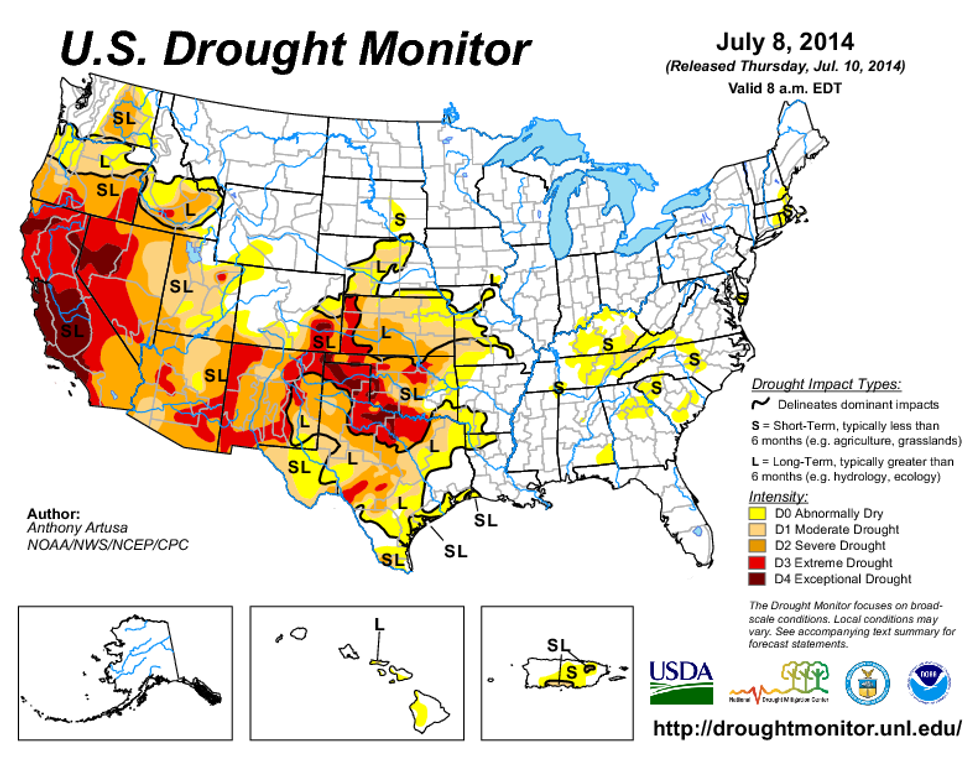

In 2012, California experienced its one of the driest years since record-keeping began 118 years ago. Since then temperatures have continued rising and rain has stopped falling. Governor Jerry Brown declared a state of emergency in 2014. As the drought continued into 2016, Brown issued an order to continue water-saving procedures, and declared that the drought is California’s “new normal.” Environmental historians argue that this new normal may in fact be an old one. Researchers posit that California has a history of moving from wet periods to dry periods, interspersed with megadroughts-- that is, droughts lasting two decades or more. The current drought in California is the longest dry spell in the last 1200 years, but it may not be so unprecedented when we look at California’s environmental history of dry periods.

Humans began recording climate change in the late 1800s. Since the 1990s, there have been nine periods considered much drier than the rest, and California is currently in one. In order to learn about droughts prior to the 1800s researchers must look beyond written texts. Scientists often find drought evidence in the growth rings of tree trunks. A thin ring means growth was stunted by a lack of water that year. Many historic droughts were first discovered by studying tree rings. However, different kinds of research went into discovering megadroughts.

Researchers like paleoclimatologist B. Lynn Ingram not only looked closely at tree rings, but studied microorganisms in ocean sediment to determine temperatures and dry periods over the past millennium. In the 1990s Scott Stine, a professor at CSU East Bay, took advantage of the declined levels of lakes and streams in the eastern Sierra Nevadas to study tree stumps that had been submerged for hundreds of years. Stine was able to reconstruct ancient water levels, and thus the drought history of the area, by using radioactive carbon techniques and noting the elevations of the stumps. Through the work of these scientists, we know that California has experienced at least two megadroughts, one in the 9th century, and one in the 13th. Research also shows that temperatures rose in what is now the western United States from about CE 800-1300, the 7th through 12th centuries. These rising temperatures resulted in a series of droughts, which were devastating in their frequency if not their length. Several that occurred in the mid-11th and 12th centuries edged into megadrought territory, but not in California. Some scientists refer to this time as the “Medieval Warm Period,” and attribute part of it to a cooling phase of the PDO.

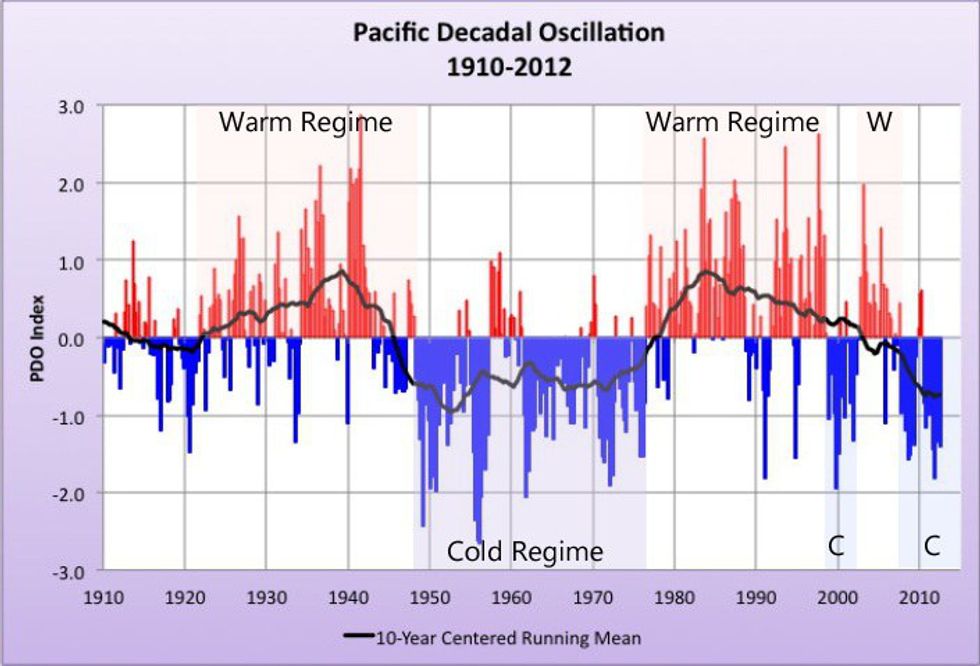

Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), a term coined by fisheries scientist Steven Hare in 1996, is a climate pattern similar to El Niño (ENSO). Hare identified this pattern while researching connections between the production cycles of Alaskan salmon and the climate of the Pacific ocean. PDO and ENSO operate with similar spatial climate fingerprints, but have shown very different behaviors over time. PDO is different from El Niño in that 20th century PDO events have persisted for two to three decades, while El Niño events only to persist for six to eighteen months. Also, the climatic fingerprints of the PDO are most visible in North America, with secondary signatures existing in the tropics, while the opposite is true of El Nino. Researchers have found evidence for two full PDO cycles in the past century. Cool phases of the PDO allow for less precipitation, because cool sea temperatures move the jet stream north, pushing off storms that could bring rain and snow to California. B. Lyn Ingram says lakes in California dried up during a cool phase of the PDO several thousand years ago, while warmer phases of the PDO have caused numerous storms along the California coast. The PDO has been in a fairly cold phase since the early 2000s, meaning that the current California drought makes sense not only as a product of warming on land, but also as a product of ocean temperature. However, experts warn against blaming the entire drought on the PDO.

Few experts have expressed certain belief that California is in a megadrought. Many researchers attribute California’s troubles to a larger and longer dry spell affecting much of the West, Southwest, and Plains. Jonathan Peck says that “The California drought is kind of the latest worst place.” This overall dry spell began eighteen years ago, after the last strong El Nino. Richard Seager, a climate scientist at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, NY, says that what we are seeing is edging into the territory of a megadrought. It has been said that California might get relief during this year’s El Nino, but the weather pattern has not brought any particularly strong winter storms as of yet. Most climate models show Northern California to becoming slightly wetter in the next decades, but the state as a whole is expected to continue warming, and climate change adds to worries about a megadrought.

Today’s experience of warming is separated from ancient and medieval warming periods by two major factors. Medieval warming is thought to have been fostered by a combination of increased solar irradiance and decreased volcanic activity, whereas today’s warming is attributed to greenhouse gas emissions. Also, medieval times were characterized by summer warming, but today, not only are summers longer and hotter in California, but spring and winter temperatures are expected to increase. These increases manifest in things such as decreased winter snowpack and earlier spring river discharge.

Humans built California into the populated state it is today mainly during the 20th century, a distinctly wet period in the state’s history. Furthermore, the water laws in California are outdated and detrimental to a state experiencing drought. California’s water rights system was created more than a century ago for a state of 3 million residents. Today, California supports close to 39 million people, all in need of water, not to mention the farming industry that requires even more. California law created a “first in time, first in right” system, meaning that people who secured their water rights first obtained priority over future water claimants. These laws allow more than 4,000 companies, farms, and others to use unmonitored amounts of water for free, which has been noted during recent studies on drought-prevention methods. This honor system does not serve a large, growing population in a time of drought as well as it did a relatively small population during a time of steady water supply.

As the state was settled, water was used to irrigate traditionally desert areas into green suburban landscapes, and California became as one farmer puts it “the breadbasket of the world.” From the mid-1970s to the late 1990s the population of California surged by at least fifty percent. Dr. Stine says that, “we consider the last 150 years or so to be normal. But you don’t have to go back very far at all to find much drier decades, and much drier centuries.” It is possible that California’s water infrastructure and entire society in a wet climate that was perceived as California’s normal pattern, but which was actually only a moment in a cycle of drier times.

However, it is notable that drought has become the norm rather than the exception in California’s more recent history. Record high temperatures in California exacerbated the drought throughout 2015 and into 2016. High temperatures cause more evaporation and reduce snowpack. A 2009 survey suggested that the Sierra Snowpack was at two-thirds of normal. There is less groundwater easily accessible in California and farmers in places like the San Fernando Valley have taken to digging wells. The wells pull up what little groundwater remains, with detrimental results, such as sinkholes. Outdated water laws exacerbate these problems.

Groups like the California Department of Water Resources and the Santa Ana Watershed Project are working to analyze the potential effects of a drier California, and how to control the use of water during droughts and even megadroughts. Jay R. Lund, a researcher and teacher at UC Davis, ran a study on the economic effects of a 72-year drought in California. He said, "I was actually surprised at how well we’d get through such a drought. California would not dry up and blow away. It would be bad but we would still have civilization, so long as we managed it at all well.”