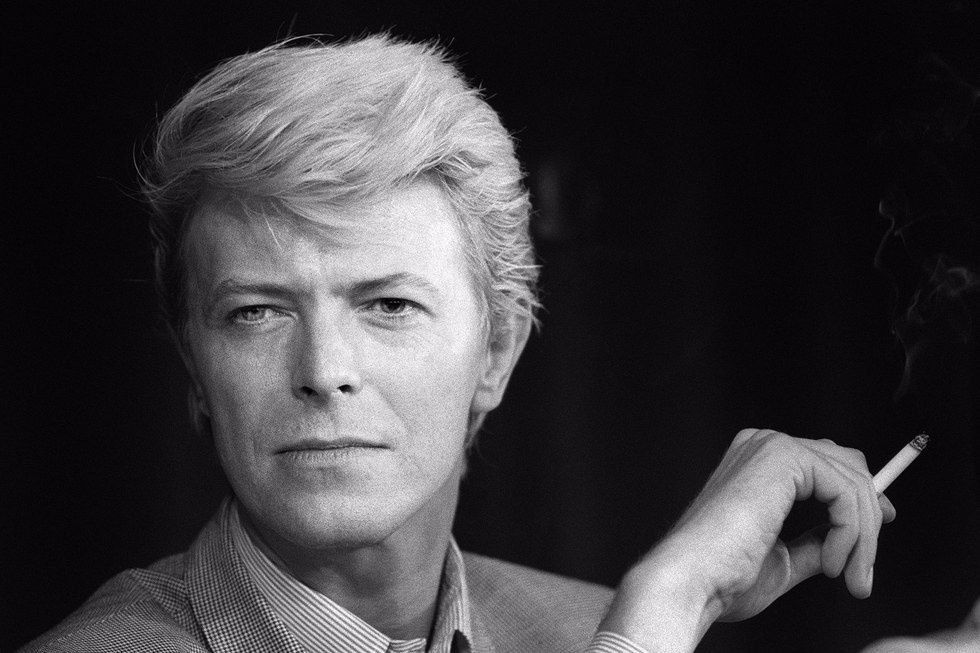

David Bowie (1976-1979)

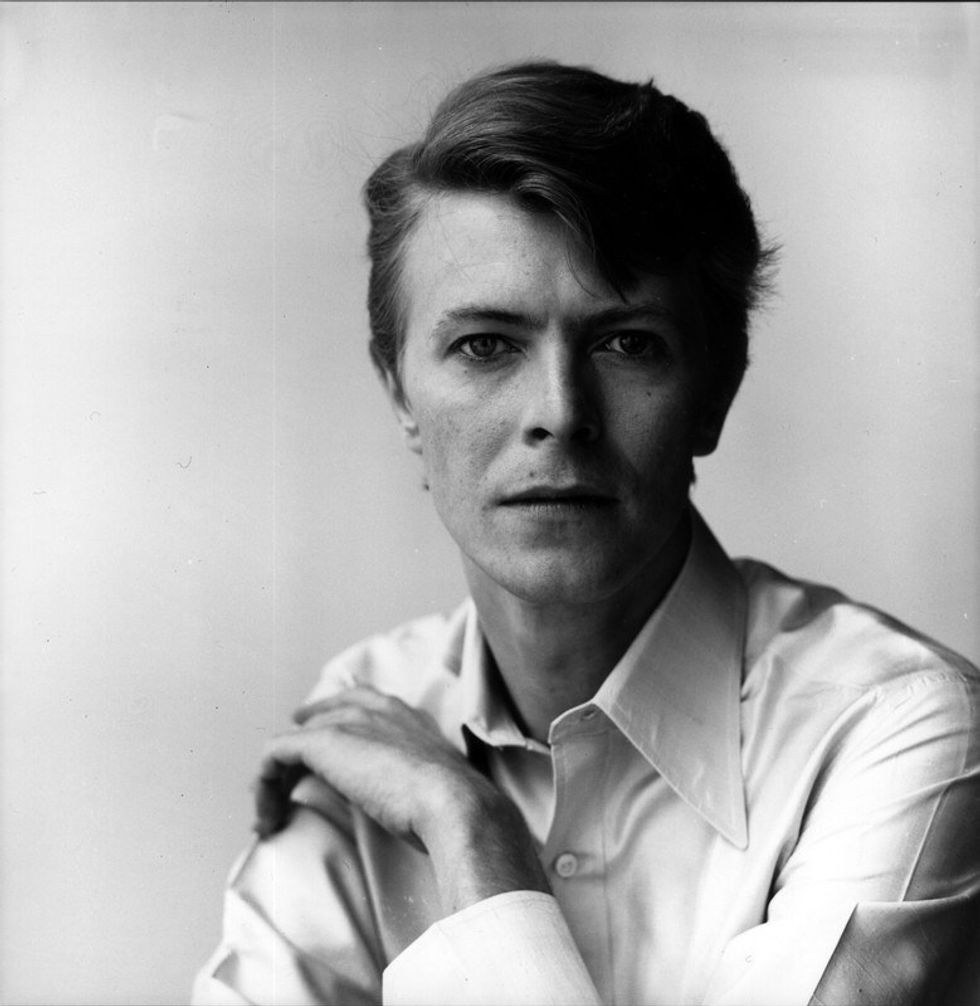

Since his passing in January of this year, hundreds, perhaps thousands of writers have penned tributes to and examinations into the massive and complex career of David Bowie. Twenty-five studio-albums, soundtracks, countless roles in films, concert tours, paraphernalia and a permanent status as an important cultural icon.

This is an examination of a single fragment of the monumental achievements of Bowie, the Berlin Trilogy.

III

1979

Following the end of the "Isolar II" tour in the final months of the previous year, David Bowie returned to Berlin once again with Brian Eno and Tony Visconti for the final album of what would be known as his Berlin Trilogy.

"Lodger," originally entitled "Despite Straight Lines," is perhaps the most under-appreciated of the trilogy, erroneously overlooked. The Low album is championed for its experimental exploits and “Heroes” for its pop-oriented accolades. Both of those records are often ranked among his very best, but Lodger usually falls by the wayside. Its main problem comes from being lodged (heh, lodged) between the colossal "Low" and "Heroes" and immediately followed by the also enormously acclaimed albums "Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)" and "Let’s Dance". Lodger is a subtle album and subtelty can sometimes come off underwhelming. But some 35 years later, it is a considerably more enticing album to flip on than first realized.

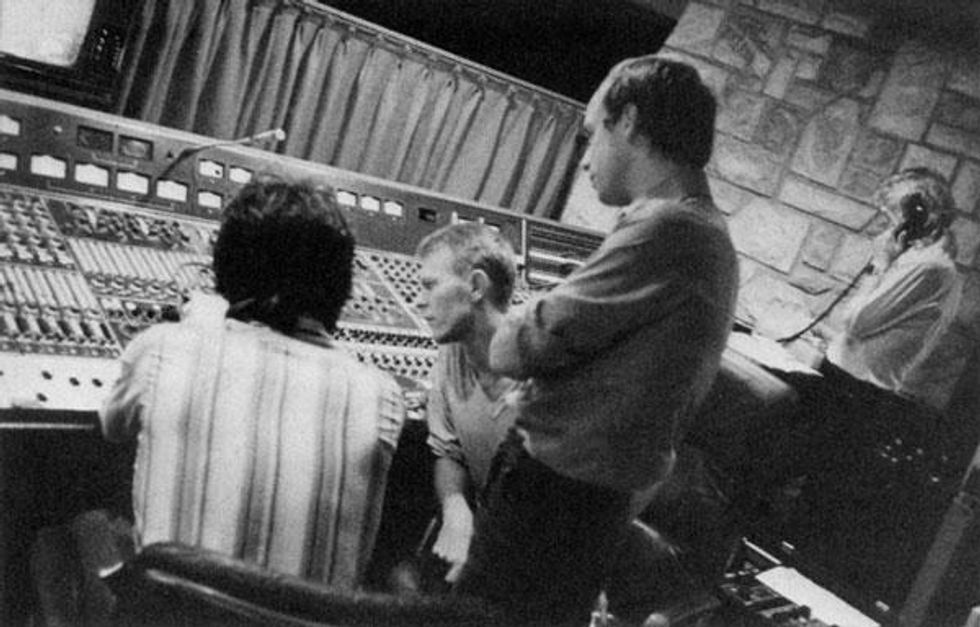

"Lodger" was recorded in two sessions, in between different stretches of tour dates, with the first one taking place in September of 1978 and the second in March of 1979. In an interview 22 years later with UNCUT, Bowie would acknowledge a certain displeasure with the final mixing and recording of the album, due to the disarray of his and producer Tony Visconti's personal lives; however, he also expressed gratitude towards fans, who appreciate the album as they do "Low" and "Heroes" for the ideas that did come through correctly.

During the recording sessions for "Lodger," the quintessential relationship between David Bowie and Brian Eno was reportedly tattered. Eno, and perhaps Bowie as well, were both pragmatists, so the project continued nonetheless. This would, however, be the last collaboration between the two, signaling perhaps the end of the Berlin-era. Some 15 years later, Bowie and Eno would collaborate one last time, on the album "Outside," which, while beloved by fans, was simply not on the same level as the trilogy.

"Lodger" is the shortest of the Berlin Trilogy albums, clocking in at 35 minutes. It is a less experimental record, but by no stretch of the imagination is it a commercial record. It was critically panned upon release, but those reviews have softened in more recent years, as the record is certainly a grower.

While both "Low" and "Heroes" were laid out somewhat fifty-fifty in regards to instrumental and vocal-barring tracks, "Lodger" is composed with a certain absence of ambience. That said, Eno’s influence is still very prominent on the album, electronically and in its production. Overall, the production on the album is pretty impressive, but the musicianship, overwhelmingly so. Between the two of them, Eno and Bowie have 16 musician credits on the album.

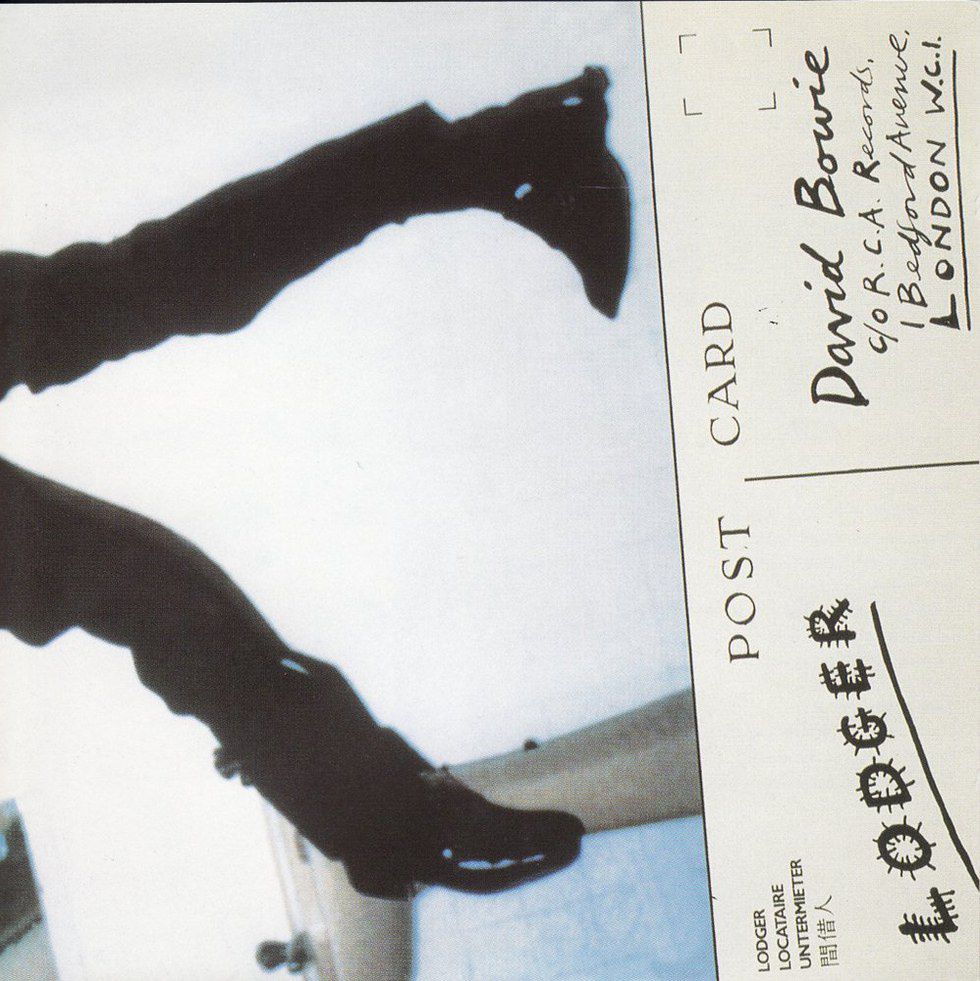

The album's artwork is certainly the strangest of the trilogy. It was photographed by Brian Duffy, in a gritty, blurry, low-quality Polaroid camera. The picture was then spread over the gate-fold, leaving the strange Bowie-feet cover it is now commonly seen with. While some versions of the albums have flipped the image, so Bowie is lying vertically across the front, most have remained loyal to this original version. The album was also devoid of a track list on the outside. The inside of the gate-fold, as shown in this article, features a strange array of images, including the corpse of revolutionary Che Guevara, a Renaissance painting called "Lamentation Over the Dead Christ" by Mantegna and some nice Omega wristwatches.

There were three official singles for "Lodger," but the singles process was a huge headache for RCA. The song "Yassassin" was released as a single, but only in a couple countries, notably Turkey, where its oddities and Turkish style was most appreciated.Other than that, there was "DJ," which is an interesting moment for Bowie, who seems to be imitating the style, somewhat, of David Byrne of the Talking Heads, whom he had recently befriended. This experimentation compliments the song well, but it was a poor choice by RCA to be the second single from the album. It was just too out-there to succeed as a pop single. The much better singles were "Look Back in Anger" and "Boys Keep Swinging."

"Boys Keep Swinging" was the obvious standout single, but RCA was concerned that its very liberal sexual message was too poignant for the still very conservative U.S. market, so "Look Back in Anger" was chosen as the lead-off single for the U.S. instead. The song was very poorly received as a single; most critics called it absolute rubbish. While it is certainly not one of the best songs on the album, it's definitely not a bad single. Though "Boys Keep Swinging" was replaced as a single in the U.S., Bowie did still perform the song on TV, when he appeared with Martin Sheen on Saturday Night Live. And while NBC did choose to censor some of the song's lyrics, they certainly fumbled on censoring the performance entirely, as it featured Bowie performing on stage as a floating head above a puppet body, with a slinky-like comically-caricatured dick popping in and out of his trousers.

The singles are not what are most attractive about "Lodger," of course. As an experimental pop album, it's the weird and zany moments, the deep cuts, that are so quintessential for Berlin-era Bowie and make this album worth visiting again and again. "African Night Flight" and "Red Sails" are some of the best -- just absolutely boggling and great.

The opening track, "Fantastic Voyage," is a lyrical labyrinth; to attempt to decipher it seems very difficult. The title at first seems like an obvious nod to Jules Verne's novel, but it could also be directly speaking autobiographically of his own strange voyage, from Thin White Duke Bowie lost in Los Angeles, to this newer matured, introspective Berlin Bowie. Or indeed, the literal journey from living in one continent to another.

As stated, the reception for "Lodger" was not glorious. Rolling Stone panned it, as did many other elites of the '70s music press. Commercially, it didn’t fair great either, charting poorly and staying charted for a considerably shorter period of time than its forebears, in both the U.K. and the U.S.

But "Lodger" was never an album meant to be a No. 1 smash hit; that would have been missing the tone and atmosphere of the record entirely. In recent years, however, it's become championed by some as a definitive Bowie highlight. Many musicians, notably electronic musician (and future David Bowie next-door neighbor) Moby, have been huge advocates of the album.

The release of "Lodger" and the subsequent promotions led to a bittersweet moment for Bowie, with the start of divorce proceedings with then-wife Angela Barnett after nine years of marriage. Thus, somewhat sanctimoniously, several eras of his life came to a close all at once

1980 (and beyond)

The years that followed started well enough for Bowie. He had huge hits, both monetarily and critically with "Scary Monsters (and Super-Creeps)" and "Let’s Dance." His next albums, "Tonight" and "Never Let Me Down" were successful on the album charts, but critically regarded as very poor. At the end of the '80s, Bowie formed a hard-rock band called Tin Man, which recorded two albums, both of which were received mildly-to-moderately well, but definitely gave him the boost he needed to continue recording his own albums.

The '90s were a great time for Bowie. He recorded "Black Tie White Noise" and "Earthling," both of which, like "Lodger," were superb albums and criminally underrated. The new millennium rang in with a relatively weak Bowie album, "Hours," but this would be followed up by two stronger ones in the next thirteen years, 2002’s "Heathen" and 2004’s "Reality."

Regardless of critical praise for his efforts from 1990 onward, Bowie would not see commercial success in the way he had in the '80s until his final two albums. 2013’s "The Next Day" and this year’s "Blackstar" were both No. 1 in the charts.

The Berlin Trilogy, while important for Bowie, is only one fragment of his large Rubik. The star saw so many defining achievements. In five decades, he released 26 albums, most of which are good, if not great. Some are downright classics. With The Berlin Trilogy, Bowie not only recorded his autobiographical struggles, he encapsulated a moment in time—the late '70s—and with it, what was to strive for in music, predominately electronic music.

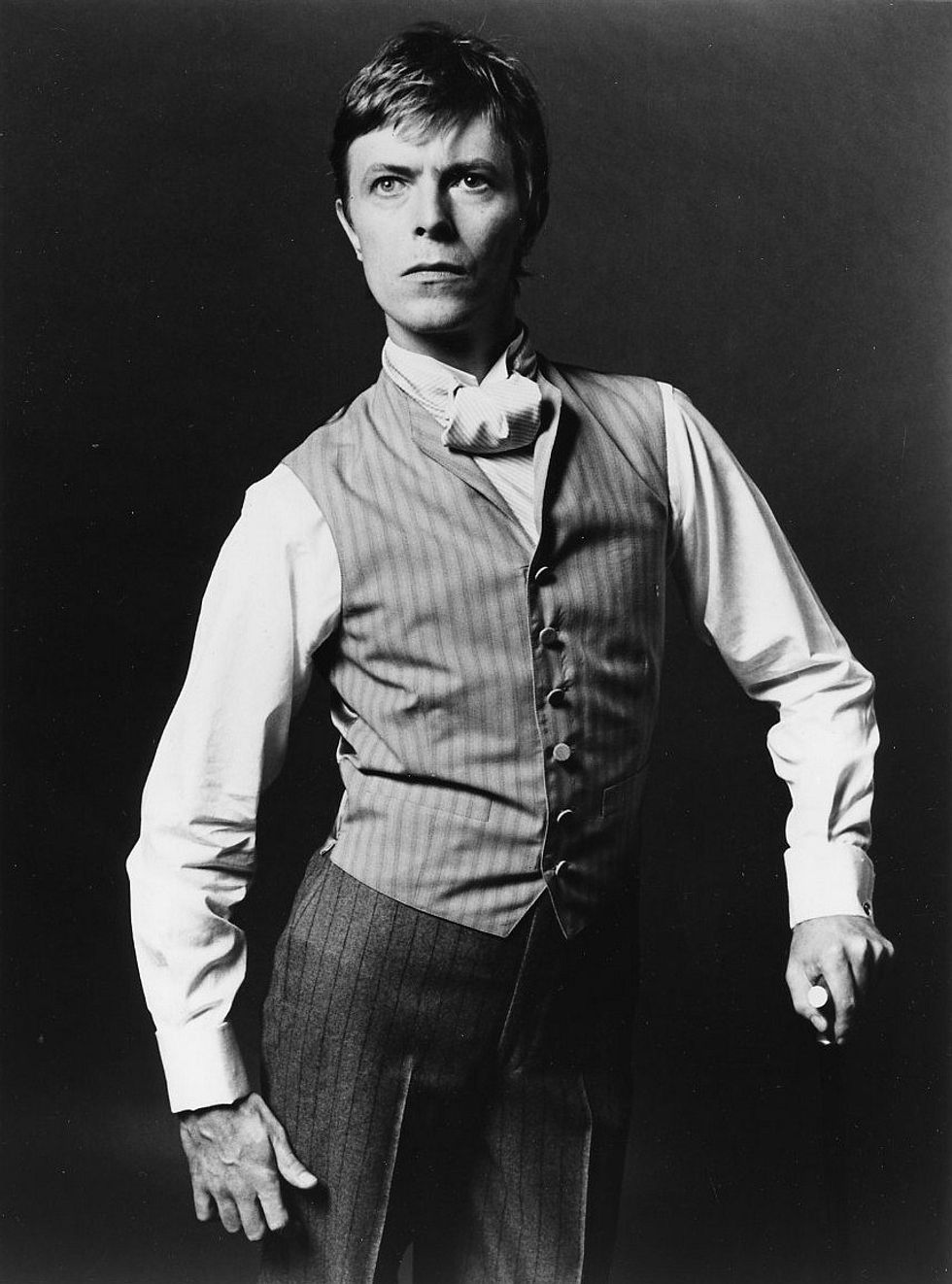

What Bowie did in those years was what he was best known for doing—reinvention. He took himself, exhausted and riddled by pending divorce and cocaine abuse, from the dregs of Los Angeles as the Thin White Duke, to Berlin, and a new era, a bold one. Truly, it was one of the most magnificent periods of his life.