Despite what the mainstream media would have you believe, it is in fact possible to compare apples to oranges, as this study conducted by a NASA scientist will show you. As with many things in life, there is more than meets the eye, and we will have to delve into the core/pith of what apples and oranges stand for before we can truly compare them.

If you’ve never looked up etymology of Latin-based English words on the internet (although if you haven’t I’m not sure how you’re spending your Friday nights) you may be surprised to realize how much of the English language results from an inability to pronounce Arabic words. In short, when traders brought “naranga-s” from Asia to Europe we called them “orange” trees. The brightly colored citrus fruits were then called fruits of this orange tree. Makes sense, right?

As humans, we have historically had a knack for giving things descriptive names. For example, “Sahara Desert” translates to “The Great Desert Desert” and the Dead Sea describes a sea where nothing can live. (We still do this today) In fact, we only seem to waver on this point where money is involved (think of the naming choices of Greenland and Iceland, or Vitamin Water), but I digress.

Once upon a time, there were pine trees, and the brown prickly things that fell from these were called fruits of the pine tree, pine fruits, if you will. This was a good name and generally accepted until English-speakers ventured to the New World and found something else that was both pine-ier and fruitier which also came from a tree. They decided this was most deserving of the title pine fruit and began calling the other one a pine cone, as it was noticeably more conical to avoid confusion.

A pine cone:

A pine fruit:

The pine fruit, you may recognize as a pineapple. From its conception in the Middle Ages through the 17th century, the word apple was synonymous with any and all fruit. Cucumbers, among melons and other vegetables, were called “earth-apples.” The story of the Garden of Eden contains an apple as a placeholder for any fruit. Even to this day, in French, potato is translated as “pomme de terre” meaning “apple of the earth,” while the meaning of "apple" has come to refer specifically to the most generic fruit, the apple.

16th Century Apples:

An orange by any other name is just an apple.

Over time as cultivation limited the genetic expressions and once exotic fruits became staples, names were shortened or created to accommodate their more frequent use. All of the earth-apples got cool new individual names, while the "apple of the orange tree" was shortened to "orange." What differentiates the two is that an apple is a broad category, whereas an orange is a specific type of apple. Moreover, is it not only a type of apple called an orange, but it also is orange.

Now there is no problem with a fruit that bears its color's name. But surely they had to have had a name to describe orange things before the fruit came to Europe around the 13th century. Though that argument is not infallible, in this case it proves correct. The previous color for orange was called ġeolurēad, and pronounced “yellow-red.” Orange was literally called yellow red. Needless to say, it was a simpler time.

Perhaps this is one of the largest cover-ups in the history of the English language. We have collectively forgotten its existence for 400 years and it explains why no one wants you to dig into the comparisons of apples and oranges. Maybe it stems from a fear of change. If ġeolurēad reentered our vocabulary, might we be tempted to re-name green blue-yellow and purple red-blue? Think of all the financial and sociological repercussions of such an abrupt change (There would probably be little political fallout as red, white, and blue would remain unaltered). Worry not, because luckily for us, science can support orange.

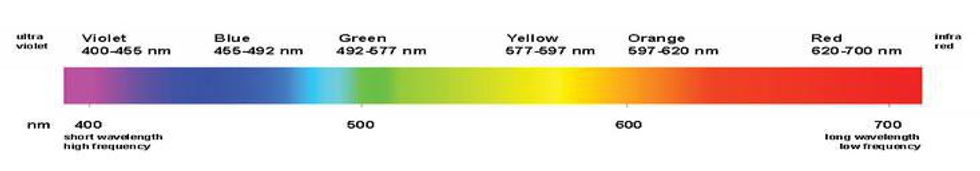

If we think of color not as pigment, but as light, we can assign names to different ranges wavelengths. Stay with me here. “Orange” describes the wavelengths between 590-620nm. To call that yellow red would be to say “the range between but excluding 570-750nm inclusive of 590-620nm.” Confusing? Exactly.

In other words, it would be like only referring to the number 7 as “the integers from 6 to 8, but excluding both 6 and 8.” We could do that, but if we label half of the color spectrum after one phrase, it kind of defeats the purpose of labeling it at all. Also, it sounds prettier to give something a name rather than call it after its base components, which is why we don’t refer to colors by their wavelength/frequency in common conversation, why “water” is used more than “dihydrogen monoxide,” and the term “human” used more than “emotional sack of water, carbon and some other stuff.”

Orange is large, it contains multitudes.

We could open any 16+ count box of Crayola crayons and find that orange has an extended range between the primary colors of red and yellow, green between yellow and blue, and violet between blue and red. Though these are mixed pigments, they reflect the associations of the color spectrum and color found in nature. Though the secondary colors bridge the gaps between the primaries, no one defines the color of grass as the mixture of the sky and marigolds, but as green. Neither is the color of amethyst considered the amalgamation of red of rubies and blue of sapphires but as violet.

Orange can be recreated by mixing red and yellow, but it is the color of flowers in vibrant hues and dusty browns, of fire and sunsets, of fruits and canyon walls which define it. It is both a clockwork and the new black. It was chance that the word orange was taken from the fruit to name the color and gained popularity as English literacy increased and the language standardized, but for the sake of poetry, I officially declare it was inevitable, fate even. By using a word separate from red, yellow, and apple, we are able to expand the associations and the concept of orange.

While at their origin, apples described the world of fruits, including oranges, in recent years that association has narrowed to one type of fruit and tree. The tables have turned; Oranges, once relegated only to one type of tree, can now can describe the world.

Sources:

http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=orange

http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=apple

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight.

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight. Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage.

Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage. Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots.

Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots. Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.

Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.