My sister and I used to take walks in a prairie behind the library in my hometown. One day, we came to the prairie, and my sister gasped. The prairie was scorched, black and sooty like the hearth of a fireplace. Because there was no lingering smoke, no faintly glowing coals, no recent indication of a fire, the blackness felt eerie. “I bet some dumb kids were out here playing with fire,” I said, shaking my head. I remember looking online for news of a fire but found none.

It was a while before I realized what had happened was a prescribed prairie burn—a land management tool to improve the health of a grassland. Prairie management specialists diagnose prairies with poor health judging by overcrowding and a build-up of flammable material, then prescribe a controlled, closely watched fire to the prairie.

Although the immediate effects of fire look dreary and disastrous, controlled burns recycle nutrients back into the soil, minimize the risk of calamitous wildfires, manage pests, invasive species, and disease, and promote the growth of natural prairie flowers, trees, and grass.

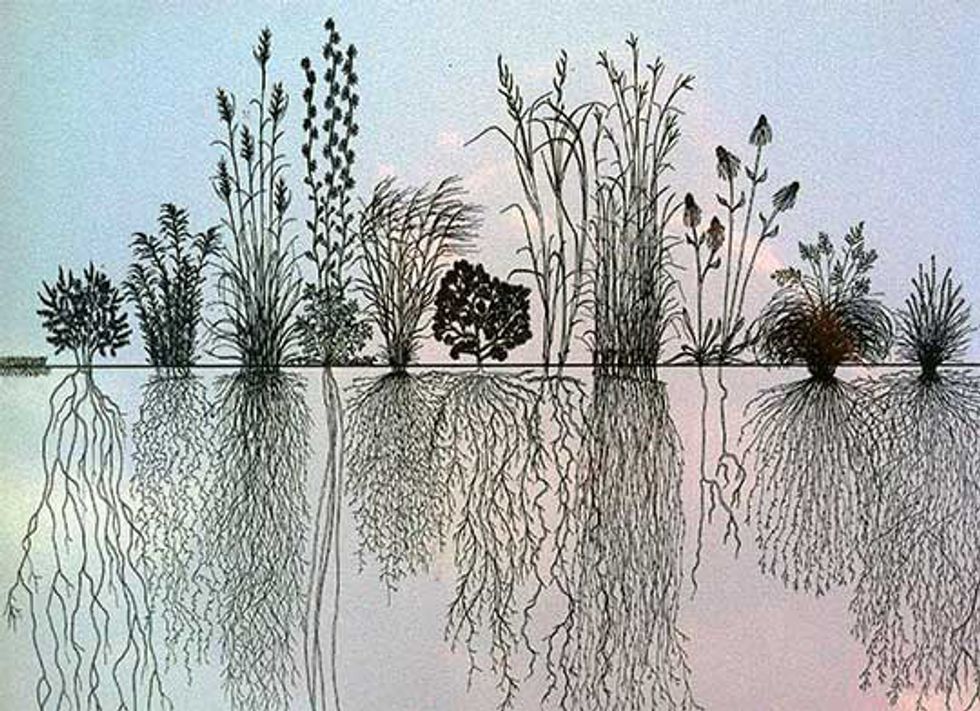

Plants that grow naturally in prairie ecosystems have long roots that run deep into the ground. That means the plants that are supposed to be there will regenerate quickly in the event of a controlled burn. In less than a week, a previously blackened and desolate prairie may be flushed with new life.

But before there were land management and restoration specialists, there was the first, the original specialists—indigenous tribes.

There is a myth that goes something like this: When Old World pioneers came to America, the land was pristine and untended. The Native Americans lived primitively with the land, too uneducated or too unwilling to manage it and reap its benefits.

This myth demonstrates an ignorant presumption on the part of early settlers since it contains no truthfulness. In fact, Native Americans were so advanced in land management skills that our modern management practices today are directly based on what was done by Native tribes for hundreds of years, including controlled burns.

While Native Americans were carefully using fire to nourish, diversify, and protect the land, the advantage of fire for the health of a prairie, or for the prevention of a wildfire, was mostly unbeknownst to the American settler. This unawareness continued well into the 20th century—U.S. Federal Land Management Policy demanded all fire to be considered harmful, and thus planted a relentless undertaking of complete fire suppression.

Change began to take place with the famed Aldo Leopold, the father of American wildlife management, encouraged the adoption of Native American environmental knowledge. But it wasn’t; Aldo Leopold had died, so his son A. Starker Leopold wrote a series of land management recommendations (known as the Leopold Report) for the Department of Interior that the federal government recognized the ecological benefits of controlled fire. Finally the Wilderness Act of 1964 officially allowed for the use of controlled burns to manage federal land.

Last spring, I came across a prairie bejeweled with black, thin ash and a layer of charred vegetation. I didn’t gasp, or mourn the loss of a prairie, or think about checkin the news for an accidental fire. I surveyed the scene and went home. Then, the following week I returned to the exact spot that had just been monochrome with blackness and saw green shoots had pushed their way through the ash. The prairie was healing, coming back stronger than before, and I was pretty sure ‘playing with fire’ had nothing to do with it.