After a long hiatus, here is article no. 3 in my series on Buddhism. In the last two, we learned about poisons of our souls and how we might overcome such vices. In this edition, we will look at the Buddhist view of the Universe.

When you speak of a Buddhist view to the Universe, you must look at two models. For Buddhists, there is a difference in physical and existential geography. The physical explanation puts our Earth as one of four worlds in perpetual ocean. The existential explanation shows that humans are but one of six existential realms.

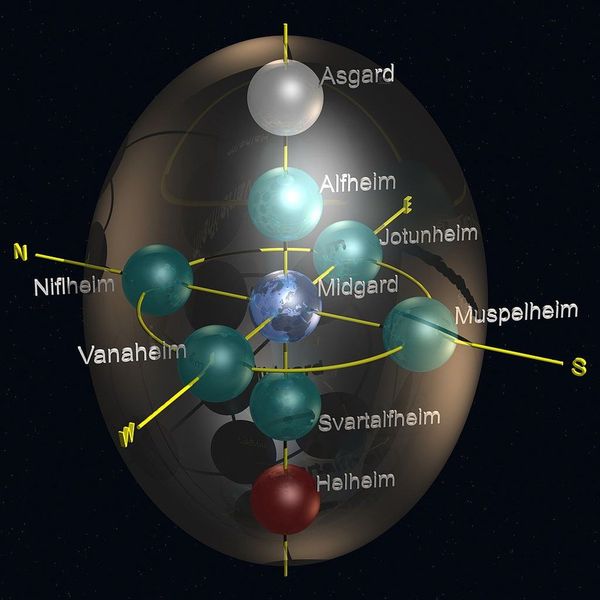

The physical map of the Universe looks like this:

At the center of the Universe is the king of mountains called the Rigyel Lhuenpo; surrounding that are the seven golden hills (Se-ri-duen.) It is unclear from the 2D nature of the image attached, but there is a relation between the heights of those seven hills to each other and to the Rigyel Lhuenpo. The first golden hill is half the height of the Rigyel Lhuenpo. The second hill is half the first and so on, giving rise to a Pareto-Concept type relationship.

Rigyel Lhuenpo is occupied by the beings of the realm of Lha (discussed below) and the figure in the middle with white skin and more than one head is lha Tsangpa, the king of this realm. Fascinatingly, he appears as a being in the Samsara (and therefore being subject to his eventual demise and time in Hell) in Buddhist myth but appears as Brahma, the creator god in Hinduism (not the creator in Buddhist myth.)

Beyond the last golden hill lies the Pchyi Gyamtsho (Outer Ocean), which is bounded. Floating in this ocean are the four worlds (East, West, North and South of the Rigyel) and eight continents (two each in NE, NW, SE and SW.) We inhabit the Southern world called the Dzambuling that is shaped like a horse cart.

Buddhists hold a very pragmatic answer to the question of why the Universe exists and why it began. It was born by the virtue of all that would come to inhabit it. With this virtue, first there was nothing and then came air, then fire, then water in the form of the great ocean and lastly, from continuous tremors, the Rigyel Lhuenpo and others.

This holds a similarity to the Standard Model of Physics and the Big Bang theory where, out of the primordial atom a big bang caused matter, energy and others to be thrown into space. These particles then combine in specific ways to firstly form Hydrogen, then stars and from them other elements and compounds (water being one) and then the planet itself.

But this physical explanation of the Universe isn't as central to the philosophy of Buddhism as is that of the existential universe. This explanation, called the Samsara portrays the different realms of existence and the Nirvana.

Image Credit

We start by looking at the circle. This circle represents the infinite struggle of dukha (suffering) in every form of life. If one achieves Buddhahood, they leave this circle behind and join Nirvana--the space outside the circle. The two Buddhas on top right and left represent this. The beast that holds the wheel is a metaphor that which equals us all - death.

The first circle from the outside is called Tendrel Chunyi and represent 12 scenes out of normal life that keep us from overcoming the Samsara. The details of this are beyond the scope and modesty of this article but as one can see right by the left leg of the beast, there is sex involved. The innermost circle shows three animals--a pig, a snake and a rooster representing three poisons of the soul. The rooster represents desire, the snake, anger and the pig, ignorance. They symbolize the root cause of our inability to leave the samsara --our vices. Surrounding that is the circle showing passage in the intermediate state.

The main circle itself shows the six realms of existence each with their own set of sufferings and their own guiding Buddha. These Buddhas are teachers who have dedicated themselves to helping every sentient being out of the samsara and out of their realms.

The six realms are divided into top and bottom. The three top realms are that of the Lha, Lhamoen and Humans. In most literature, in what can only be called cultural appropriation, Lha has been made equivalent to God. This is false not only for the fact that the idea of God as an omnipresent, all powerful being doesn't apply to Lha's, who are themselves subject to the troubles of the Samsara; but also because Buddhism is an atheistic doctrine where even the Buddha himself is just a teacher.

The Lha's though, still have great power. They have access to the Jangchup Shing - the tree of wish-fulfillment and can it for anything. From living in the luxury granted by that tree, they fail to recognize and appreciate the value of Dharma and the need to be rid of Samsara. This, combined with their predictive powers which tells them toward the end of their lives, that they will go to Hell, cause the Lha's great suffering.

To the left of the Lhas are the Lhamoens. The Jangchup Shing which grants so much to the Lhas has its root in the Lhamoen realm. For this reason, they are overcome by anger and jealousy and seek to wage continuous war against the more powerful Lhas. Of course, these wars combined with the eventual visit to Hell because of their sins, causes them great suffering.

To the right of the Lhas are us, humans. We're the only realm where Dharma has spread and therefore are the only being that can practice it to achieve Nirvana. But of course, even here, we have the suffering of Ke-Ga-Na-Chi (Birth-Aging-Illness-Death.)

The bottom realms have greater sufferings than the top. The three realms of Nyelwa (hell), Yidag (Hungry Ghosts) and Duedro (animals) are reserved for those who have committed great sins in life as humans. Hell, is more diverse than Dante's. Here, there are eight different levels of hot, eight different levels of cold, and two other chambers that are slightly too complicated to explain in a few words.

To the left of Hell is the realm of Yidags reserved for the greedy among us. These beings have stomachs the size of mountains and throats the size of needle heads; this punishes them for glutton, greed and being a miser (frugality is fine.) By their anatomy, Yidags face great suffering from hunger and thirst.

To the right of Hell is the realm of animals (as this suggests, Samsara isn't a physical plane but rather a taxonomy of life forms.) Here all animals suffer from the fear of being eaten, being used and being abused by each other and by humans. All realms but humans (and some Lhas - because Buddha once preached there), have no access to Dharma and therefore are not aware of their condition to remain in the Samsara. A not-so-subtle hint that humans are superior to other forms and that life must be valued likewise!

That, I, knowing very little of Buddhism, try to explain and popularize some aspects of it, is not an attempt at being a charlatan but rather to spread the little I know to as many as possible. After all, even merit as small as a drop of water is equally potent in the infinite ocean of virtue of every sentient being. And my prayers are that if I am to gain any spiritual merit by spreading a few ideas of Dharma, let that merit be shared infinitely through the universe and let it benefit every sentient being, to whom we must look with the same love as we look at our parents.