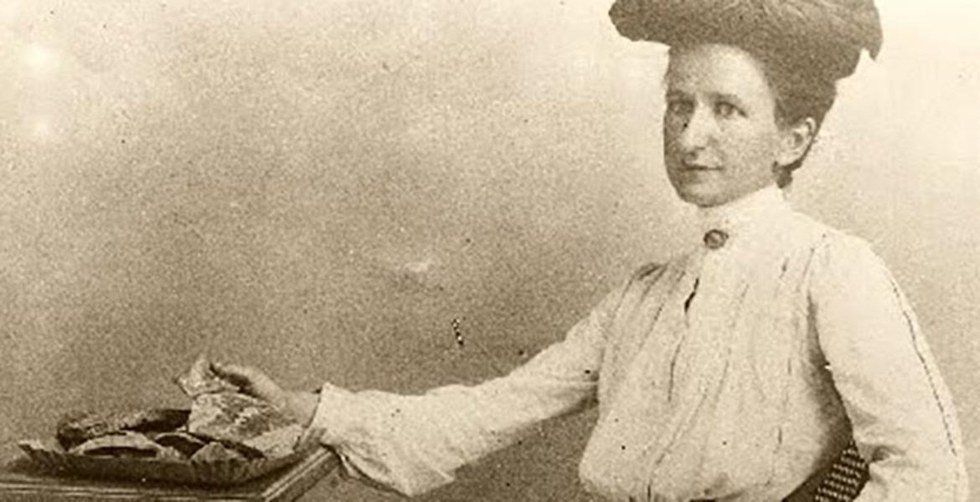

Harriet Boyd had just received a prestigious grant from the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, and was finally going to be able to work on an archaeological excavation. The project she had chosen was the American excavation at Corinth, but when she wrote to inquire about a job their response was not as she had hoped. They told her that Corinth “did not afford enough material for women.” Young Harriet was not concerned. If she couldn’t work for a project, she might as well start her own.

Boyd was born in Boston on October 11, 1871. She was the youngest of four children raised by their father after the untimely death of their mother. She relocated to Northampton, MA in order to attend Smith College, one of the Seven Sisters colleges that had been recently established in the northeastern United States for the purpose of educating young women. At Smith, Boyd studied the Classics, but was not satisfied with the classroom environment. She soon headed to Athens hoping to continue her education in a hands-on way.

Boyd enrolled in the American School of Classical Studies in Athens in 1896, but as Crete rose against their Turkish occupiers and war broke out near Thessaly, much of her time was spent working as a nurse for the Red Cross. By 1899 the situation had calmed, and Boyd won the Agnes Hoppin Fellowship, giving her the opportunity to pursue fieldwork. After the denial from Corinth, Boyd headed south to Crete.

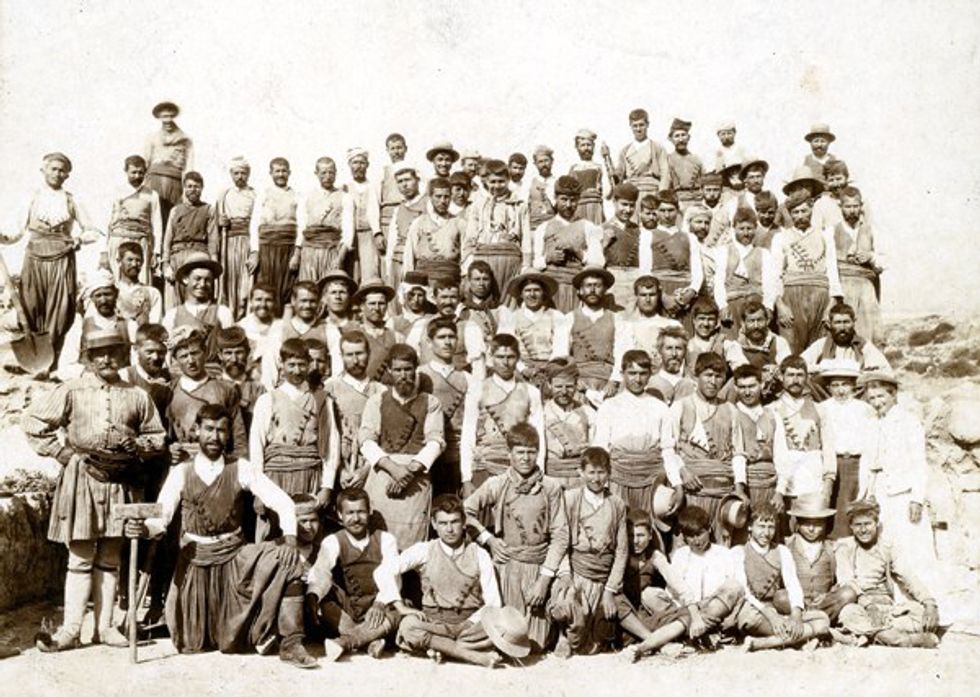

Her first stop was the Minoan site of Knossos, where Sir Arthur Evans was leading the excavations at the site thought to be the location of the mythical labyrinth from the story of Theseus and the Minotaur. Boyd arrived just in time to witness the uncovering of one of the most famous Knossian discoveries, the “throne room.” While there she was able to spend time with Evans, who encouraged her to pursue her aspirations, and told her to begin her search for a new site in the Kavousi region. Boyd became acquainted with a Greek man named Aristides. They traveled through Kavousi together and he helped her communicate with the local people. They showed her artifacts they had picked up, and more importantly the remains of ancient walls. She obtained permission to dig as a representative of the American School from the Cretan government, and spent three weeks during the summer of 1900 excavating at various small sites. She took all of her finds to the Heraklion museum and spent the rest of the summer cleaning and studying them.

By this time Boyd had returned to Smith College as a lecturer, but continued to spend her summers in Greece. The following year she became the first woman to present a lecture for the Archaeological Institute of America when she presented her Kavousi findings. The talk convinced the institute to fund the continuation of her work in Crete. When she returned that summer a man named Giorgos Perakis from the town of Vasiliki showed her the remains of a Minoan town called Gournia. She began digging immediately, and was greeted with immense success. In the first summer, they found a double axe and a goddess figurine, two iconic symbols of Minoan civilization. By the end of the season Gournia had been called “the site best worth visiting in Crete” by the London Times.

Boyd returned to Gournia for two more excavation seasons in 1903 and 1904. In 1903 she added to her list of incredible finds with an octopus decorated stirrup jar. The success of her work gained her worldwide fame, which increased even further when she received permission from Crete to send her finds back to the States. Many of these objects remain in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, and the Penn Museum today.

In 1905 Boyd returned to Crete, but spent the summer working in the Heraklion museum rather than in the field. It was during this time that she became reaquainted with an English anthropologist named Charles Henry Hawes who had been traveling the world doing ethnographic research. By the end of the summer the two were engaged. In 1908 Harriet Boyd Hawes published her first work, a massive tome entitled “Gournia, Vasiliki and Other Prehistoric Sites on the Isthmus of Hierapetra.” The following year she and her husband co-published “Crete the Forerunner of Greece.”

After the publications were released Boyd Hawes’ academic life came to a rest. She and Henry had children and established their life as a family. Being the woman that she was, this did not last long. War had again broken out in the Balkans and she returned to lend her skills as a nurse. Not long after Europe was changed forever with the outbreak of World War I, and Boyd Hawes’ moved to Paris to provide more relief.

When the war ended she returned to Massachusetts and began teaching Ancient Art at Wellesley College, another of the Seven Sisters, in 1920. She and Henry retired to a farm in Virginia in 1936. She used this proximity to Washington D.C. to her advantage a few years later when she was able to secure a luncheon with Eleanor Roosevelt. Europe was on the brink of a second world war, and Boyd Hawes insisted to the First Lady that it would be immoral for the United States to remain neutral. She also took the opportunity to speak against imperialism.

Harriet Boyd Hawes passed away in Washington D.C. on March 31 1945.

If you are interested in learning more about Harriet I recommend the biography written by her daughter Mary Allsebrook, “Born to Rebel: The Life of Harriet Boyd Hawes.”

For more information on Gournia and the recent excavations at the site please visit www.gournia.org

The artifacts sent to American museums by Harriet in 1904 can be viewed on the websites of the Met, the MFA, and the Penn Museum.