Creeped out?

What turns us off about poor Tom Hanks? A talented actor plays an altogether friendly train conductor, yet in that digitally processed face lingers an inescapable sense of horror.

The term "uncanny" describes something strangely familiar that inspires strong negative emotions.Though early German psychologist Ernst Jentsch pioneered the idea, it gained fame from psychology’s resident expert on creepy things, Sigmund Freud. His idea was that something uncanny, especially representations of people, cause an internal conflict: their familiar characteristics attract people, but their incongruity cause confusion. Though there are differing opinions as to why this is (Freud brought it back to the Oedipus complex, naturally), but the result is an overwhelming feeling of, well, creepiness.

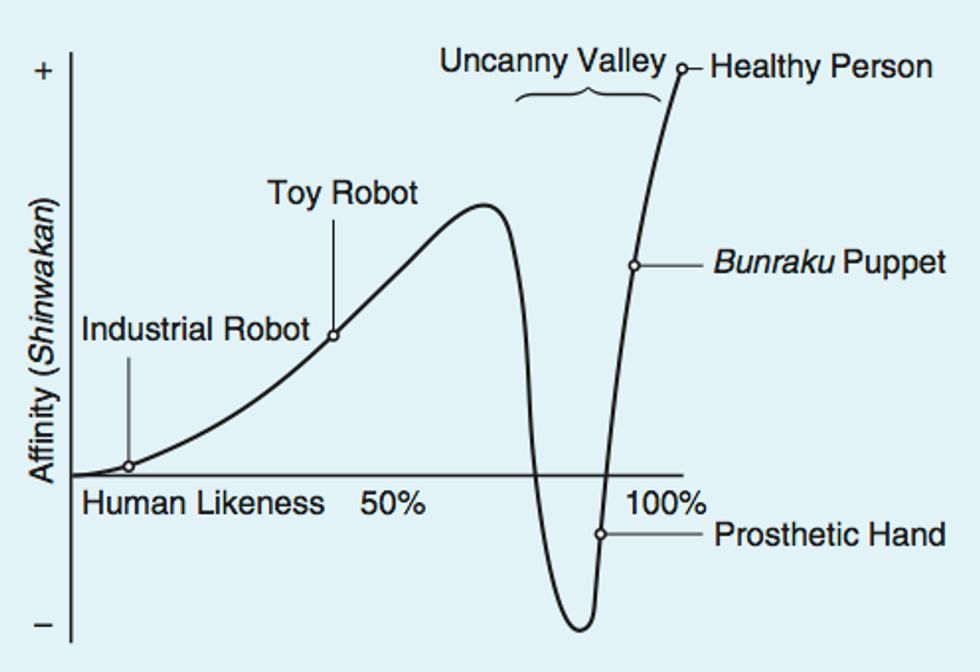

A representation of this theory is "The Uncanny Valley," named for the trough of a graph where the creepiest of human creations reside, according to Masahiro Mori and "The Uncanny Valley."

The space between an object and a living being is where the creepiness is most distinct. When something that brings pleasure or simplifies our lives, like a fantasy film, comes too close to real life, it creates a conflict between the world where the viewer desires to dwell and the world they are leaving; therein lies the horror.

Likely as not, people didn’t consciously think these thoughts while watching "The Polar Express." They may have thought, as critics did, that an attempt at realism in animation caused a less-than-cheerful holiday experience. A well-intentioned movie was discounted based on its appearance.

In the end, all art is uncanny: it may come close to reality, in image or plot, but no work is exact in its portrayal. In fact, as seen in "The Polar Express," attempting to be too real ruined the illusion of the film and the reality it created (as much reality as there is in a film about Santa Claus, anyway).

It’s relevant to observe this effect in everyday life, especially for adolescents, for whom appearance is invariably entwined with personal identity. The appearances we create, and how we interpret those of others, reflect a world we create for ourselves, or a world from which we look to escape.

But what does it take for our subconscious knowledge of what is human to be defied? When does appearance represent the whole truth of a person, as a painting can be judged on the pleasure of its subject, rather than what it stands for?

And when does it cross the valley to become sub-human?