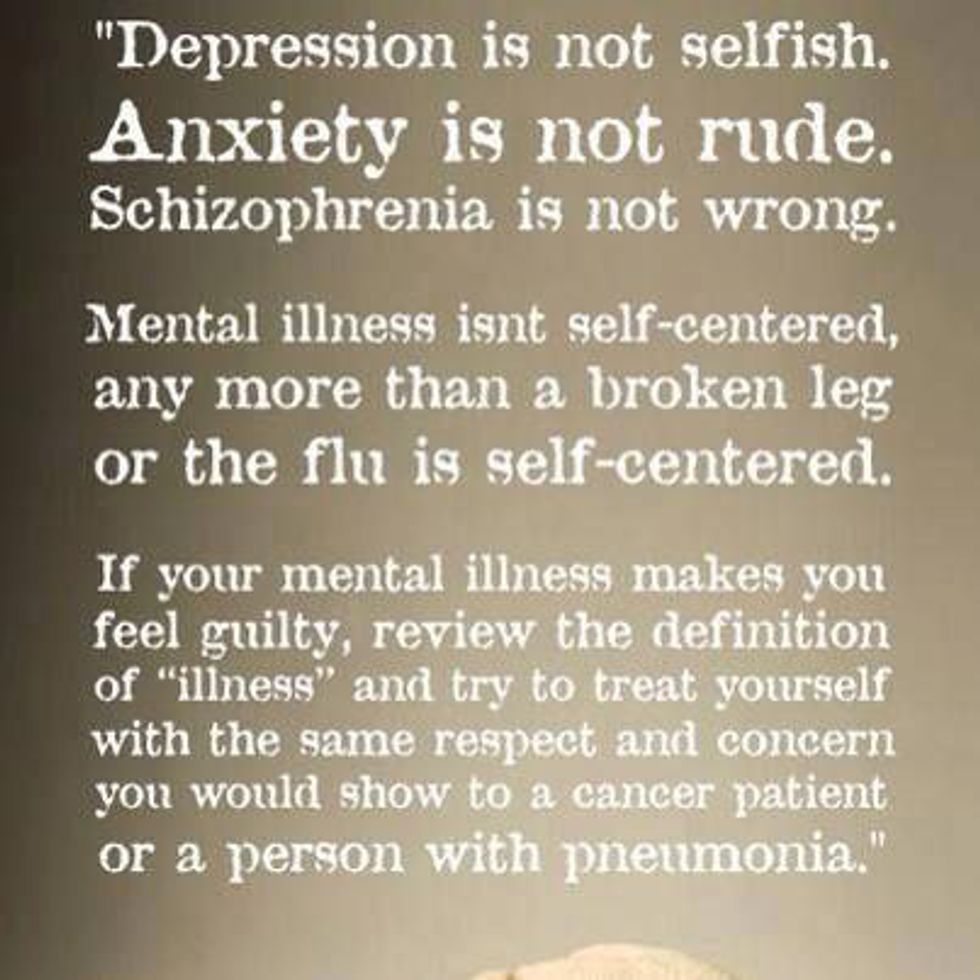

Imagine you've been bedridden by a nasty illness and as you're lying there, head pressurized like a corked volcano, nausea coasting up and down your throat in an angry tide your doctor comes in, looks at you, and says, "Just calm down. There's nothing to be sick over." You'd probably consider throttling your doctor, getting a new one or laughing awkwardly at your doctor's failed attempt at humor, saying, "OK, but what are my real treatment options?"

Now, imagine you are constantly besieged by anxiety about your family, your friends, your finances and anything that floats into your awareness during the day. It's unwavering, unwanted, unhelpful and you just can't make it stop. You go the doctor and she tells you, "Just calm down. There's nothing to be worried over."

We don't doubt the stupidity of telling someone with a physical illness to simply stop being sick. But how do we respond to an invisible illness? An illness or disorder of the mind? Unfortunately, many people are under the impression that mental illness can be fixed by deciding to feel a certain way, snapping yourself out of it, or getting out and doing the things you don't want to do.

As someone who's autobiography could have a chapter comprised of the diagnostic criteria for Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD), I can tell you that willpower and calm words don't magically fix things. Self-determination is of course a huge part of working through any illness or disorder, but saying, "I don't want to feel anxious," doesn't rid you of anxiety. Skeptical? Allow me to bring in the human brain.

As part of my Biopsychology class last spring, I researched Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). You may have read about people's experiences with GAD, but you're less likely to have come across empirical studies detailing neurobiological causes of the disorder. I'm going to discuss research findings about GAD to show you that mental illnesses and disorders are far more intense than mere attitude problems.

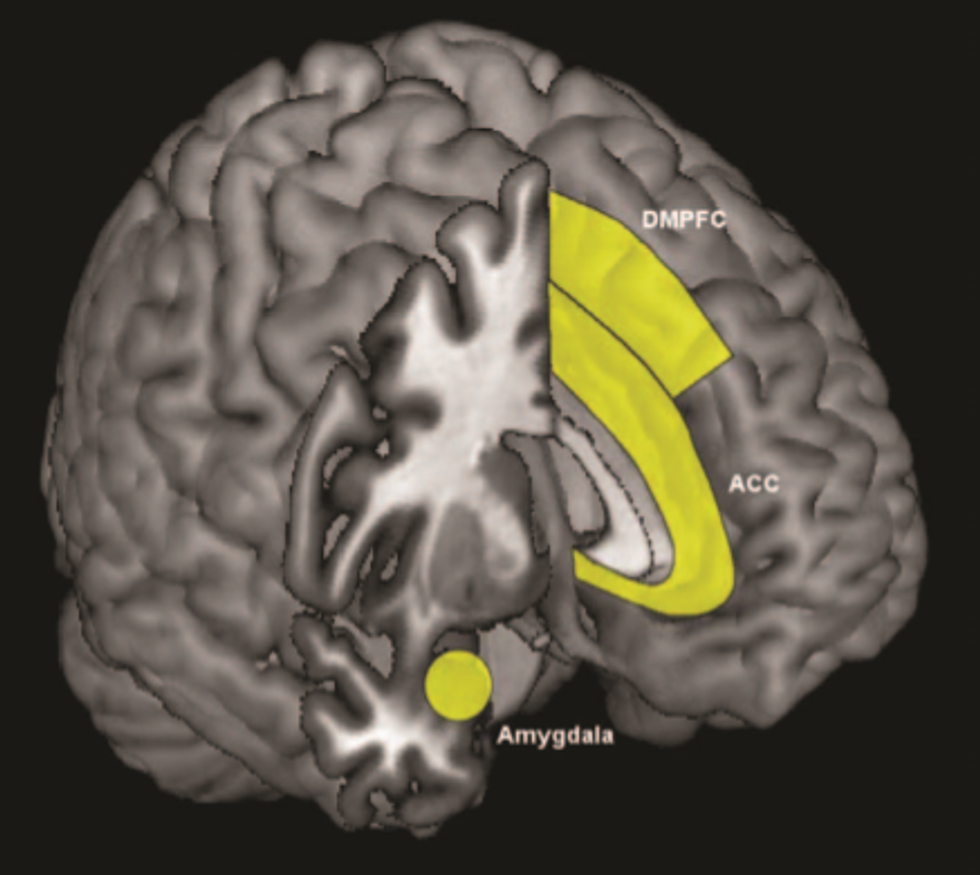

The amygdala and the prefrontal cortices.

The amygdala and prefrontal cortices, primarily the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC), help us deal with future uncertainties and anxiety producing situations. These regions activate with normal worrying as well as with the heightened and at times seemingly unnecessary worrying that is indicative of GAD. The difference for people with GAD, is that elevated activation levels in these regions persist after the worrying has ended. This suggests that people with GAD may not be able to end the worrying process. It may be why people with GAD seem to be in a state of constant, free-floating anxiety.

The amygdala (which mediates emotional responses including physiological reactions) of someone with GAD has increased volume and shows increased activity in reaction to anticipatory signals, experiences of uncertainty, and anxiety producing cues. The GAD amygdala may also have difficulty regulating negative emotions brought on by those cues. The prefrontal cortices seem to contribute to this regulatory difficulty.

The inefficiency in regulating negative emotions is thought to translate into anxiety symptoms. If someone with GAD cannot effectively regulate negative emotions, this may account for the negative expectations and reactions people with GAD experience in daily life.

Read the research article here: Neurobiology and Genetics of Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Neurotransmitters.

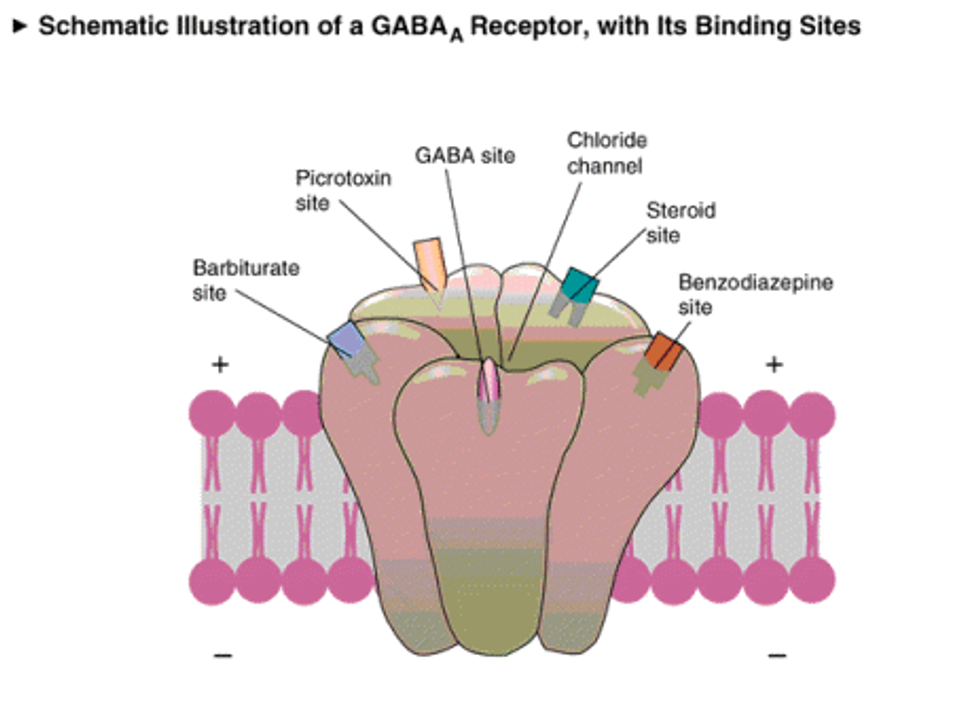

The abnormal communication between the amygdala and ACC is thought to be brought on by decreased inhibitory neurotransmission and or increased excitatory neurotransmission of the neurotransmitter, GABA. (GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter of the brain).

Agents that increase GABA-A binding have effectively treated excessive worry, hypervigilance, and psychomotor symptoms of GAD. This suggests that decreased GABA receptor binding (which is common to people with GAD) contributes to symptoms of GAD. Another neurotransmitter, serotonin, may play a similar role.

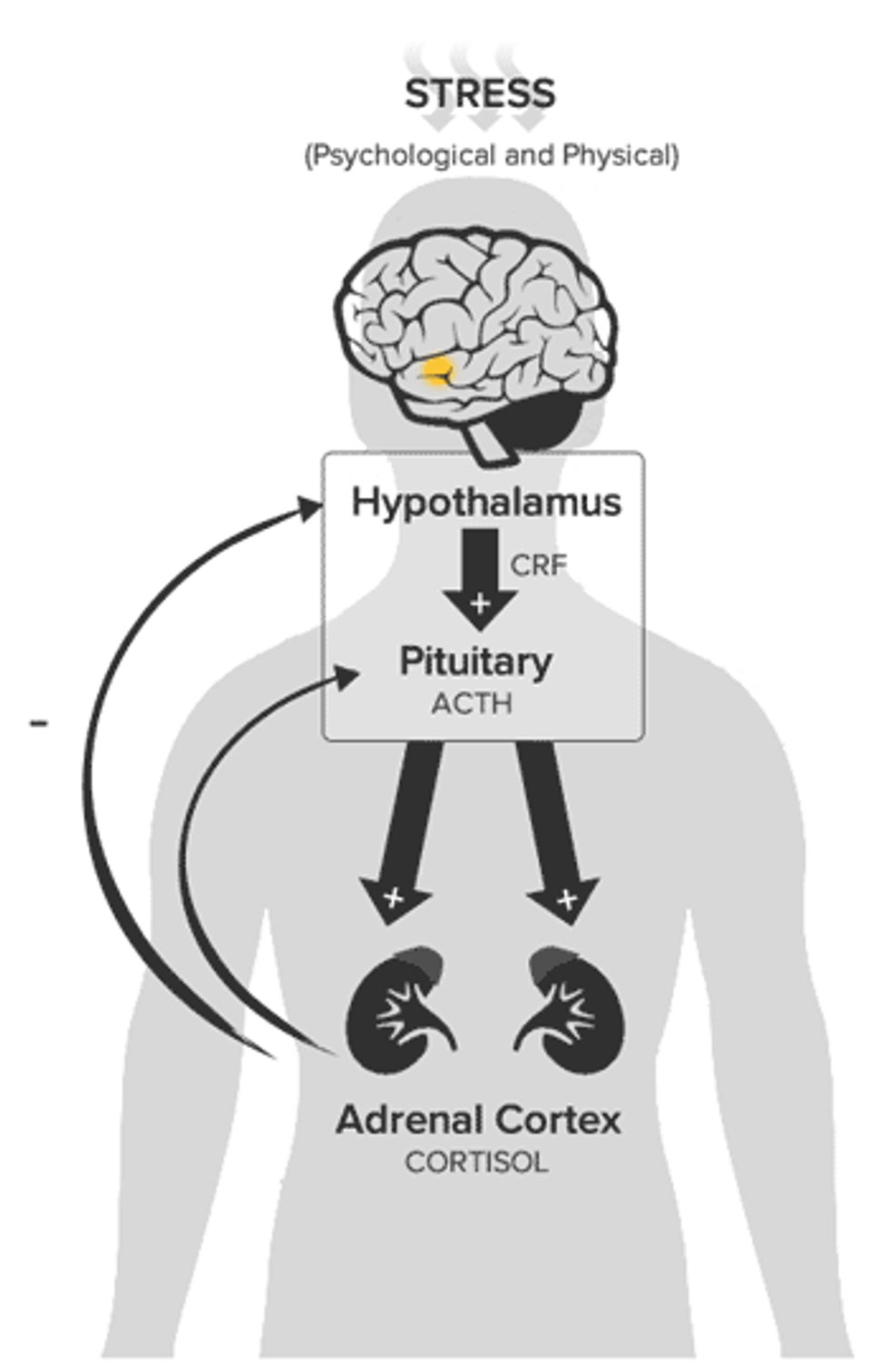

Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA).

Further research is needed to clarify the roles of CRF and the HPA axis, but research has shown that people with GAD may have higher concentrations of CRF in their bodies. And, drugs that reduce CRF concentrations have been shown to reduce these people's anxiety. There is also evidence of excess production of the stress hormone, cortisol, by the HPA axis in people with GAD.

The research I've discussed is by no means exhaustive. There are other neurological factors thought to be involved as well as evidence of genetic contributions and sociocultural factors. This disorder is complex and treatment includes therapy; typically cognitive behavioral therapy, usually in conjunction with Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), or other drugs and lifestyle changes. Different people respond to different treatments, so there is only a framework for treatment, never a one size fits all solution to mental illness and disorders.

Mental illnesses, like anxiety disorders, are real problems that exist in our brains, not in our imagination. While telling someone to calm down or stop feeling a certain way might feel like the easy thing to do, trying to understand and care for someone, is the right thing to do.