I get it. Really, I do.

You want to be cute, you want to be trendy, you’re at some giant festival, and you want to express yourself so you stand out among the sweaty throng. You’re like so totally over the bindi thing and it’s too hot for a turban…

Or maybe it’s a little colder out. End of October, maybe? You need a cool costume to get trashed in—something cool, but still sexy—and kinda cheap, since you spent hundreds of dollars on all those totally bitchin’ festivals last summer…Perhaps your friend just got a new DSLR, and they want to have a photoshoot—with you as the star! Their idea is to shoot something “close to nature,” something kinda wild, definitely animalistic…

Your school’s spirit week is nigh, and thankfully, their mascot is something easily duplicated…

So you in all your brilliance come to the brilliant conclusion that—wait for it—you’ll dress like an Indian! It’s perfect. All you need is some feathers, some fringe, fake buckskin, gaudy turquoise, some moccasins, maybe even a tomahawk, and don’t forget the ever-important war paint.

There’s just one small problem with your new costume.

It’s racist as f*ck.

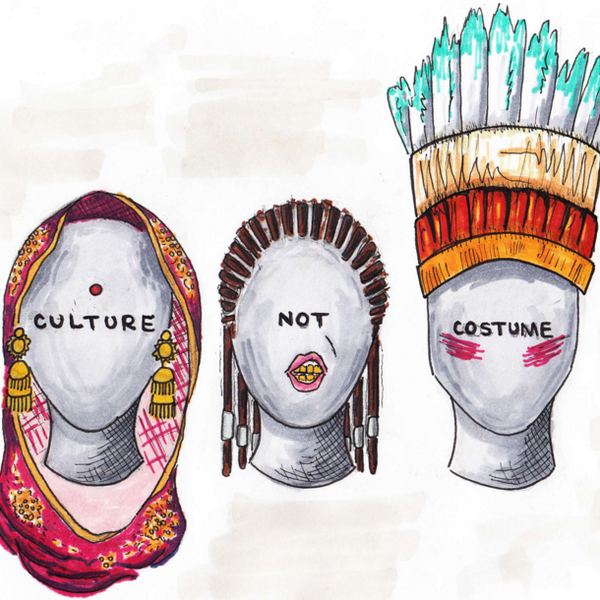

And it’s not a costume. It’s my identity—in fact, it’s a bastardization of the identities of nearly 5 million people. It’s a whole sh*tstorm of hugely offensive cultural appropriation. And you look like a total a**hole.

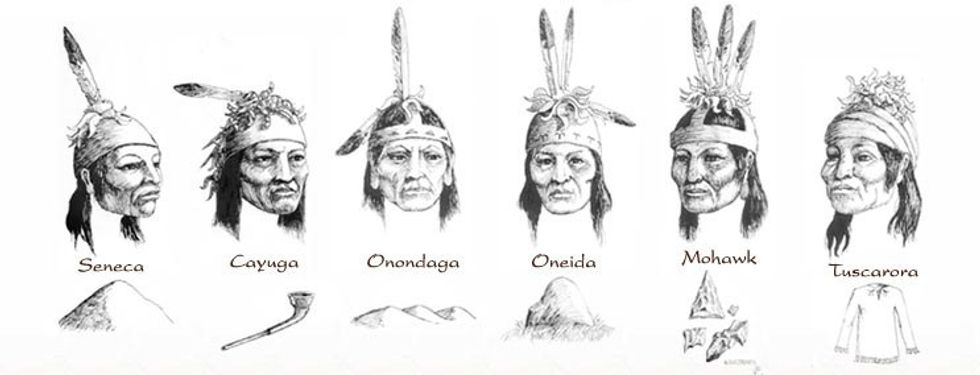

I am a Native American woman. I belong to the Oneida Tribe of Indians. My identity stands tall on its own. It doesn’t need you to support it. So before you step to me with some talk about how you’re honoring my people or appreciating the beauty of my culture—don’t. The last time white people “appreciated” my culture, there was genocide, war, disease, famine.

We’re going to start with the most common form of Native American appropriation—people wearing a headdress, or a war bonnet. To understand why you cannot wear a war bonnet, under any circumstances, you must understand their significance. A war bonnet is typically worn during ceremonies—it's revered as a sacred object—and it is worn only by honored members of the tribe. Notice that I said honored. A war bonnet is something that is earned through hard work and good deeds. It’s not an edgy fashion choice.

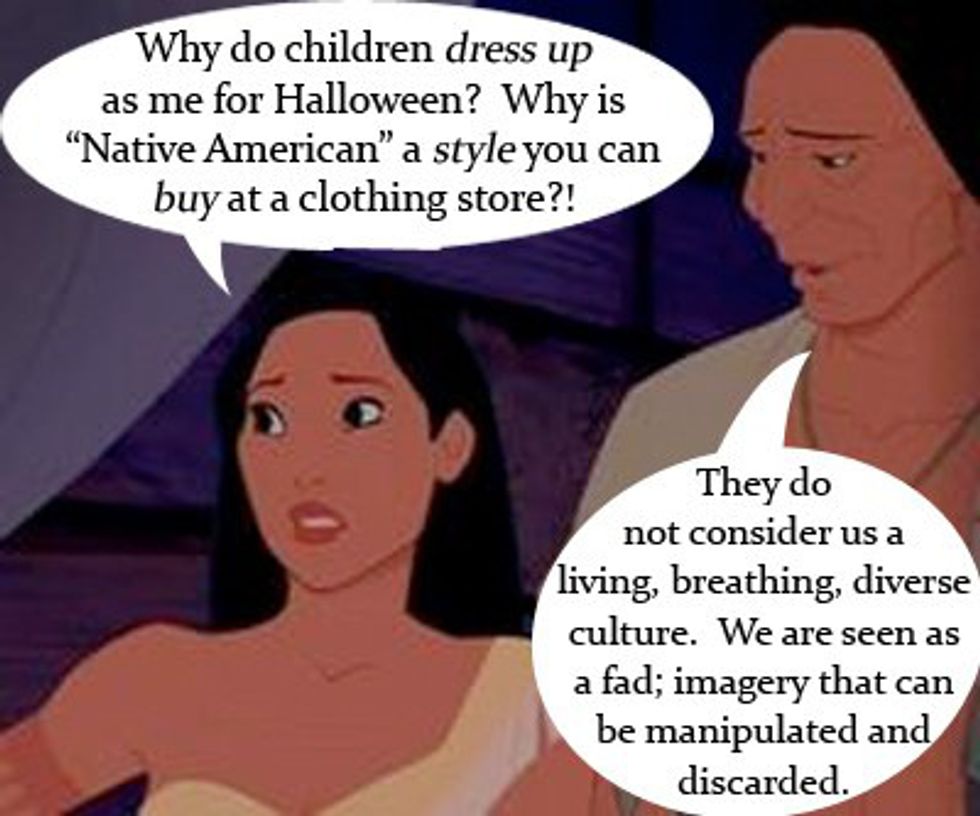

Next on my sh*tlist is people that dress up as an “Indian princess.” You know what I mean. You’ve seen it. Firstly, you need to know that there is no such thing as an Indian princess. Native American royalty is not a thing. When Europeans came over and were faced with the task of understanding the complex social structure of Native American tribes, they did exactly what you’d expect—they didn’t try to understand it at all and simply changed it to fit their ideas of what a society is like.

There are ways to appropriately honor my culture. I agree that it is a beautiful culture. If you really need moccasins THAT badly, buy them from a Native American. Buy Native inspired products ONLY from Native American artists and designers. Not from Urban Outfitters. Native artists aren’t going to sell you anything that is sacred to Native American people, so you don’t have to worry about that. You’ll find a plethora of designs and accessories to satisfy even the most desperate of appropriative cravings. And you’ll be supporting Native American people directly.

Wearing a culture as a costume is not only offensive and detrimental to the real actual living Native Americans who see you brandishing their culture cheaply, you are furthering harmful stereotypes. The Hollywood stereotype of the Native American regalia—yes, that’s the proper term, NOT costume—tries to fit us all into one mold when in fact we are varied in numbers and tribes. More than 500 different tribes exist in modern society—and remember, that’s what exists after genocide.

And you want to condense us all into princesses, braves, squaws, and chiefs.

You are constantly living the benefits of the genocide of my people. The land you live on belongs to my people, and it was stolen and we were massacred on it. It’s that simple.

“You guys shouldn’t have just given us your land, then. You should have fought more! Manifest Destiny!” you exclaim, pumping your fist into the air, holding onto some misguided scrap of misplaced white pride.

“That’s a good point,” I say, “Or, rather, it would be a good point if you had said anything other than what you just said. There were uprisings. We fought back. And because we fought back, we are alive today. I don’t know about thriving, but we are alive.”