Monasteries were plentiful and contained men dedicated to both following and spreading the word of God during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Although there were different orders, the monks that inhabited the medieval monasteries believed themselves to be the disciples of Christ and they lived their lives dedicated to the enrichment of the Christian faith. The monks who followed the Rule of St. Benedict took vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience; however, it is remarkable that the monasteries would be the first in villages to be pillaged and attacked. Due to the historical events of monasteries being the object of pillagers desires, it peaks scholars interest as to why such a pious place would be considered a place full of treasure. Even though the monks took their sacred vows, there is an abundance of wealth, displayed through lavish treasure, decorations, and commissions, that flowed in and out of the monasteries; and one contributing factor to this financial gain is the creation of illuminated manuscripts.

Churches and monasteries were highly regarded as holy and pious places, and although there is some merit to this belief, the religious affiliations heavily gained wealth from the creation of illuminated manuscripts. The original idea behind the creation of bibles were to preserve the Gospel, but as the bibles developed they were sought after by wealthy families and royalty. Ostentatious bibles created an implication of gaining wealth and power by the clergy in regards to further set apart the social status from commoners.

When illuminated manuscripts began to be produced during the Middle ages, they were produced in monasteries by a group of monks who both wrote text and decorated the pages with ornate illuminations. The monasteries housed large libraries full of books and the monks would recreate these books by hand, essentially for the preservation of knowledge.

Manuscripts were created in regards to different purposes, such as ecclesiastical, monastic, lay, and university. In regards to the purpose of manuscripts created for lay use, the Book of Hours is a prime example. Developed in the later part of the Middle Ages, the Book of Hours contained prayers and readings designed for the use in private devotions; however, the manuscripts were extremely elaborate and a book only the wealthy were able to afford.

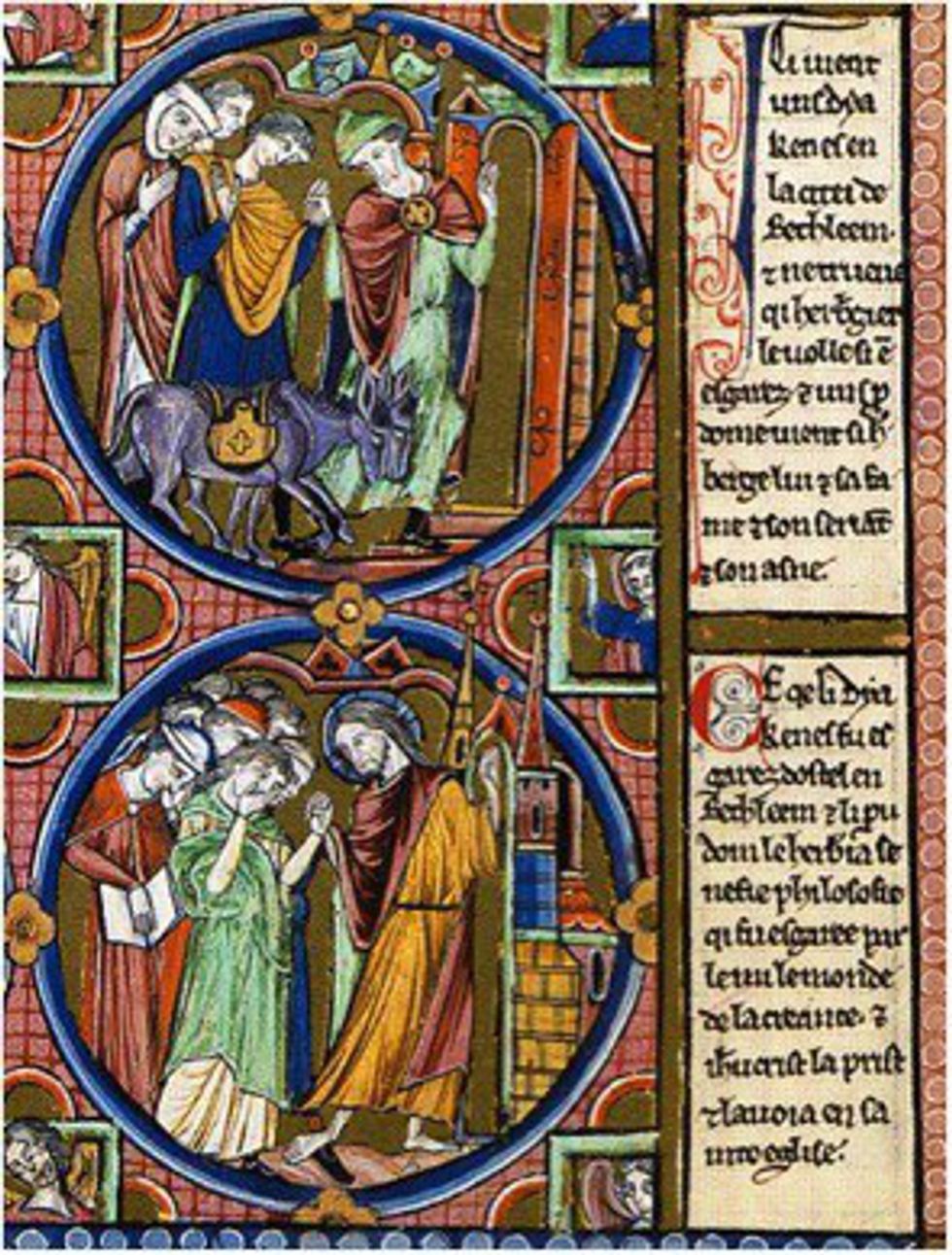

The moralized bibles were made during the thirteenth century in France and Spain. They were made up of thousands of illustrations and each story is represented in several pages, for example: multiple illustrations were present for each story because an illustration was created for every few sentences. Each page of the moralized bibles contains eight circles, roundels, that house the illustrations. A small amount of text accompanies each roundel, but the majority of the moralized bibles are illustrations. In fact, each bible contains roughly 5,000 illuminations that are aiming to be used as visual aids for preaching and evangelization.

Manuscripts of this magnitude was not an easy endeavor, which brings to light the amount of work and dedication it took to create such artworks. The moralized bibles are among the most expensive medieval manuscripts, and are recognized as excluding the layman and are not, “Bibles for the poor.” Manuscripts of this extent were generally commissioned by royal families and other wealthy families, or reserved for theological studies.

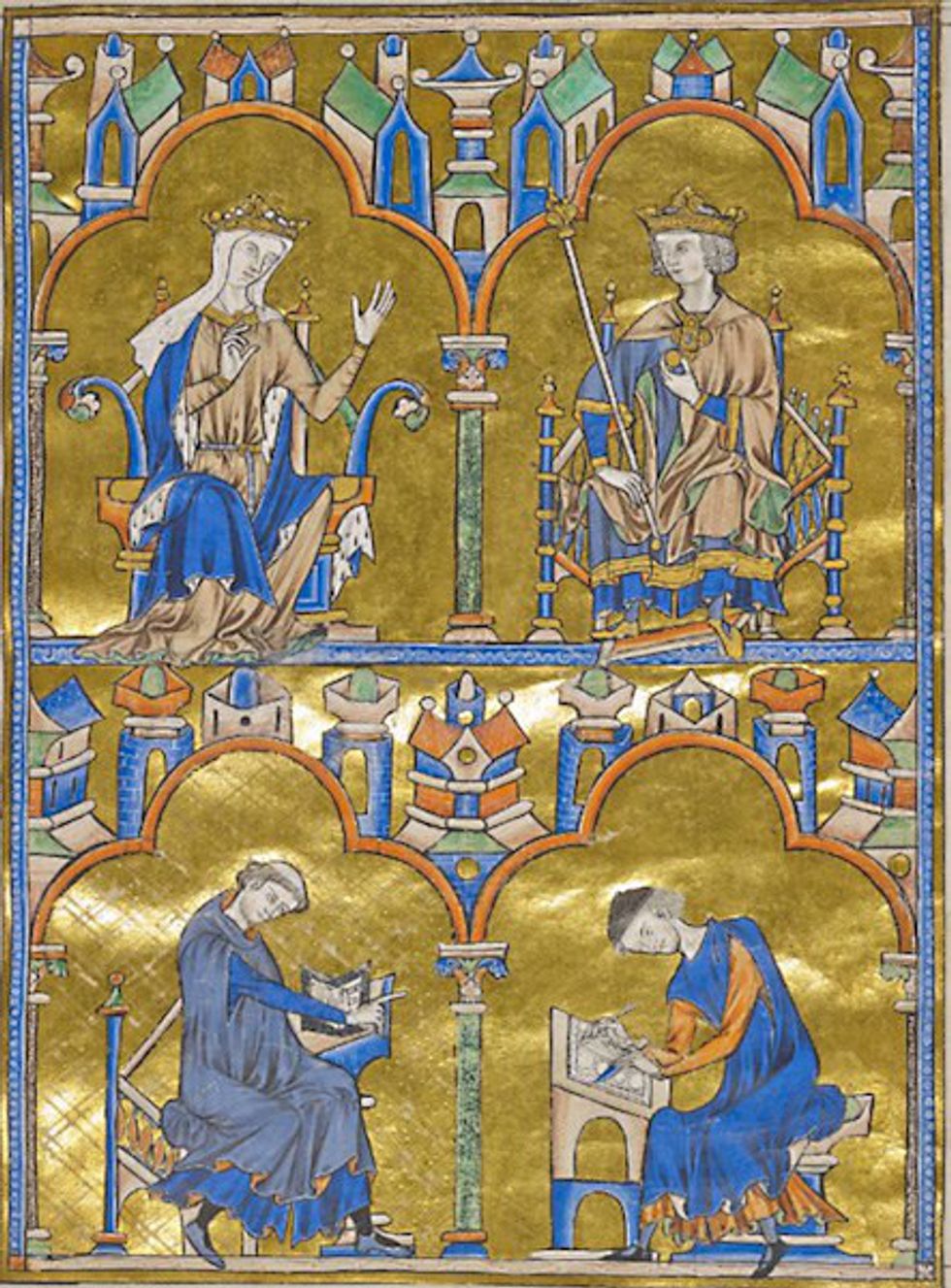

A prime example would be the Bible of Saint Louis, a moralized bible produced roughly around 1230 in Paris. The Bible of Saint Louis belonged to both Blanche of Castile and King Louis IX of France, and within the bible a dedication page to the royal owners can be located. On the dedication page of this bible are references to Blanch of Castille, King Louis, the author, and the scribe. Two different realms are present: Blanche of Castille and King Louis are located at the top and the creators of the manuscripts are located on the bottom. Similar to the hierarchy of the time, the King and his mother are placed above the “commoners".

Also located on the dedication page are images that represent the author and the scribe working on a representational bible for the owners of the Saint Louis Bible, which indicates the process of the production of illuminated manuscripts. The illuminated bibles were created for royal and wealthy families as oppose to being created in order to preserve and share the knowledge of the faith with everyone. The background contains images shaped as buildings and houses, which could easily represent common dwellings within the cities. However, similar to the exclusivity of the moralized bibles, the remaining people of the city were pushed to the background, and the moralized bibles are only handled by the four representational figures found within the dedication page of the Bible of Saint Louis: the wealthy (King Louis and Blanch of Castile), the author, and the scribe.

Bernard of Clairvaux was an advocate for the Cistercian order and wrote a sermon regarding the excess and criticism found within the Cluniac Abbeys and other churches. Bernard’s Apology is a prime literary source to rival the lavishly decorated manuscripts produced by the monasteries. In reference to excessively large and ornate architecture Bernard states, “Tell me, oh pontiffs, what is gold doing in the sanctuary?” This statement from Bernard’s original writing is translated by David Burr into, “Tell me, poor men, if you are really poor what is gold doing in the sanctuary?” Every manuscript referenced thus far contains an enormous amount of gold detailing with the illustrations. In regards to Bernard’s Apology, the use of gold within the church was considered excessive and contradictory to the vows taken by the monks. For monks to take vows of poverty and create golden bibles from receiving gold as payment is a highly unethical practice for the monasteries to engage.

Bernard continues his writing to further explain the “idolatry” the monasteries are responsible for due to their greed, in which he states, “there is more admiration for beauty than veneration for sanctity.” Just like the Codex Sinaiticus was originally developed to document and spread the Gospel, the greed of the church inevitably turned the bible into an object of beauty. The focus the monks contributed to the illuminated manuscripts, hindered the ability to uphold their vows and display their obedience to the faith. Instead of helping the needy, the monasteries were preoccupied with commissions to create lavishly ornate manuscripts for wealthy patrons. Although Bernard never addressed the issue of illuminated manuscripts in his Apology, he still manages to inadvertently address the issue with his overall disdain of the monasteries greed and desire for wealth. He states, “the curious find something to amuse them and the needy find nothing to sustain them.” The idea of the illuminated manuscripts actually spreading the Christian word and helping the needy is moot due to the fact that the illuminated manuscripts were only able to be purchased by the wealthy.

After a look into different manuscripts and a critical theory analysis of Bernard of Clairvaux’s Apology, the greed that drove the creation of illuminated manuscripts unfolds. The church had an inevitable amount of wealth and power to gain from created such lavish manuscripts under the commissions from the royal and wealthy families. The illuminated manuscripts created to spread the word of the Christian faith only touched the hand of those who were not in need. Bernard stated, “the brighter the colors, the saintlier he’ll appear to them.” In order for the monasteries to make money, it was not enough to spread the Gospel, but they must reach the wealthy through Christian luxuries.