Content Warning: discussion of specific instances of sexual assault and gang rape, violence as a public health issue, minority oppression, lack of safety and victim blaming.

Unfortunately, what happened between Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh and researcher and college professor Christine Blasey Ford isn't something that hasn't happened countless times before. Through the #MeToo era and simply being someone who knows women, who experience sexual violence the most, we all know a survivor — and if no assault of someone in your life has come to your attention, you should probably evaluate why that is and how you can become a better ally.

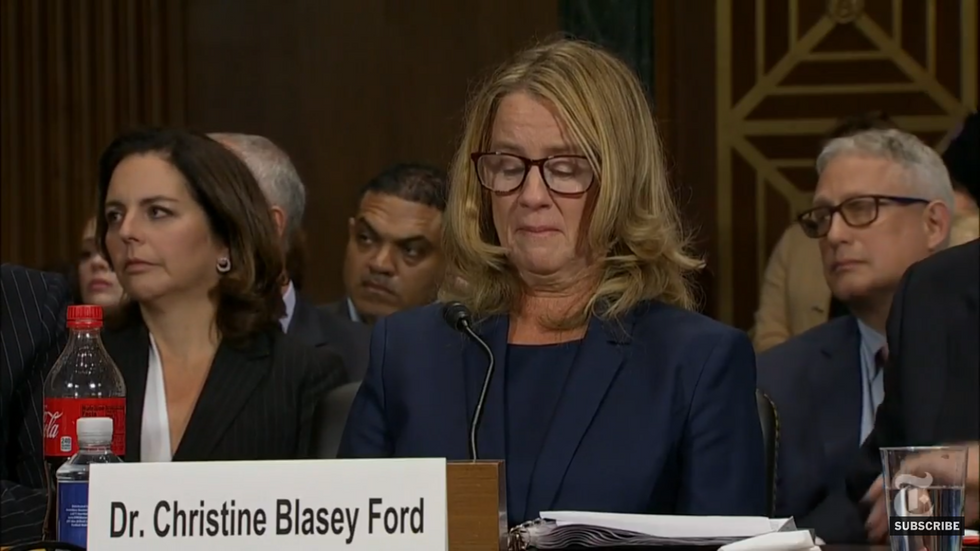

Here are the facts: Ford claims that in high school, Kavanaugh forcibly tried to take her clothes off, groped her and covered her mouth when she tried to scream. Kavanaugh, on the other hand, denies these claims.

Before you begin to make judgments on who you think is telling the truth, let me remind you of an important tweet that explains it all: "Can you name all 59 women who came forward against Cosby? Can you name half of them? Can you name 5? Would you recognize them out of context? Do you want an autograph? Cool, so we agree that women don't make rape accusations to become famous."

Also, I believe it's important for everyone to understand that victim blaming comes from defensive attributions, in which people explain events in a way that helps them feel safer and less scared. Yes, it's easier and more comfortable to think that people are assaulted from "putting themselves in that position" — but this thought is a way we keep our minds safe rather than put a reason to an event that could quite literally happen to anyone. Violence is a public health issue: even if you do all of the "right things," like self-defense classes, and even if you're lucky enough that your body naturally responds in a fight or flight way rather than a freeze way, unlike most survivors, the violence you potentially avoided will occur to someone else.

It's scary to think that we have just as likely a chance of being assaulted — so we say "if I do this, then I'll be safe." I hate to say it, but that's not really the case. We aren't in control of everything that will happen to us. We may protect ourselves here and there, but that won't save us from everything. At the same time, we can't allow ourselves to walk around in fear or on eggshells all of the time. We have to live our lives.

For those who argue she should've reported sooner, please understand that only about ⅓ of sexually violent acts are reported and that statistics in which people are truly falsely accused are minuscule and the same across multiple kinds of crimes — not more so for sexual assault cases. If people do take time to decide they want to report, they have several valid reasons why. For example, the process takes years and over 99 percent of perpetrators go free, survivors may become publicly shamed by people who are on the perpetrator's side, they fear not being believed or being victim-blamed, they may feel shame over what happened to them or blame themselves, and they may feel invalidated because they don't fit the "perfect victim" stereotype.

Unfortunately, not enough people understand the truth about sexual assault situations; unfortunately, the justice system doesn't always sustain justice and investigators can sometimes be just as ignorant as the public. And frankly, with how badly Dr. Ford has been crucified over simply speaking up, why would any survivor want to report? She has everything to lose -- in which she has lost much -- and has nothing to gain, especially that's worth a loss of this caliber.

If we can understand why it might take people some time to be open about other problems they're dealing with, why is our standard for sexual assault so different?

In addition, people may dissociate or freeze (fight and flight are not the only options), which are ways the brain protects itself. These factors can contribute to survivors "changing their story" or not knowing all of the details, which are often misinterpreted as "lying" or "making the story up." Survivors may also continue to interact with their assaulter because they fear conflict or retaliation by "changing the status quo," because they potentially blame themselves or because their job depends on it.

Minorities are especially oppressed in reporting and safety. For example, survivors who identify as LGBTQIA+ may fear to report against their partner because they don't want to further the incorrect stereotype that "LGBTQIA+ people are weird/gross/wrong" or be shunned by others in the community who are on the side of their partner or assaulter. People of color may not want to report against a perpetrator of color because it could further the incorrect stereotype that "all black men are violent." People who live in a country illegally may have to put up with the abuse or assault they endure without reporting because they could be deported back to their unsafe homelands. No matter people's different opinions on immigration, how can we not acknowledge the fact that those survivors deserve safety and justice as human beings?

In addition, looking at this case and how we can better our society's understanding and bystander intervention, we would be remiss to not discuss Mark Judge's role in this case. Ford claims that Mark Judge, one of Kavanaugh's classmates, was in the room with her when Kavanaugh was assaulting her. He laughed and played loud music so no one would hear the assault. This situation does mirror some of his past words and actions, such as when he discussed a time when he took turns with other guys having sex with an intoxicated girl. In other words, gang raping her. Actions and statements like these cannot be excused. Regardless of any aspect of the girl, what he admitted to doing was wrong.

In Kavanaugh's assault against Ford, Judge isn't blameless. Similar to bullying prevention discussed in middle school, if you're not helping, you're hurting. We must be active bystanders. One Act, an organization that promotes bystander intervention, trains people on how to be active bystanders and provides multiple avenues for people to prevent violence in simple and less intimidating or confrontational ways. For example, if someone seems uncomfortable, act like you're great friends who haven't seen each other in a while and want to go hang out. Cause a distraction. Bring friends along with you so you don't feel like you're trying to intervene on potential violence alone.

One more thing: if you don't stand with the survivor, you're standing with the perpetrator. And young children are watching you, learning from you are teaching them through your actions and words. Be mindful about the messages you're sending them and how they compare with what messages we need to be sending them. What are you teaching the next generation? What are you teaching the survivors in your life who are terrified to reach out for support?

And, because I can't help myself... women are always too emotional to be in politics? Oh, okay. Ha.