Recently, an article surfaced on the Internet in which a fellow college student, Alyssa Slicko, wrote about why she was against free college tuition. The article was shared thousands of times and received tremendous support. However, the article left me feeling sick to my stomach. Alyssa’s arguments are simply not applicable to the vast majority of students in the country. Here’s why.

This girl—a student at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock—made, as far as I can tell, two main points in her support of college tuition: scholarships are available to students who earn them, and college is a privilege. When researching for this article I found one more argument that many people who are opposed to free tuition use: the availability of student loans.

Argument One: “Student loans are an option.”

The student loans argument goes like this: if someone wants to go to a college they cannot afford, they can just take out loans from various sources and then pay them off later. This is definitely an option, but not a bulletproof one. Loans are a temporary fix for a lasting problem. Students who want to attend an expensive school (and this does not mean a school that is objectively expensive, but rather one that is expensive for that specific person) are most often destined to spend more time working in order to pay for school and to later pay off their debt.

This was the case for my father. While attending Missouri State University, he worked 40 hours a week—the same amount as a full-time job—as a manager of a McDonald’s in order to put himself through school. This meant that he had far less time to study or do extracurriculars. He also often did not have time to take a full course load, meaning his time in college stretched beyond the traditional four years.

His story demonstrates a key fact: student loans may be good in the short term, but can be harmful in the long term. Because my dad didn't want to be saddled with debt, he sacrificed both his free time and his class time to study for work. But let’s say, for the sake of the argument, that he instead did only take out loans and could then study as much as his heart desired. That would have forced him into debt well into the future, meaning he and my mother would not have been able to provide us with the life they desired.

I can predict what Alyssa might say in response to this: that it built character. Indeed it did. But there are other ways to build character, ways that don’t require countless people to work long hours or sink into debt in order to get an education.

Argument Two: “But what about scholarships?”

Luckily for me, I was able to earn enough scholarships to attend college at Truman State University virtually for free. It appears that Alyssa was able to earn scholarships as well. Here’s what she wrote about it:

“I never asked my parents to pay for me to go to college. I made sure that I would study hard to get good enough grades to receive enough scholarships. I decided not to attend the most expensive school in the state, and with working as hard as I did in high school, I should receive a degree in four years, debt free.”

The same is the case for me. I sacrificed going to a more expensive school in order to go to a school for free because of the scholarships available there. And like Alyssa, I worked extremely hard in high school. I took nearly every AP class that was available and got 5’s on every test. I spent hours upon hours doing homework each night. I volunteered upwards of four hours per week. All of this was exhausting—though rewarding—and all of it contributed to the scholarships I received.

However, Alyssa makes a point that destroys her argument. She writes:

“I worked hard throughout high school to get good grades, to get into college, and to get my tuition paid for. That discipline was my first experience of the ‘real world.’ At some point in your life, everything stops getting handed to you. You have to work for the things you want.”

This argument is toxic in its implications. Simply put, it implies that students who do not earn scholarships do not work hard. That is an extremely harmful assumption. Yes, I worked hard to get into college, but that was because I had the time for it. More importantly, that was because I had the money for it.

My parents could afford to live in a well-off suburb with an excellent public school system. My parents could afford to pay for a private ACT tutor, as well as the chance for me to take the ACT and SAT several times until I got the necessary scores. My parents could afford to feed me, clothe me and shelter me. I did not have to worry about those things and could instead focus on school.

My parents could afford to buy me a car so I could drive to volunteering locations, cross country practice and networking events. My parents could afford to send me to various colleges across the midwest several times so I could interview in person for my scholarships. My parents could afford to pay for my private cello lessons, advanced writing camps and social justice leadership groups, all of which enriched me as a person and made me more marketable for scholarships.

Because I was able to afford all of these privileges, the scholarships came easier. I know many students with my same work ethic and passion who do not have the same opportunities. I have tutored and mentored countless students who dream of college but are forced to worry about the present instead of the future—how will they get home after school? Will they get to eat dinner? Will they have access to Wi-Fi in order to do their homework?

These students work extremely hard. I would argue that they work harder than me. Sure, I might have poured myself into preparing for college, but I had the time and money to do so. These students do not.

Alyssa asserts, “At some point in your life, everything stops getting handed to you. You have to work for the things you want.” For her and myself, that time was college, or, more likely, has not even come yet. But I would argue that for the students who do not earn scholarships and cannot afford college without financial aid, that time has come much sooner.

It is simply false to assume that every student in America has had the same privileges as you. Because my family is comfortably middle-class, I was able to afford many advantages that other students cannot, which gave me an edge when applying for college and scholarships.

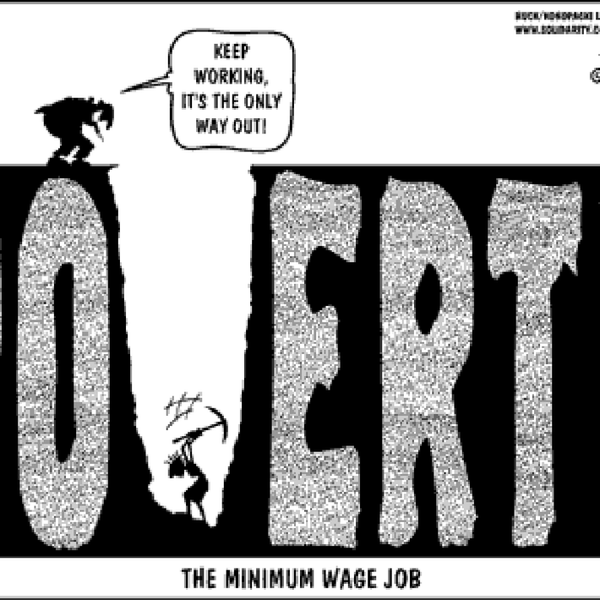

Here is a handy graphic:

On the left, we see "equality." Each child is given the same-sized box in order to see over the fence. However, the different heights mean that two have a full view of the action while one cannot see anything. Contrasting that is "justice," in which the children are given varying amounts of boxes so that each may see the game.

Free college tuition would be like the varying amounts of boxes. As privileged people, Alyssa and I do not need to think about all the little advantages we’ve had that have led up to us being able to afford a college education. But it is essential that we acknowledge it.

Argument Three: “College is a privilege.”

Alyssa’s most central argument is that college is a privilege. But 100 years ago, high school was a privilege; most students ended their education after six or so years in order to work to support their families. And before that, any education whatsoever was a privilege. Only the privileged (i.e., the male equivalent of modern-day Alyssa Slicko and myself) could get any education at all.

Society is constantly changing. For one to obtain a well-paying job, one must usually have a college degree of some kind, especially in this competitive job market where work availabilities are so sparse. High school degrees simply don’t cut it anymore.

Further, while someone without a college education might be able to find some sort of minimum-wage job, one must acknowledge that a minimum wage is not a living wage. Quality of life increases drastically when one gets a college degree.

Alyssa’s mindset—that “college is a privilege”—is revealing of the troubling, deeply-ingrained belief that some are more deserving of opportunities than others. I believe that everybody, no matter the differing opportunities and privileges they have been born with, deserves a shot at college if that’s what they desire.

Being able to pay for college should not be the deciding factor in whether someone goes or not. I am not claiming that free tuition for everybody will be easy. It is, however, necessary.