It is a thoughtless person who proposes a story to exist in a vacuum from its culture.

This is the issue that arises once again when we confront the recently-announced Netflix film remake of Japanese manga series “Death Note,” which has relocated the characters and setting from contemporary Japan to… Seattle? OK, Netflix, sure. Except it’s actually not OK. In fact, shifting a story like “Death Note” to American soil is a big fat mistake.

Why is this a problem? To help make clear the impact culture has on the recipients of storytelling, I’m going to tell you a fun little anecdote once shared with me in a cultural anthropology class.

Once upon a time in Africa, an anthropologist told a story to the indigenous group of people she was studying. The story was one with which we are likely all familiar: Hamlet, one of Shakespeare’s great tragedies and an iconic literary work of the Anglophone world. The anthropologist believed that the play was universal; that “human nature is pretty much the same the whole world over.” Asked to share her knowledge, she saw this as an opportunity to prove via one of the greatest works in the English language that stories can mean the same thing worlds apart.

It wasn’t just small details that changed in the retelling, it was the entire meaning of themes and motifs throughout the play. Ghosts, family relations, madness, marriage—everything meant something fundamentally different in the context of the indigenous people’s own cultural experience. It turns out a story does, in fact, change when it is told in a different culture. And in the case of Netflix’ upcoming film, one will find that the story changes for the worse.

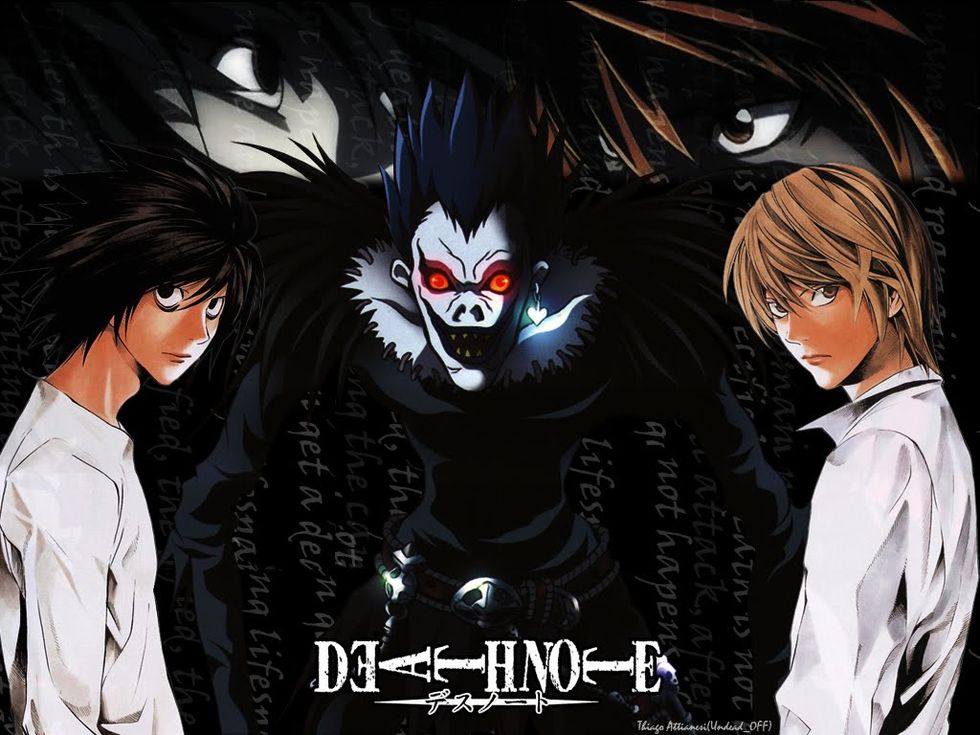

The reason for this depends on an understanding the original story of “Death Note.” In Tsugumi Ohba’s original story, which has since been adapted into many mediums, an intelligent and well-liked teenager named Yagami Light (“Light” is the first name here, as surnames are traditionally given first in Japanese culture) stumbles upon a supernatural artifact called the Death Note. The Death Note, we learn, comes from the world of “shinigami,” or death gods, and is endowed with the power to kill anyone whose name is written in the pages of the book.

There are further rules, complications, and shenanigans, but the basic premise that one must understand is this: Light, who is ambitious and judgmental, decides to use the powers of the Death Note to punish convicted and suspected criminals across the planet by death, cleansing the population of “evil” to create a “new world” of which he will be god. His antagonist (who is arguably the good guy) is the brilliant but eccentric detective “L,” who works with a secret task force including members of the Japanese police in order to identify and capture Light’s deadly persona “Kira.” Overall, the story deals with justice, morality, and determinism – concepts which could surely be considered universal… Until you put them in Seattle, that is.

Aside from the obvious dilemma of how to represent the Japanese concept of shinigami in US culture, and the ethical value of yet again casting a white actor over an Asian-American for a role that was originally Japanese, Netflix’s change in setting reflects a huge shift in something the very plot hinges on: the way each locale’s criminal justice system works.

Here’s some knowledge for the newbies in the crowd: the criminal justice system in America is fucked. (I know, it may come as a shock. Take your time to process.)

Some of the penal system’s structures in the United States make decent sense, like "everyone gets a trial" and "innocent until proven guilty." But overall, the actual impact of incarceration on US soil is to acquire a huge population of poor people, often ethnic or other minorities, and employ them for slave labor. Don’t believe me? Consider that the United States prison population makes up 22% of all incarcerated people in the world, while our entire nation makes up only about 4.4% of the world as a whole. Our incarceration rate is the highest in the world, by the way. Oh yeah, and it’s incredibly racially slanted, with black and latinx populations incarcerated at proportionally way higher rates than white folk. What’s more, 1 in 5 prisoners in the US were incarcerated for drug offenses. That’s almost half a million people. We are also one of the only industrialized countries left to legally try teenagers as adults, and to continue to support the death penalty.

Compare this to the penal system in Japan, most of which operates on an entirely different level. Investigation trumps the judgment of juries, and a suspect rarely proceeds to trial without a confession. Defendants can also trade monetary restitution for jail time, sometimes avoiding it altogether. Police also have the authority to drop charges or refer a guilty person to a rehabilitative program rather than convict them in court. Case details are rarely made public, and Japan’s high conviction rate is partially attributed to the propensity of judges to only take to trial cases which are very certain to result in conviction.

Not all of these qualities are in direct opposition to the legal system of the US, of course (Japan also employs capital punishment, for instance); but they do help inform why Death Note’s character Light/”Kira” might be motivated to pursue further justice upon convicted criminals. In his eyes, they are not being punished to an appropriate extent, and it is necessary to take greater action by sentencing them to death via the supernatural notebook.

Most importantly, though, crime in Japan is not racialized like the US is. While Japan as a nation is certainly not exempt from racism and xenophobia, the population of the country is extremely homogenous, almost exclusively comprised of the ethnic majority of native Japanese. The criminals executed by “Kira” share the same race and skin tone as their killer, for the most part. This is the real crux of the matter: a character targeting criminals in the US and executing them is a fundamentally different story.

In the US, the police are not protectors of the incarcerated, preventing a vigilante from doling out justice; they are perpetrators of violence against perceived wrongdoers, as evidenced by our outrageous records of police brutality, particularly against marginalized populations. Furthermore, the people most likely to be convicted and processed by the criminal justice system are (often low-income) minorities. When this population starts getting systematically murdered to “cleanse” society by a privileged white guy, you can see how the story changes. See, we already have people going around and killing other people they perceive to be criminals. They’re called “cops.”

So when Netflix decided to whitewash, recast, and relocate the story of Death Note, what tale are they really telling? The film’s Western producers say their take on the saga continues to present the concept of “moral relevance — a universal theme that knows no racial boundaries.” But the justice doled out in Death Note doesn’t occur in a vacuum. It is informed by the conventions and realities of the existing penal systems which surround it. One may claim that this transcends racial boundaries, but here in the US, racial boundaries are practically the foundation of our thriving prison-industrial complex, and that can’t be erased from collective memory simply by wishing it so.

There are many good ways to adapt a story. Adaptations of Shakespeare playing on race, location, history, and gender surface every day; many reboots offer greater diversity; some, like the new Ghostbusters, take an equivalent story and somehow make it less gross and more funny. The direction Netflix has taken with Death Note is not that. I can’t pass final judgment on the film before I’ve seen it, but from what I know about America, “Death Note” does not belong in this setting, and I think fans are warranted to express their disappointment.