In individualistic cultures, we are often told when we create not to be afraid of a blank page. The page, the stage, the canvas has potential; we should chase whatever we are feeling and create such that this sensibility is fully articulated. There is certainly merit to this idea, not only because unfettered creation is good for the soul, but because if we devote our consciousness solely to the burdens that might befall a work rather than to the natural creative processes taking place, that natural production will be halted. That is to say that artists must indeed function with a sense of freedom, and it is in part this freedom to express ourselves that draws us to creativity in the first place.

A historic example of such completely unfettered creation is the work of poet Sylvia Plath. Born in 1932, she was a major forerunner of the unreservedly emotional and often autobiographical genre of poetry that arose in America the 1950s and 60s known as confessional poetry. Like many of her fellow confessional poets, Plath delved into intimate subject matter that had yet to have been discussed in American poetry, such as personal brushes with death, mental illness, and trauma. Her work is important in the freeness of its emotion and the deliberateness with which she converts personal trauma into the public offense, attempting to convey the great magnitude of her suffering.

However, in one of her most famous poems, "Daddy," the way she goes about emphasizing the magnitude of her pain with regard to her troubled relationship with her cold and removed father is by conflating it with Jewish internment and genocide during World War II. "I thought every German was you. And the language obscene an engine, an engine chuffing me off like a Jew."

What happens when we create utterly free of restriction? Yes, Sylvia Plath had some degree of emotional freedom in being able to write what she did and use the analogies she did; as a poet who suffered from severe depression and survived an attempted suicide before successfully taking her own life twelve years later at the age of 31, the rawness of her writing likely helped fortify her against the heavy burdens she faced throughout her life. But when we create without considering the potential repercussions of our creations, we can perpetuate negative creative practices and societal conditions. We can create something culturally insensitive and belittling, something under-representative and narrow-minded.

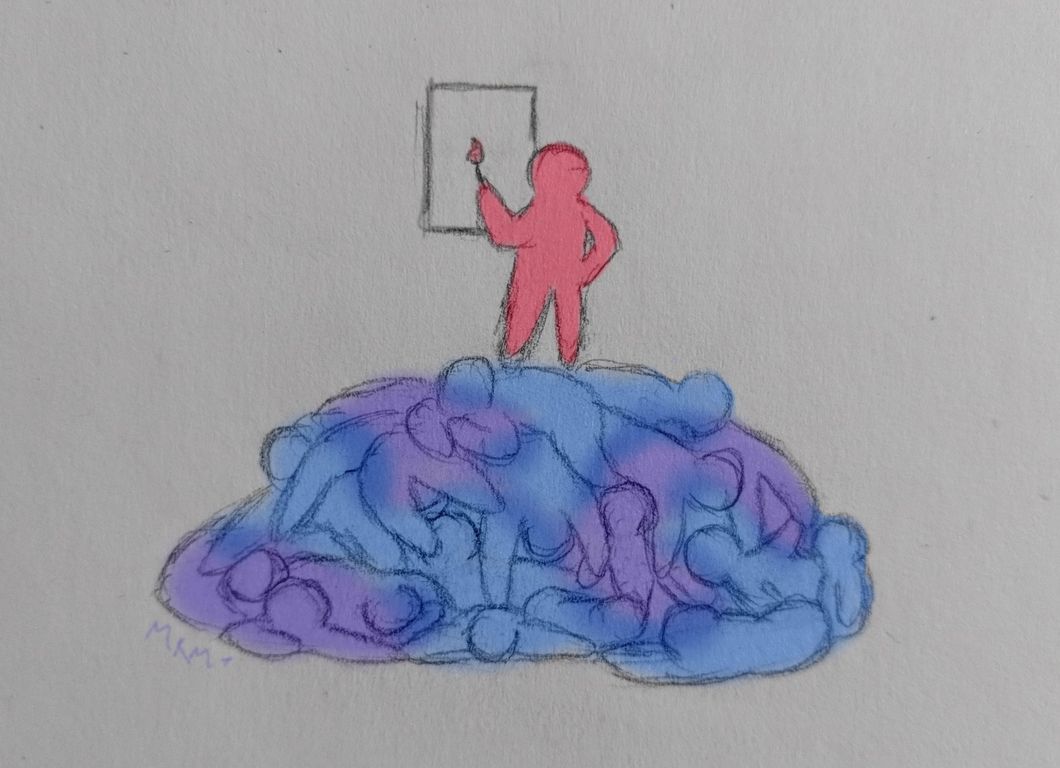

It is a comfortable idea that the creator, who is poised only to benefit and never to be hurt by his/her/their own work, does not owe anyone anything and has no responsibility in the creative process, except perhaps a responsibility to the execution of the work itself, or to the literary experience of the reader in mind. And indeed there is value to the idea of chasing those fleeting ideas and seeing a challenging notion through. But as much as we would like to create without care, the truth is that if a creative work will one day enter a public space, then there is no way its creator can be without responsibility. Nothing we create is insulated from society but rather by virtue of existing and being shared becomes a part of the world around it; everything interacts with that larger world and the people within.

That is to say, countless movies about only certain types of characters interact and impress upon all who do not fit within these narrow categories that they are somehow "other," that they are somehow less valid and less worthy of examination and glamorization. That is to say that an analogy that conflates personal suffering with the senseless slaughter of a race of people impresses upon victims and survivors that their heritage is fair game for exoticism and metaphor. That is to say that a children's story about a certain kid and not another, however innocuous on the surface-level, makes a statement about whose lives and problems carry more weight and deserve to be discussed. That is to say that indelicate and ill-thought-out work, churned out by a creator who, when the time comes to publish work, chooses to be self-indulgent rather than sensitive and aware, has reverberations greater than the individual.

It is disturbing to think that an artist would not be conscious of this reality, of the effects a work can have once released, of the implicit and often unintentional statements it makes. The sharing of art can be an utterly carefree practice. It often is made to be by its practitioners. But it certainly shouldn't be.

man running in forestPhoto by

man running in forestPhoto by

"I thought you knew what you signed up for."

"I thought you knew what you signed up for." man and woman in bathtub

Photo by

man and woman in bathtub

Photo by  four women sitting on black steel bench during daytime

Photo by

four women sitting on black steel bench during daytime

Photo by  Uber app ready to ride on a smartphone.

Photo by

Uber app ready to ride on a smartphone.

Photo by  woman in red tank top and blue denim shorts standing beside woman in black tank top

Photo by

woman in red tank top and blue denim shorts standing beside woman in black tank top

Photo by  blue marker on white printer paper

Photo by

blue marker on white printer paper

Photo by  welcome signage on focus photography

Photo by

welcome signage on focus photography

Photo by  woman in white and black striped long sleeve shirt lying on bed

Photo by

woman in white and black striped long sleeve shirt lying on bed

Photo by  pink pig coin bank on brown wooden table

Photo by

pink pig coin bank on brown wooden table

Photo by  person holding iPhone 6 turned on

Photo by

person holding iPhone 6 turned on

Photo by  person holding pencil near laptop computer

Photo by

person holding pencil near laptop computer

Photo by  person slicing vegetable

Photo by

person slicing vegetable

Photo by