Many people believe that the next generation of kids will play with gender neutral toys.

The movement to end gendered toys for boys and girls has begun. Big companies like Target have removed all gender-labeling in their toy aisles. Of course it is good to think beyond pink and blue toys and look toward fighting traditional gender stereotypes, but children are not gender-neutral, and tend to resist efforts to make them so.

A 2012 cross-cultural study on sex differences confirmed what most of us see: despite some exceptions, females tend to be more sensitive, esthetic, sentimental, intuitive, and tender-minded, while males tend to be more utilitarian, objective, unsentimental, and tough-minded.

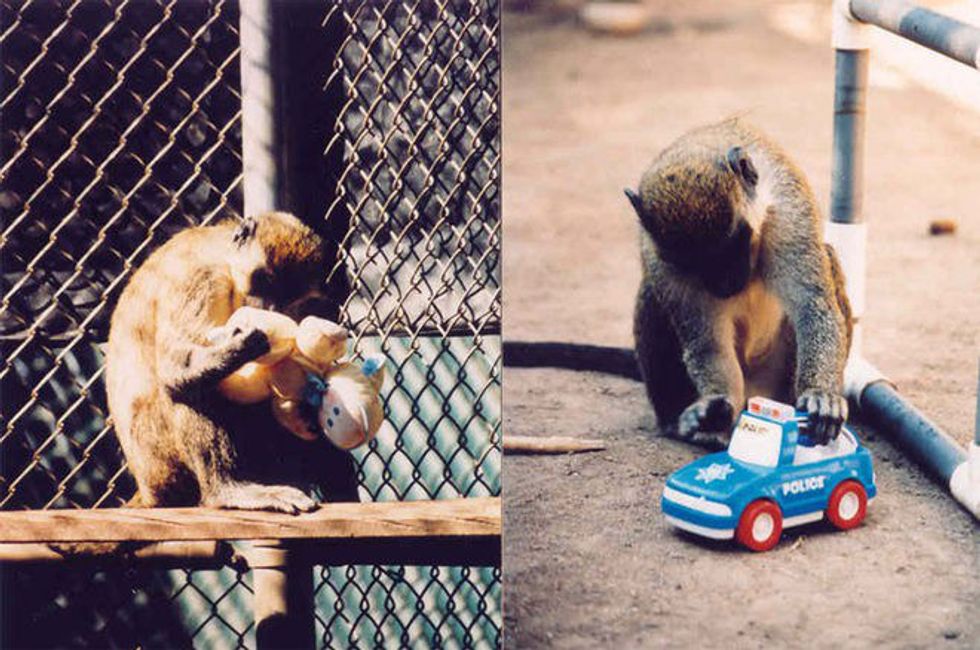

Of course societal norms on what it means to play "male" and "female roles does affect young children, who are saturated with these gendered images through the media. It must be noted that the female penchant for nurturing play and the male propensity for rough-and-tumble hold cross-culturally and even cross-species. Among our close relatives, such as rhesus and vervet monkeys, researchers have found that females play with dolls far more than do their brothers, who prefer balls and toy cars.

A researcher who explained the data said "children recognize that certain objects in their environment are appropriate for certain activities." They could be looking at a certain toy because it facilitates an activity they like; according to this data, there is no such harm in allowing often intense sex differences to flourish in early childhood.

Femininist sociologist Elizabeth Sweet accused the toy industry of marketing toys to girls that convey an insidious message: “Girls can be anything—as long as it’s passive and beauty-focused.” But are girls today really being held back? Has any generation of girls ever been offered a greater variety of opportunities and encouragements? If our monkey relatives have any say in the matter, most girls don't even want to play with the same toys as boys do.

So how is it possible to market every toy to boys and girls?

Let's look at Lego. Lego spent four years investigating and experimenting on the gendered toy dilemma. They had a wide range of children build a castle. For the boys, the castle was a hastily constructed scene in which the main event—the battle between the Lego figures—took place. For the girls, the castle itself was central, and they wanted to know what was going on inside. Unlike the boys, the girls wanted detailed and personalized characters. The boys wanted a battle.

Don't shrug this off quite yet; maybe the activists can learn something from the practitioners.

From working at a summer camp, I have experienced the divide of how girls and boys play. Typical girl play seems relatively calm and passive on the surface, but girls are interested in our own kind of domination. Our play is full of conflict and imaginary power struggles, and their fantasies are just as complex, intense, and inventive as boys’—but manifestly different. The boys wanted to play active games, like capture the flag. The girls would rather sit on the sidelines and talk with each other. For myself, forcing someone to play a game or with toys they are not interested seems like a good way to have an unhappy child on your hands.

We want our kids to be exposed to a wide variety of toys, and to be tolerant of all toys. There should be no hierarchy of which toys are better for boys or for girls. A girl or boy playing with a princesses can be just as powerful as any superhero. Maybe we need to change the norm that princesses are passive in order to create a more equal playing field for gender neutral toys.