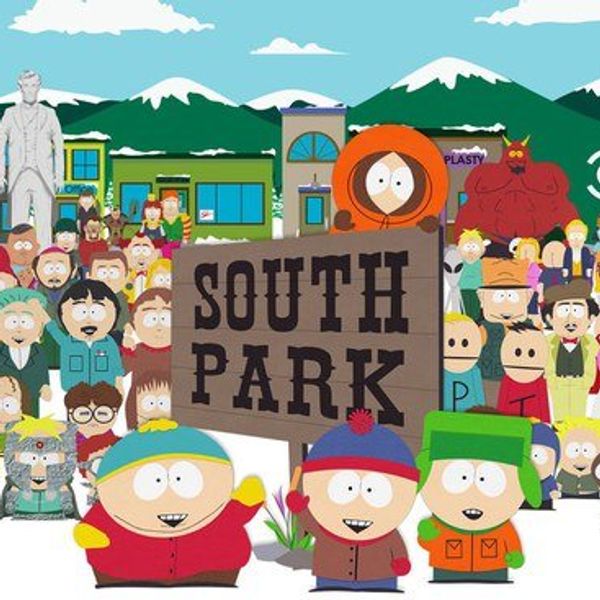

Recently, Al Jazeera published an opinion piece criticizing South Park for—no surprise—being offensive. In this case, the author found Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s satire of the politically correct movement less than agreeable; he attacks the comparison the show makes between the new PC principal—a play-on-words of PC principle I discovered upon revision—and the American police, particularly in regards to the over-zealous tactics used on perpetrators, saying “the juxtaposition nevertheless makes the writers of ‘South Park’ look small-minded and foolish.”

Now, I’ll admit; the author does make some good points; there is, without a doubt, a crisis in American policing tactics that seems to cross the line into human rights violations; however, protecting the overly politically correct does a disservice to society.

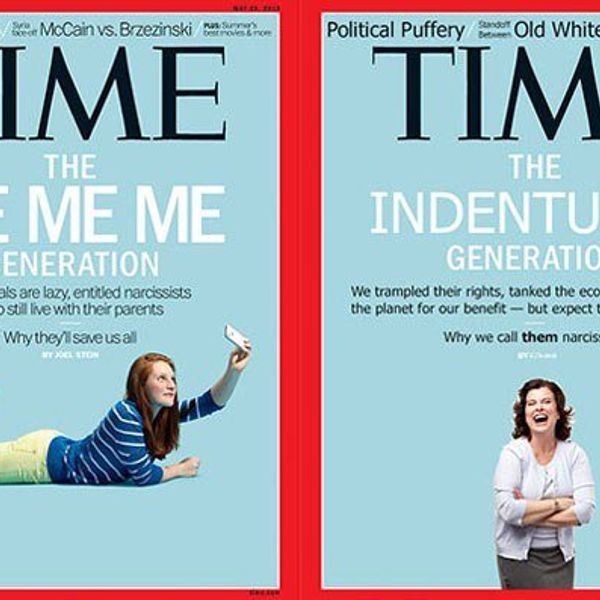

Now to be clear, this is not an essay endorsing malicious racial hatred or bigotry, but instead a call for introspection, perhaps, an analysis of what we as a society are doing in terms of our political correctness policing. Just as we are seeing a rise in a demand for a policing of the police, we too must demand a policing of the PC police.

The dangers of overt political correctness were explored as far back as the 1950s. I’m referring specifically to Ray Bradbury’s dystopian novel, Fahrenheit 451. In the new American society of the novel, morals have decayed, television is king, firemen start fires instead of putting them out, and the ultimate goal of society is happiness. The new America of the novel is multicultural, just like today, and to ensure the happiness of all groups, firemen burn anything that causes discomfort. “Our civilization is so vast that we can’t have our minorities upset and stirred. . . . Colored people don’t like Little Black Sambo. Burn it. White people don’t feel good about Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Burn it.”

You’ll notice Beatty, the fire marshal who speaks that last line, uses the word “minorities” but whites and blacks are cited as examples, implying all races will be equally marginalized by each other. We haven't reached that stage in society yet, but every group has a stain on their records they'd rather keep buried. It'd be nice to simply forget things like slavery or genocide, but we can't and we shouldn't.

The concept of destroying anything somewhat offensive prevails today. Take for example, the recent uproar over culturally appropriative Halloween costumes on college campuses.

In 451, trying to prevent discomfort, caused by discrimination, led to a totalitarian state. And in this state, firemen basically became the PC police, burning anything that might offend anyone else.

So there lies the issue: what do we do with offensive material? Slavoj Žižek, a Slovenian philosopher and creative mind behind A perverts Guide to Ideology, advocates the use of dirty jokes—meaning all things politically incorrect—to create a “wonderful sense of obscene solidarity.”

And that’s exactly what South Park does: it criticizes every facet of society; nothing is off-limits. We need South Park to remind us our stupidity, when we’ve taken things to far or when we just didn’t listen.

Perhaps we all need a dose of reality when it comes to our lives. There’s a degree of pathetic self-indulgence that accompanies being so easily offended; by taking offense instead of laughing at the stupidity and self-deprecating humor, we allow the hateful words to have power over us. A true demonstration of strength does not allow jokes and silliness to demolish it; a true demonstration of strength laughs along with it.

That’s the circle of ridicule: he criticizes them, I criticize him, and now readers will criticize me for writing this piece. It’s only human nature. And since I can’t hire Butters to sift through all the negative comments so I can only see the good ones, I’ll simply ignore the comments and carry on with my own business knowing everyone has their own opinions and opinions are just like assholes: everyone has one, and they stink.