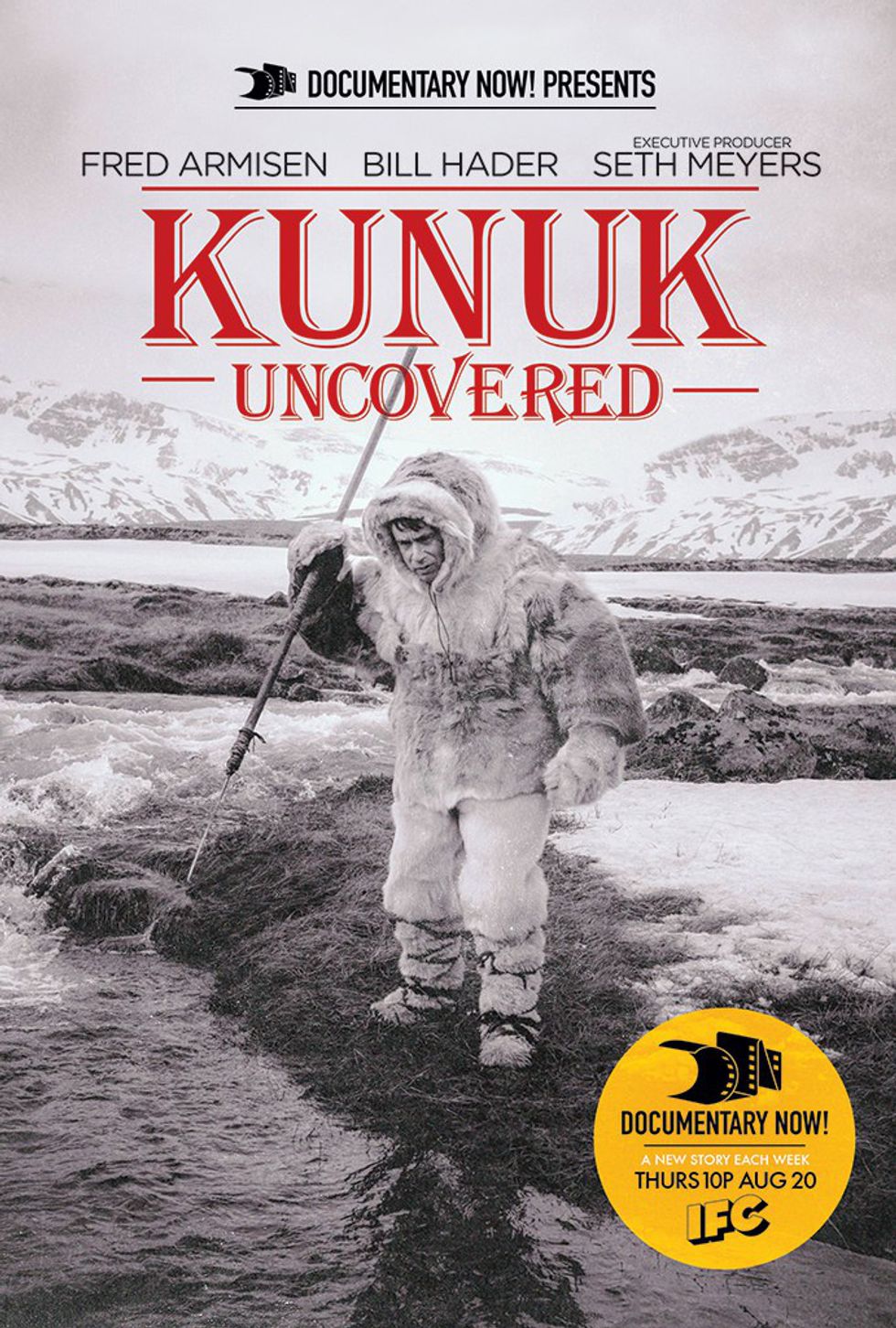

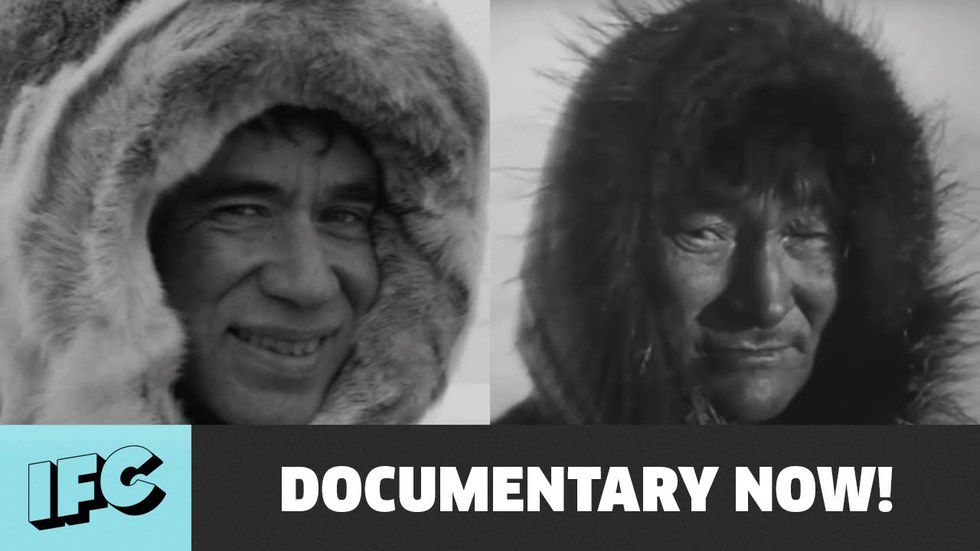

Ridiculous, sophisticated, innovative and fake. All these traits keep me coming back to Documentary Now! (2015-), IFC's clever addition to the mockumentary genre. Helen Mirren hosts this imagined anthology series á la Masterpiece Theatre, supposedly on its 50th season. Each episode presents Fred Armisen and Bill Hader in some outlandish spoof of true, groundbreaking documentaries. Episode 3, Kunuk Uncovered, caught my attention with its hilariously dismal critique on Nanook of the North (1922). Reliving fond memories of my time in Walla Walla University's film department, I knew I had to revisit the facts of Nanook and how the 1920s handled controversial cultural gaps.

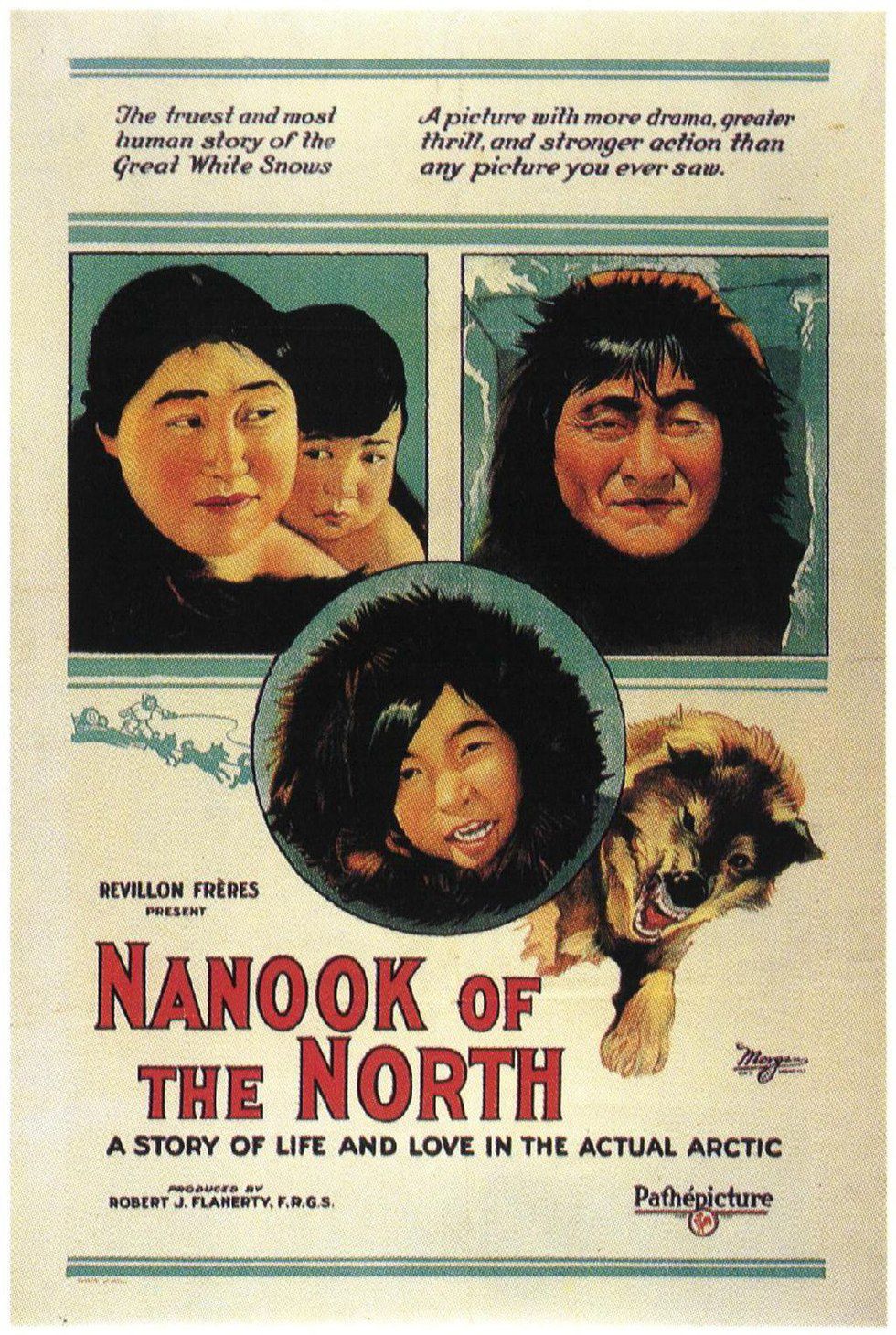

Nanook of the North was seminal in the world of film as (technically) the first feature-length documentary. Director Robert Flaherty spent sixteen months in the Canadian Arctic to get personally involved with his subjects. Nanook and his family were chosen to be the central subjects of the film, and Flaherty documented their way of life.

The Eskimos were flattered by Flaherty, who showed genuine interest in their lives. He shared his technology with them, such as a phonograph, photographs and footage of the film. Nanook took a liking to the phonograph and tried to eat one of the records. When the Eskimos saw photographs of themselves, they didn’t know which way to hold them. They had only seen their reflections in water before. Seeing footage of themselves in the film (which was screened in a post office) excited the Eskimos so much that they demanded to see it again on several occasions.

After Flaherty returned home, Paramount saw the footage and decided that it was not marketable. In 1922, Pathé Pictures struck gold when they released it to critical and commercial success.

With Nanook of the North, Flaherty created the narrative nonfiction genre. In Turning Points in Film History, film historian Andrew J. Rausch said that Flaherty's purpose was to capture the attention of those who would otherwise have no “scientific interest in the lives of primitive people."

Flaherty was criticized for structuring certain scenes and for getting too involved with his subjects, supposedly making the film unrealistic and disqualifying it as a documentary. Flaherty was involved in many aspects of the filming. He told the Eskimos how to hold their spears and when to throw. He had them build a special igloo because normal ones were too small for filming inside. As well producing, writing and directing the film, Flaherty arranged the shots (and his subjects) just the way he wanted them. This was to tell a story, as well as represent how Nanook and his family actually lived. Panthé, however, was not concerned with what kind of a film it was. It was a big success! So they hired Flaherty to direct another film, Moana; this one being about the Samoan culture. Unfortunately, Moana did not see such public interest.

Flaherty would be forever remembered for his culture-crossing production, while two years after filming, Nanook died of starvation while on a hunt.