Why is the Christian Church in the United States so divided? Why, for example, do we have numerous denominations across the country? Why do we have "conservative" and "liberal" interpretations of the Bible? What caused this rift? Through the failure of church leadership to address the rising religious tensions in America, they inadvertently created a religious divide that continues in present-day America.

This is a three-part study. The first part will cover the arrival of the Puritans and their effects on religious life in the early American colonies. The second and third parts will cover the First and Second Great Awakenings, reviewing the ideas put forth and the denominations created that still affect America today.

Puritan Settlement in North America, 1620-1630

In 1620, Christian settlers known as Puritans arrived in Cape Cod in present-day Massachusetts. After disagreements with the state-endorsed Church of England led to religious persecution of the Puritans, they secured charters from the King of England granting them the right to settle in the New World. In September 1620, they landed in Massachusetts, where they established a Plymouth Colony. Later, in 1630, more English Puritans arrived in the region, establishing Massachusetts Bay Colony. These colonies would become leading figures in early American political life, dominating New England politics until the mid-1680s.

Puritan Religious and Political Beliefs

Puritans were Protestants and believed that by faith in the Word of Jesus Christ alone man could achieve salvation. They also held to the beliefs of John Calvin, who asserted that God elected from the masses those who would enter into Heaven and who would not. They also adhered to belief in the "Original Sin" in which man remained in a state of sinfulness since the fall of Adam and Eve.

Their politics were heavily influenced by their religious beliefs. Thus, they decreed that to have full citizenship, all residents had to be members of their community's church. To the Puritans, becoming member of the church meant that one had to have a "conversion experience" and afterwards be baptized. A "conversion experience" occurred when an individual did and experienced three things: 1) the convert first began to introspect and identify his sins, beginning to pray and read the Bible; 2) recognize his inability to erase his sin and that his good deeds would not save him; 3) realize that Christ alone could atone for his sins, whereupon the convert would finally receive Christ and become righteous through Him. Their other laws were very socially conservative. Adultery, theft, dishonoring one's parents, arson, witchcraft, and lying were all legally punishable by death, though death penalties were rarely executed.

Disputes in the Colonies

Because the Puritan colonies consisted of bodies of people who broke from a state religion in England, it was inevitable that some colonists would not agree with the same structure in American settlements. One such individual was a man named Roger Williams. Williams was a devoted Puritan who had moved back and forth between Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay, and he disagreed with the enmeshed relationship the church had with the governments of each. Rather than make laws based on the views of the church, the government should make laws protecting the people's rights, including that of the right to believe as they chose, not just the colony's religion. He also did not like the manner in which the Puritans had acquired their land. Grants from the King of England had given them a "right" to the land, but it did not consider how Native Americans would be affected. The land acquired by the colonial leaders was taken from Native Americans, and Williams believed this legally and morally wrong. In 1636, the Massachusetts Bay authorities banished him, and he traveled to Rhode Island, buying the property from the Native Americans, and in 1640, he established the Colony of Rhode Island governed by the principles he believed in, advertising it to all who felt oppressed in the Puritan colonies.

Yet another upheaval arose in 1656-1660, when members of the Society of Friends, more commonly known as Quakers, began preaching in Massachusetts Bay. A Christian-influenced cult that originated in England, Quakers believed that every individual had the "Inner light" of God within them. Through silence and meditation, they asserted, God's light would shine through them and communicate His will to them. When itinerate Quakers traveled to North America to grow their religion, they were not received well by the Puritans, who executed them. News of this treatment reached England, and in 1661 King Charles II, with whom some influential Quakers were in good standing, revoked the charter of Massachusetts Bay and sent a royal governor to ensure that no more Quakers were harmed. In 1677 and 1681, prominent English Quaker William Penn acquired land grants for West Jersey and Pennsylvania, respectively, creating havens for Quakers. These colonies took example from Rhode Island and promoted religious freedom.

These internal conflicts made it difficult for the colonial leaders to maintain their hold on their regions. Religion had been an integral part of life in Puritan society: political and community functions all had had something to do with the church. But the disagreements served to decrease the appeal of Puritan Christianity among the younger generations, who now had more colonies to look to, ones that promoted different faiths and offered the religious freedom. The Puritan leaders knew they had to respond before this threat grew larger.

Educational Decrees

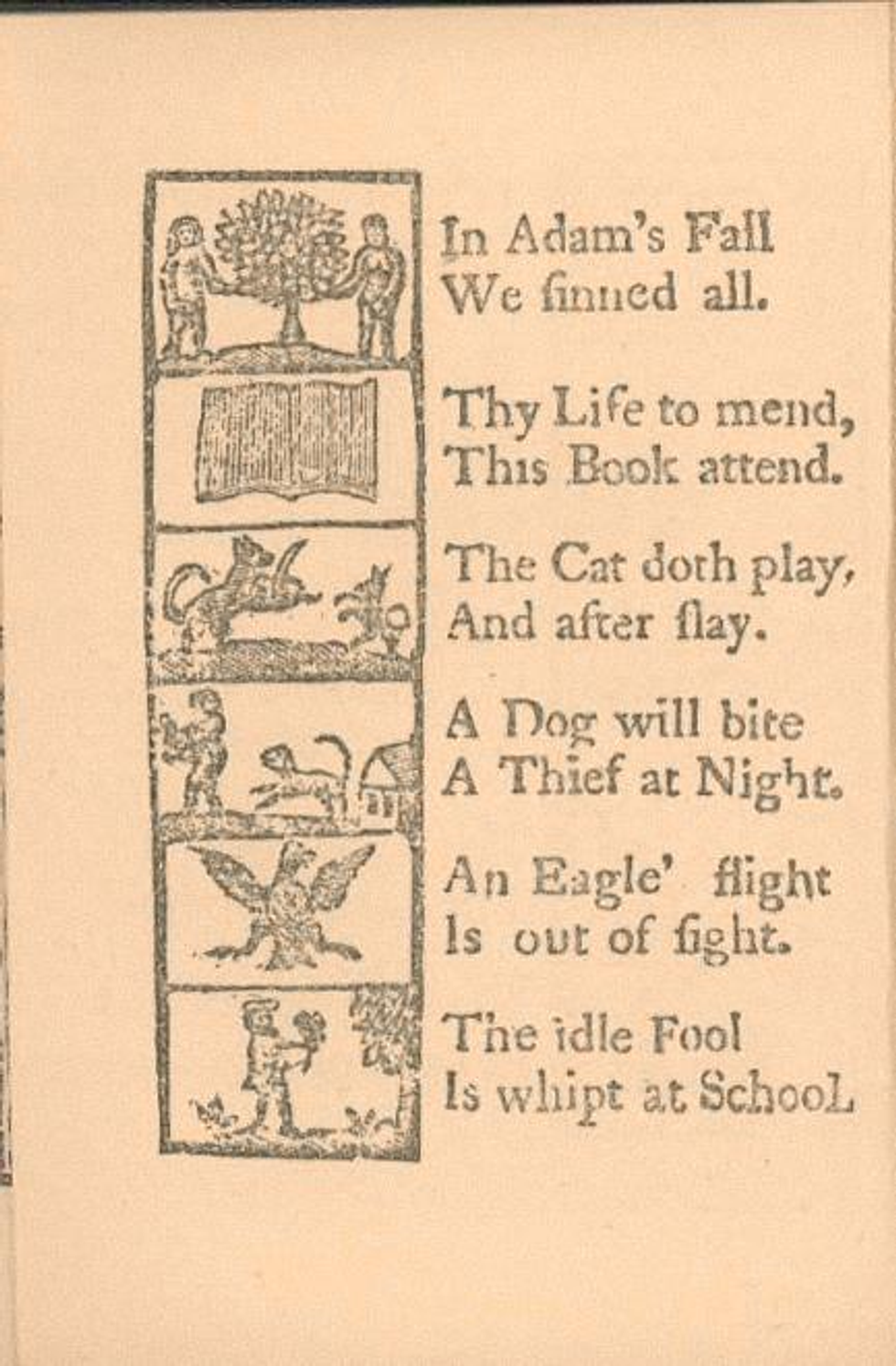

Their response was simple: target the youngest generation, requiring religious education in their colonies. They created public education systems intended to give children a Puritan education. In this respect, the leaders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony led the way, creating Harvard College in 1636 to raise ministers for the Church. Later, they created grammar schools through the Massachusetts School Laws of 1642, 1647, and 1648. These laws also created a board of selectmen to oversee the schools. These schools were meant to teach children about the Bible and the Puritan faith, using a standard textbook called the New England Primer. This primer contained an alphabet for younger children to learn, catechisms, and Puritan proverbs meant to ensure they were not ignorant of the Scriptures.

The "Halfway Covenant"

Despite their efforts, however, it became clear as the original Puritan settlers grew older that the newer generations were less spiritually-oriented than their fathers and grandfathers. As their children grew up, they did not have the "conversion experience" of their parents, hence, they could not be baptized. This unfortunately meant that the new generations could not become church members, which kept them from participating in their community or government. The leaders realized that in order for their colonies to continue, their offspring would have to be allowed to become members of the Church. And so, from 1654 onward, churches adopted a practice which they called "Large Congregationalism." Derided by opponents who called it the "Halfway Covenant," it allowed non-Christians to become members of the Church through baptism, but they could not participate in church functions. And so, while not generally considered "full" members, they were able to participate in Puritan society.

This acceptance of non-Christians in the church only served to split the church into factions: conservative factions who were against non-Christian participation in the church, and liberal factions who accepted the non-Christians. Out of the liberal factions sprung "Unitarian" theology, which, hoping to be more inclusive of nonbelievers, rejected the Christian belief in the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, instead believing in a one-personed God. And while religious conservatives believed that God would condemn all who did not believe in God to hell, Unitarians believed that mankind was not inherently sinful and thus too good for God to punish them. Unitarians were also quick to reject the idea of predestination, arguing that God did not "elect" individuals to enter Heaven with Him. Conservatives fought the liberalism in the church, but because the younger generations found the Unitarian rejection of retribution for sin more appealing than the constant reminder of man's sinfulness by conservative preachers, the liberals seemingly won out. By c. 1700, more than three-fourths of the American colonies' churches were Unitarian.

Conclusion

The inability of the New England Puritans to adequately address the rising religious conflict caused a serious rift among the Christian population. The influence of Unitarianism would grow strong during the period before the First Great Awakening, however, a small group of Christian laymen began to share the gospel with the colonists, paving the way for revival in the 1730s.