A straight “A” student, gymnast and half-marathon runner, Christa Quattromani (pictured below) expected her high school career to be smooth sailing. But she also wanted to party, so the summer before her freshman year, Quattromani tried drinking for the first time – and it was a life-changing experience that led to several waves of drug addiction.

Attending the University of Pennsylvania, an Ivy-league school, Quattromani still managed to remain academically successful and eventually recovered from her cocaine addiction.

However, one day she broke her finger and the doctor prescribed painkillers, beginning another up-hill battle of addiction

Quattromani relapsed, became addicted to heroin and overdosed on an Amtrak train.

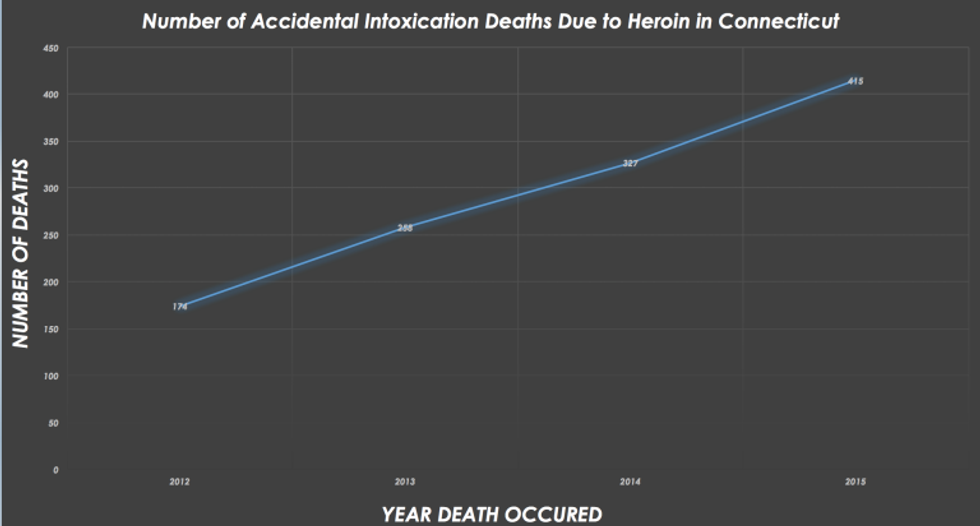

Luckily Quattromani was saved with Narcan, an antidote to heroin and similar drugs. But that’s not the case for 415 others who lost their battle with heroin in Connecticut last year, according to the Connecticut Office of the Chief Medical Examiner.

A “Public Health Problem”

Connecticut had nearly a 128 percent increase from 2012 to 2015 in heroin, morphine and/or codeine related overdoses. Some 195 people died in 2012 from these types of drug-overdoses, skyrocketing to 444 deaths in 2015.

Pictured above: Graph demonstrating the increasing death toll from heroin in Connecticut. Data collected from Office of the Chief Medical Examiner.

Gov. Dannel P. Malloy considers the heroin crisis not just an epidemic or a drug-related crime, but a “public health problem,” according to CT.gov.

Where is this problem stemming from?

Three reasons are behind it: painkiller addictions, a significant decrease in the cost of drugs and a lack of treatment-recovery support, according to Kelley Edwards, (pictured) a coordinator at Partners in Community of Clinton (PiC), a local drug-free and healthy community activist group.

Four out of five heroin users start by developing an addiction to prescription painkillers, according to CT.gov.

Primarily, opioids, also known as prescription painkillers, are the root cause that leads to heroin addiction, Edwards said.

This can be attributed to the over-prescribing of painkillers by medical professionals, Edwards said.

In Connecticut, 72-82 percent of its residents were prescribed a painkiller prescription, according to the Center for Disease Control (CDC).

Essentially the problem is that doctors have over-prescribed painkillers, put them into the wrong hands and not monitored the users, lending itself to the epidemic of painkillers and heroin addictions Connecticut is facing now, Edwards charged.

Despite the accusations that professionals in the drug abuse prevention field have claimed, those in the medical profession and the state government have made an active effort to rectify this issue.

Dr. David Chen, a dentist at the University of Connecticut Health campus in Farmington, said he acknowledged that some of the painkiller addictions stem from some—not all—doctors’ poor prescription management.

“Different doctors prescribe painkillers differently—there is no exact way to do it,” Chen said.

There are a variety of beliefs and styles on how to combat pain, which can make it difficult for doctors when it comes to writing prescriptions for different types of patients, Chen said.

“However, when I can, I always opt for the least addictive drug. For example, I usually push for my patients to try Tylenol or some other over-the-counter pain remedy first, rather than just simply given them a painkiller,” he said.

This philosophy should be encouraged more universally, to avoid future problems, Chen said.

“Because of the current state we are in with addictions, we (doctors) are more careful, conscious and conservative when prescribing potentially addictive pills,” Chen said.

Also encouraging change for the heroin epidemic is the state government.

Since 2008, Connecticut has had a prescription monitoring program in place (called CPMRS: Connecticut prescription monitoring and reporting system). The system is mainly used to keep records of controlled substances, such as addictive drugs like painkillers, to prevent patients from ending up with too much of one drug, according to CT.gov.

Edwards noted that up until 2015, doctors were not required to check the system prior to writing a patient a new prescription.

Now, doctors prescribing longer than a three-day prescription of controlled substances are required to check the CPMRS, according to the new state law.

Also, those receiving prolonged treatment from a controlled substance have to visit the doctor every 90 days.

The surplus of pills left over after the patient is done actually using the drug for its intended purpose is the real problem, Edwards said.

Connecticut has also made an effort to combat the surplus-pill problem by providing grants to local initiatives, such as PiC, to have medication take-back days and install locked medication disposal boxes in facilities such as police departments, according to Edwards and CT.gov. These are designed to retrieve any left-over drugs and dispense of them properly, she said.

As of February 2016, Walgreens Pharmacy also announced it will install “safe medication disposal kiosks (at all of its Connecticut locations) to ensure medications are not accidentally used or intentionally misused by someone else,” according to a company press release. These kiosks will allow any customer to drop-off and get rid of any old medicine, Walgreens wrote.

Also part of the growing problem is that the cost of heroin has significantly decreased, Edwards said. In fact, the cost has decreased 90 percent, according to both the state and federal statistics.

“Years ago it was over $50 a bag with only a few dealers. Today, it is being sold for $5 a hit by many dealers,” Edwards said.

A “hit” is about .1 grams-worth, according to heroin.net.

“Heroin is so cheap—and they’re making a killing on it. Up in Hartford, it’s ridiculously cheap according to the state narcotics police. Dealers go up and buy it for $5, then resell it for $15-20 here (the shoreline),” Edwards said.

Although heroin is cheaper and more accessible, dealers have also changed, said Lt. John Barone, detective commander for the Groton police department, during a community forum on the heroin epidemic.

Pictured above: A forum gathers at Robert E. Fitch High School in Groton to discuss the epidemic.

Those “who are distributing and selling, they are the manipulators. The users are being manipulated by them. They are praying on people who are vulnerable,” said Barone.

Barone also noted that dealers are looking at heroin as a business, looking to make a profit, and not as an addictive drug.

However, some say there’s not enough support for those who became vulnerable.

Meagan E. Seacor, Community Relations Manager for the Stonington Institute, a rehabilitation center, noted that Malloy plans to cut $16 million in mental heath and addiction services funding, even though the governor considers this an epidemic.

Professionals in the field are encouraging him not to do that, Seacor said.

Turning to the care available, professionals say they are offering impactful treatment services to help addicts.

Thomas M. Greaney, a licensed drug, and alcohol abuse counselor, argued it is important to assist addicts with “healing and growing” beyond the life as an addict.

“It’s a matter of not getting high, but getting sick. It’s a disease. They’re not bad people, they’re sick people, desperately wanting to get well,” Greaney said, as he argued for greater access to counseling services for addicts.

Combatting The Epidemic with Narcan

Although some say there has been trouble combatting the problem, some progress has been made, according to others.

For the past five years, Connecticut has kept the heroin epidemic on the legislation table. In particular, one of the focuses has been increasing accessibility to Narcan (pictured below), the life-saving antidote to opioids.

Recent legislation allows certified medical prescribers, including specially-certified pharmacists, to prescribe Narcan to any addict, friend or family member who might be around the user in case of an overdose, according to CT.gov.

A heroin overdose causes opioid receptors on the cells in the respiratory system, responsible for breathing, to fill up. The receptors become blocked, decreasing a person’s ability to breathe, Edwards said.

“Narcan immediately opens up these cells and allows respiration to begin again. The result is an immediate, dramatic change,” Edwards said.

In the past, insurance companies were refusing to pay for Narcan, Edwards said. “Why would they pay for a user (an addict)? Death is a lot cheaper,” Edwards said.

But, during the February 2016 legislative-session, the body’s Committee on Public Health said effective Jan. 1, 2017, no individual or group health insurance policy shall require prior authorization for Narcan or any similarly acting drug.

The legislation now allows users more immediate access to the drug antidote.

Beyond Just Legislation & Antidotes

Legislation and antidotes aren’t everything; education is important too, say authorities.

“In order to address the epidemic, we need a three prong approach: starting with awareness and education (and) trying to spread the word beforehand that this is dangerous,” Barone said.

Other experts agree.

“We need to host local forums and get it into the newspaper that this is a serious issue,” Edwards said. She also suggested drop-boxes for excess pills, to be aware of what’s going on with loved ones and longer rehab programs.

Some like Quattromani had the opportunity to move past her addictions. She now works actively to fight the heroin epidemic and speaks frequently at community forums.

“I am here to shine a light on heroin,” Quattromani said