emphasis of utilitarianism, it can also minimize welfare if consequences that were believed to occur did not. John Stuart Mill, and particularly Jeremy Bentham, lambast[4] the idea of natural rights by arguing that government is necessary to preserve order and establish laws to which all people of society can abide to. However, if people are not entitled to these natural rights, and if the government cannot possibly enforce all of its laws, it is impossible to assure respect and equal treatment to others; again, the individual is undermined and the greater good is favored. Both Bentham and John Stuart Mill believe that society is governed by pleasure and pain.[5] Mill, however, emphasizes the role of the individual in society and defends the liberty of the individual. This idea of equality of an individual in society strengthens Mill’s argument in favor of utilitarianism.

A solid and well-rounded ethical framework should contain subjective, intuitive, objective, and rational components in it. It should be well-posed, detailed, and offer a solution to any problem that occurs. While this formula sounds good in theory, it is impossible to compose such a framework. With technology perpetually evolving and innovating, new inventions might cause some confusion concerning ethics. Such confusions can best be confronted by an ethical framework that focuses on the individual rather than on society as a whole. Aristotle’s virtue ethics do the best job at this; it is left up to the individual to decide whether something is good or not. Human nature is inherently good—humans act in a manner in which good is done in some form. Virtue ethics minimize disagreements between individuals because it allows for the individual to decide whether or not a decision is ethical and unites individuals on the common ground of the virtues that are agreed upon to be good.

In a similar manner, Immanuel Kant’s and John Locke’s rights ethics emphasize the importance of the individual and the value of human life. They ensure that nobody’s rights are infringed upon, and they allow the individual to decide for itself whether something is good. Because of the volatile nature of consequences of an action, it can be difficult to predict. Therefore, actions should be judged based on their adherence to a set of principles, and not on their consequences. Holding the value of human life above all else prevents questions as to whether a decision to end a life is ethical or moral. Its consequences play out naturally and the importance of the individual is preserved in a society whose greater good is also considered. Prioritization of the individual encourages the individual to become a virtuous and contributing member of society, thereby combining individualism and utilitarianism. Virtue ethics, in the long-run, promotes what is best for society by first promoting the best possible individual. It is impossible for the individual to contribute to society if the individual has nothing to contribute.

[1] See Chapters 1-3 of Book I for a broader discussion.

[2] For an analysis, discussion, and examples of this theory, see “The Categorical Imperative.”

[3] See “Our Rights in the State of Nature” and “Declaration on Euthanasia.”

[4] See Mill’s “On Nature” and Bentham’s “Natural Rights”.

[5] See Bentham’s “The Principle of Utility” and Mills “Higher and Lower Pleasures” for a discussion on the measurement and discernment of pleasure and pain.