Computers. An integral and indispensable aspect of our lives. I'm writing about computers using a computer. They're in our cellphones, calculators and watches. Tracing its ancestry, however, is equally fascinating as tracing its future. We're all familiar with Charles Babbage and Alan Turing, Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, the old and new gods of the golden age of technological progress that almost seems to define, for some people, the turn of the new millennium. This article will look at how we started down this path, where we are, and where we are all collectively heading, using art and health as a focal point to pin down both advantages and disadvantages of technology, gadgetry and machines becoming increasingly essential parts of our lives.

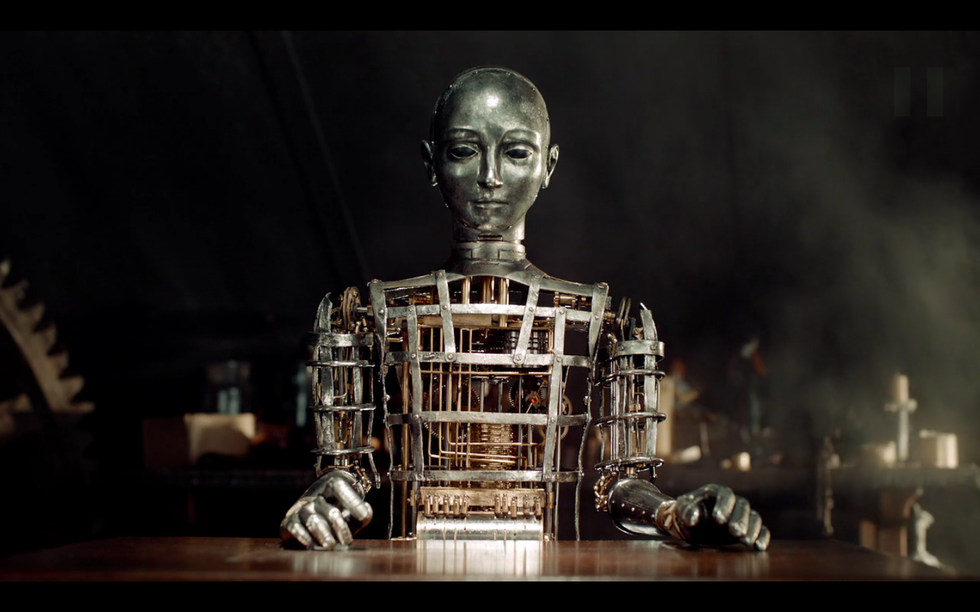

The most obscure ancestors of the computer are probably the Jaquet-Droz Automates, a trio of doll automata constructed between 1768 and 1774, known as the 'musician', the 'draughtsman' and 'the writer.' (Descriptions taken from Wikipedia).

The musician is a female organ player. The doll is actually playing a genuine (yet custom-built) instrument by pressing the keys with her fingers. She "breathes" (the movements of the chest can be seen) and follows her fingers with her head and eyes. The draughtsman is the red haired child on one side of the musician. It can draw four images: a portrait of Louis XV, a royal couple (Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI ), a dog with "Mon toutou" ("my doggy") written beside it, and a scene of Cupid driving a chariot pulled by a butterfly.The draughtsman works by using a system of cams which code the movements of the hand in two dimensions, plus one to lift the pencil. The writer is the most intricate of the three automata. It employs a system identical to the one used for the draughtsman for each letter, he is able to write any custom text up to 40 letters long (the text is rarely changed). The text is coded on a wheel where characters are selected one by one. He uses a goose feather to write, which he inks from time to time, including a shake of the wrist to prevent ink from spilling. His eyes follow the text being written, and the head moves when he takes some ink.

These automata inspired a frame in the movie Hugo, directed by Martin Scorcese, which follows the adventures of a watchmaker's son living in Paris. It was a book adaptation of a novel called The Invention Of Hugo Cabret. The singular frame defines the whole movie, making it look at once human and likable, but also cold, mechanical and dangerous. The human likeness of the face of the automaton creates this feeling. It is obvious in the movie where this came from. It's a friendly and uplifting take on machines in our lives

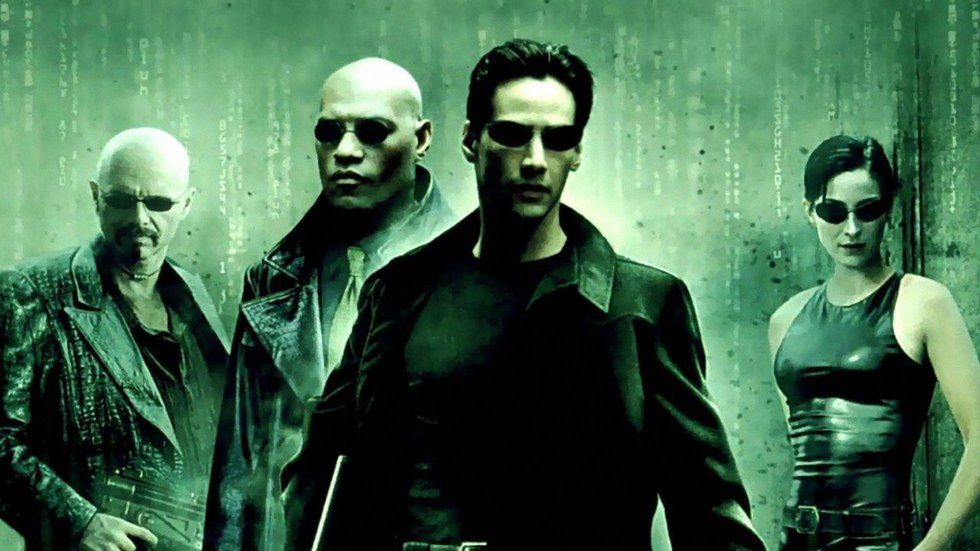

A different type of movie that deals with machines involved in the human experience is the 1999 science-fiction, Kung Fu, action movie called The Matrix. It looks at it differently, offering the scenario that our entire reality is a computer program while our organism state is being used as a collective fuel cell for the machine race. Although it came out before Hugo did, it became a cult movie due to the storyline and the mind-boggling visual effects it employed, which were way ahead of industry standard at the time. It took a grim perspective of machines completely in control, so much so that we were blind to it until we were pulled out of the reality they were keeping us in.

Movies may be well and good for speculative purposes, but real leaps are being made when it comes to machines improving our lifestyles. We are all familiar with iPhones and other such devices, but in the field of healthcare, neural implants, pacemakers with chips in them and insulin pumps that are now networked are examples of the same. Neural implants are being used in soldiers with post traumatic stress disorder as well as elderly patients of Parkinson's disease. While in both scenarios the onset of the disease cannot be stopped or reversed, they have been extremely effective in reducing their extent, so that people affected by it may lead lives that are closer to normal.

The risk of one of these devices being hacked by a third party, however, are as real as the help these devices provide the patients. This is an uneasy segue into another problem with using technology to solve problems - drone strikes and technological warfare. Can a remote really be used to justify the ethics of long range retaliation in battle? Does long range weaponry reduce the moral cost on either side, or increase it? And if a country's defense networks are indeed networked, could a hacker on the other side of the world bring the country to a standstill? These are questions that need to be considered as we rush into the golden age of technology and where it may take us.

The peril of technology is indeed similar to one faced by two great scientists of the previous century - Werner Heisenberg and Robert Oppenheimer. Heisenberg managed to split the uranium atom and Oppenheimer managed to synthesize an atomic bomb, helping the United States decidedly win World War II. However, in the remainder of their days once the war had concluded, Heisenberg became an unintentional figurehead for peaceful science, whereas Oppenheimer, the man who succeeded, was ostracized by the academic community. Maybe the next great inventors will be subject to a similar dilemma within their lifetimes and the lifetimes of their inventions - but only time will tell.