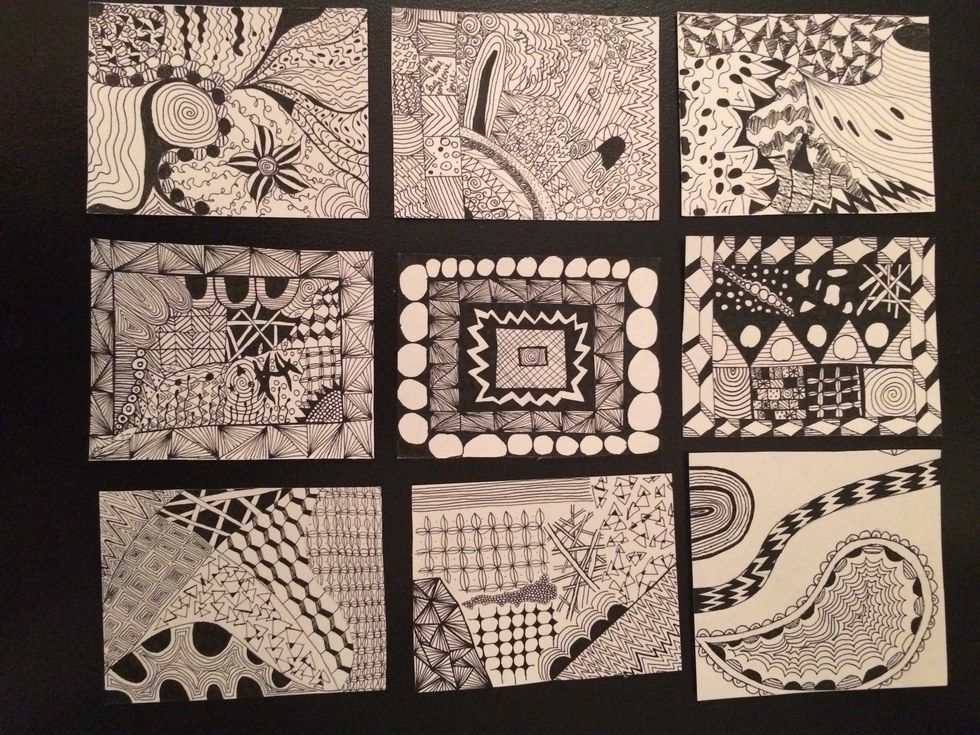

I pass Charlotte a thick black Sharpie so she can move onto her next design. She’s drawn the outline of a flower on a square piece of white cardstock and starts filling in the petals with Zentangle doodles. I’ve sketched my initials in block letters on my own piece of paper. Lulu sits across from us at the table, making zigzags in the middle of a heart with a thin black marker.

We sit under a colorful ceiling made up of tiles painted by children in the art group. Dream catchers woven from yarn and feathers, crafted by other hospital visitors, dangle from the ceiling. This art program is highly selective. Only the long-term pediatric patients at Georgetown University Hospital can be a part of it.

We’re sitting in the hospital’s outpatient clinic practicing Zentangle, a new form of art therapy, which helps calm Charlotte and Lulu before seeing the doctors. Drawing repetitive patterns help to relax patients and distract them from the pains of treatment. The only tools needed: pen and paper.

Most of the patients in the clinic’s art therapy program are being treated for cancer, blood disorders, or have had a transplant. My sister Charlotte was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer, acute promyelocytic leukemia, on Halloween of 2014. She was enjoying her senior year of high school when doctors told her she’d never be able to go back to class. Charlotte had blackouts while running on the field hockey turf, and her gums bled every night after she brushed her teeth. She hid her symptoms from our family. She knew if she said anything, she’d have to get a blood test. Her crippling fear of needles kept her quiet for weeks. She almost died of internal bleeding by the time our mother noticed bruises on her legs and brought her into the hospital.

Charlotte’s serious fear of needles made her the perfect candidate for Zentangle. When doctors first admitted her into the hospital, she refused to move or look at her left arm, the arm connected to an IV stand by needles and tubes. The art therapists at Georgetown were the first to get her to move her arm by having her start a creative project. She made collages and friendship bracelets, but Zentangle quickly became her favorite activity. She practiced the easy-to-follow designs to curb her anxiety while waiting to get a shot or a blood transfusion. Zentangle kept her occupied while the nurses wiped down the injection spot on her skin and prepared the needles. The first few weeks of treatment were a nightmare for my entire family. Charlotte turned out to be allergic to the blood from her transfusions and she suffered from retinoic acid syndrome, a life-threatening side effect of her APL chemotherapy. She couldn’t walk for weeks afterward, so she spent a lot of time doodling in bed.

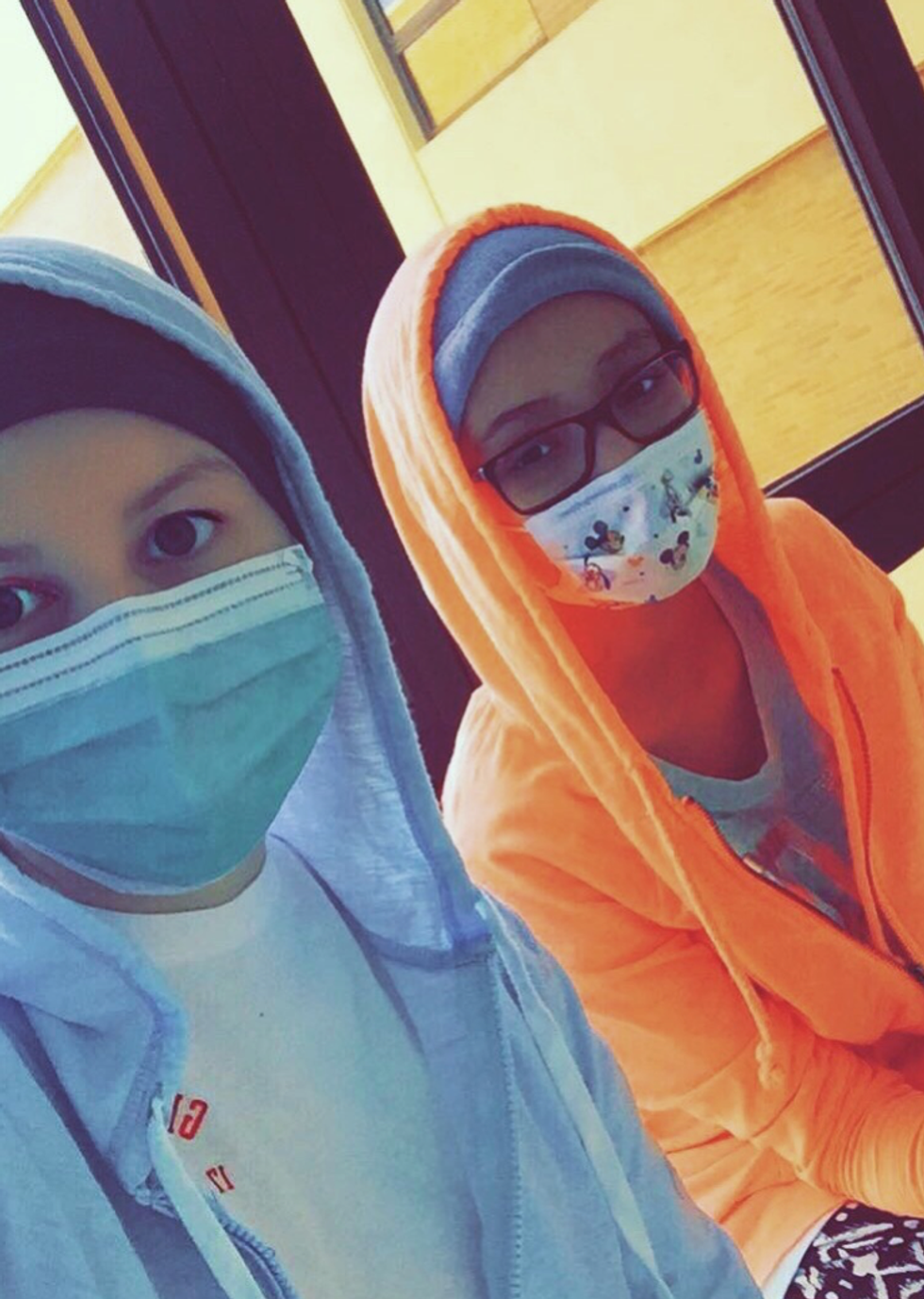

16-year-old Lulu joined Charlotte on the fifth floor of the hospital in late March of 2015. She had a bad cough for months before doctors in her home of Kuwait City diagnosed her with advanced Hodgkin lymphoma. They advised her to get treated in the United States. Lulu left behind her three younger sisters, friends and family members in Kuwait to spend the next eight months of her life in Washington, DC. Lulu and Charlotte quickly became close. Charlotte couldn’t go to senior prom or to college on time. Lulu missed a year of school with her classmates. These two high schoolers used Zentangle to help cope with the confusion and stress of their diagnoses.

Art therapy helps not only pediatric patients but also their siblings and parents, who feel just as upset, stressed and confused about a cancer diagnosis. The art therapists at Georgetown always bring extra supplies to patients’ rooms so everyone can be included in projects. There are activities for every age group and Zentangle is a type of art for an older group.

The benefits of art therapy, specifically Zentangle, overlap greatly with the benefits of meditation. Art therapy helps patients and their families feel in control while most areas of their lives are out of control. Sick children have full power over their drawings, paintings and crafts, helping them forget their feelings of helplessness associated with their uncooperative bodies. Most art therapy activities emphasize some element of repetition, which relaxes the mind and puts the patient in a state of meditation, according to Dr. Cathy Malchiodi. The hospital’s bright lights, rooms with crying and screaming children, beeping machines, and constant conversations between the nurses and doctors create a stressful environment. Art therapy gives these children something new and fun to focus on while in a hectic setting. They feel accomplished and proud after creating a piece of art, leading to feelings of confidence and increased self-esteem and happiness.

One of the newer additions to the art therapy program at Georgetown Hospital is the form of doodle art called Zentangle. The Zentangle method is only a couple of years old but has already gained international popularity among art therapists because it requires few supplies. A lot of the activities on the pediatric oncology floor are for elementary school aged children, so Zentangle is something new for older patients and their parents. “I got a Disney princess coloring book my first month here,” says Charlotte. “I thought I’d be getting little kid stuff the whole time.”

Charlotte was diagnosed at 17 years old, which gave her access to the pediatric floor. The only tools anyone needs to make a Zentangle design is a pen and paper. It's great because patients can practice drawing designs while away from the hospital. The hope is that these children will use Zentangle to deal with stress even while outside of the hospital.

Zentangle helps participants learn how to deal with mistakes, according to Georgetown's art therapists. By using a pen, patients and their family members can’t erase anything. The goal is to move on and keep drawing even if the design isn’t perfect, according to Georgetown's art therapists. Hospital life is unpredictable and Zentangle helps patients practice calmness when something unexpected arises, which could be a drawing mistake or something like a neutropenic fever.

Charlotte liked Zentangle immediately. She now uses it before having her chest port accessed to feed medicine into her blood stream, because it distracts her from her fear of needles. When she was first admitted, she struggled when nurses drew her blood or switched IV needles, which happened every day, and sometimes every hour. My entire family now enjoys drawing Zentangle patterns. I like to doodle during plane rides or when I feel stressed during finals week because it helps me clear my head. I didn’t know the continued benefits of practicing Zentangle outside of the hospital setting until I brought an official Zentangle book to school with me.

“I hardly watch TV when I’m here and don’t feel like doing schoolwork so I’ve loved the art therapy program,” Charlotte says about clinic visits and overnight stays on the inpatient floor. She plans to bring a Zentangle sketchpad with her to college next year and will use other pieces of art she’s created this year as dorm room decorations. She smiles sitting in the clinic and glances over at Lulu’s progress on her Zentangle design.

“Charlotte Hay,” a nurse calls out. She slides her Zentangle flower to me to hold onto while she heads into the operating room to be sedated for her monthly bone marrow biopsy.