Just one look at Tura Satana's bustier-than-life go-go dancer Varla relegates the 1965 film Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!to the lowly status of a sexploitation movie; from the start, it is unable to regard the entire package as anything but a novelty. In spite of, or perhaps because of its notorious critical failure, it has often been reexamined by critics and, over time, has garnered high praise from feminists and film critics alike.

Life's funny like that sometimes.

Like the works of Edgar Allan Poe or Vincent Van Gogh, a movie is sometimes unfairly labeled as "bad," and shunted aside for the next week's new release. It gets filed away as a dud and for every Faster, Pussycat!, there are dozens of rhinestones-in-the-rough which are forgotten about. It is my hope to dust off these cinematic-crapfests and try to salvage them in my own fledgling series I've so cleverly named "Redemption".

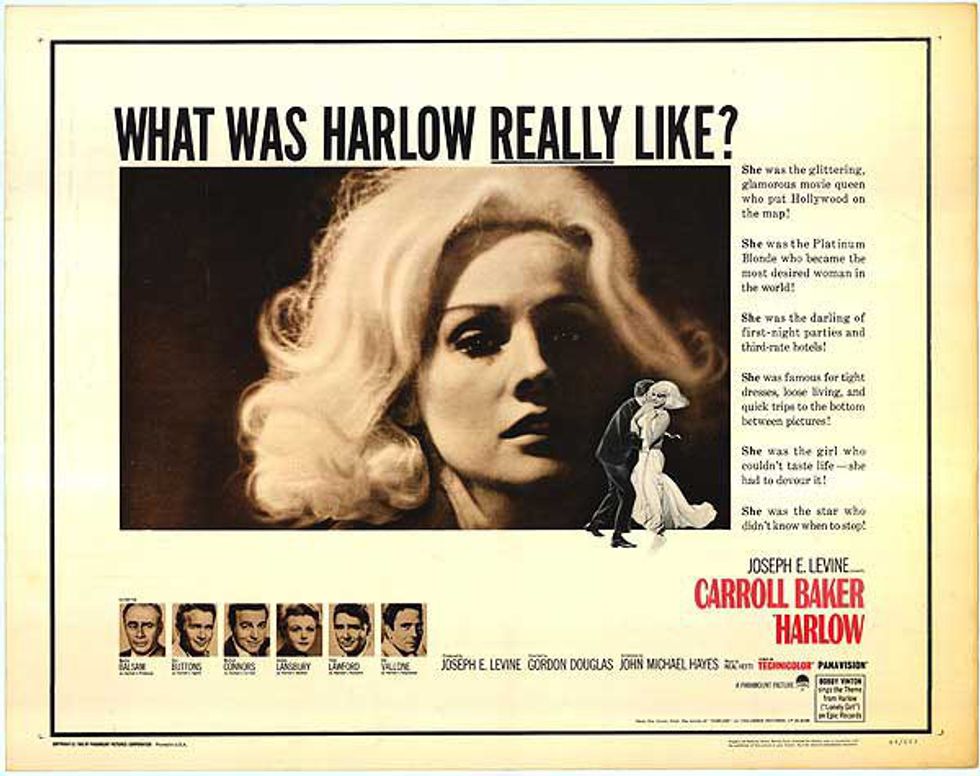

Last week, I reviewed a film which, in its own misguided way, attempted to shed light on the corrupting influence of Hollywood. Continuing in that oddly specific vein of 1960s Hollywood movies about Hollywood, this week's offender is Harlow, a highly-fictionalized and unflattering recounting of the life of Jean Harlow.

That is Jean Harlow, the original "blonde bombshell," one of the biggest movie stars of the 1930s, and, before her tragic death in 1937 at the age of 26, one of the world's most iconic sex symbols. Her story, while short, is rife with possibility, possibility which the film squanders scene after scene.

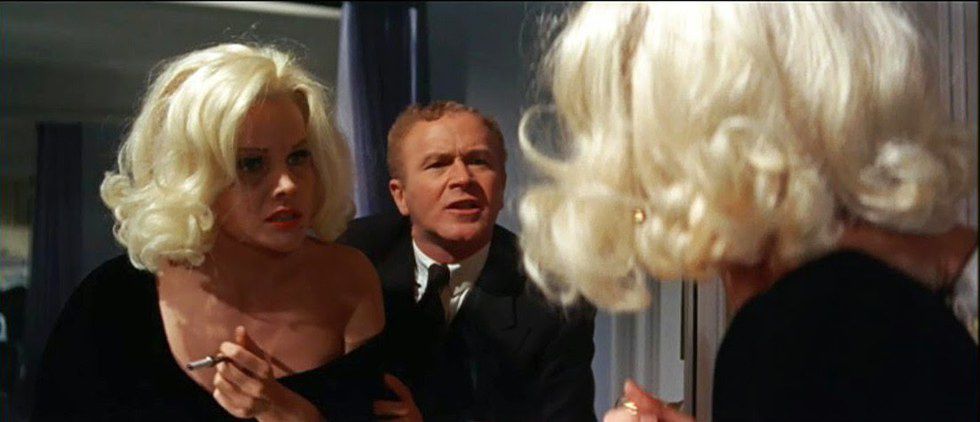

The opening of the film is stunningly raw while managing to somehow simultaneously be opulent. It offers insight into the fictional "Majestic Studios," as hundreds upon hundreds of extras file in reporting for another day of decidedly unglamorous work. The cinematography, without a word, manages to demystifying those "halcyon" days of Old Hollywood and is replete with an almost overwhelmingly Baz Luhrmann-esque quality, setting the stage for what is sure to be a engrossingly sordid story. Harlow (played by the exceptionally talented Carroll Baker, who once again plays a woman with "the body of a woman but the emotions of a child" [and did it far better in 1956's Baby Doll]) is picked out of a lineup and, after failing to submit to the casting couch, is unceremoniously dropped from the film, returning home to her milquetoast mother (Angela Lansbury) and her unemployed lothario stepfather (Raf Vallone). What follows, as with any biopic, is a meteoric rise to fame wrought with devious hangers-on, handsy executives, and a surprisingly, unrealistically supportive (and non-lascivious) agent, played to perfection by Red Buttons.

The film is a largely self-contradictory mess which spins in circles until it finally collapses in a stinking heap and is, quite honestly, an insult to the legacy of Jean Harlow. It is reductive in the extreme, and the fact that the names of films, major figures, and studios are all fictionalized gives the impression of a half-baked film; acquiring the life rights must have been a struggle. And while there are a number of truly riveting scenes (the opening, a tense family meeting regarding her signing her first contract, Red Buttons explaining what he sees in his new client to his suspicious wife), the movie is dragged down by a nonstop parade of tawdry sex, discussions of sex, yearning for sex, thinking of sex; it's as if the producers and writers knew nothing of her life other than the fact that she was a sex symbol who died far too young. Jean Harlow may be a hallowed name in the pantheon of cinematic sexpots, but according to this film, every moment of her life, onscreen and off, was centered entirely around it. Sex is a part of life but, much like this paragraph, it quickly becomes exhausting and any stirrings of lust on the part of the audience turn quickly to anger and annoyance.

In addition to the one-track mind of the scriptwriters, there is a distinct lack of emotional complexity which makes it nearly impossible for the viewer to empathize with Baker's characterization. Her toughness and cynicism in the face of the monolithic, omnipotent Hollywood machine, while rife with possibility, is betrayed by her overt codependence on the men in her life and eventually surpasses self-assuredness and becomes grating. Baker seemed to excel in these roles of infantilized, hypersexualized woman, but the toughness which the role necessitates does not mesh well with her cloying, wide-eyed innocence. Because of the seemingly-irreconcilable aspects of her personality, and the palpable lack of depth to the tragically-fated movie queen, it is never made clear how or why Harlow created a legacy for herself. Her acting ability is constantly called into question (though the American Film Institute ranked her the 22nd greatest American actress of all time) and, because none of the titles of her films are used, this movie exists in a kind of cultural vacuum, isolated from her works and her impact.

The dialogue vacillates between coarse and schmaltzy ("Imitation is the sincerest form of failure. You be you, an original Jean Harlow." - gag) and takes on melodramatic proportions that surpass drama and become full-fledged, kabuki-style, unintentional comedy. The writers apparently attempted to atone for what they knew must have been a lackluster effort because there are numerous instances of Harlow's comparing heated arguments and hackneyed rejoinders to a Hollywood film, registering as some kind of admission of defeat by the writers. After one excruciatingly long argument regarding her new husband's impotence, his suicide strikes one as a laughably extreme (and unrealistic) reaction. One almost feels compelled to step through the screen and offer Paul Bern (Harlow's husband, a nonfictional name for a change) a handful of Cialis and a pat on the shoulder to get the ball rolling again.

The editing is exceptionally bad, with jarring transitions robbing potentially poignant scenes of an opportunity to land and have a real kind of impact upon the audience. Because I must give credit where credit is due, however, there are a handful of juxtapositions of scenes that work well, most exceptionally the scene in which her agent exclaims that her's is a face America must see, immediately followed by her getting a pie in the face.

Final Verdict: Her sexual magnetism and comic ability were what made Jean Harlow one of the biggest film stars of her day and a lasting cultural figure. Unfortunately, this film, while beautifully capturing the sinfully excessive grandeur of pre-Code Hollywood, squashes whatever warmth and empathy the real Harlow relayed on the screen. This laughably simplistic film is the cinematic equivalent of a third grader giving an impromptu book report (or, for those of you as slavishly devoted to pop culture as I am, Jenna Maroney's ill-fated Janis Joplin biopic ["Jackie Jormp-Jomp] on "30 Rock"). It is a shallow, spiteful film which takes the compelling story of a young woman who died in the prime of her life and presents her, untruthfully and unconvincingly, as the shrill, selfish physical embodiment of sex, empathy and likability be damned. It is a vapid waste of potential and a cruel, unnecessary jab at the life and legacy of Jean Harlow made in the worst of taste. And while there is no greater fan of a lurid, showbiz-centered film than I, Harlow is moreso an act of malice than a fun exercise in tastelessness. Redemption Denied.