In 1976, Emma DeGraffenreid and several other black women sued General Motors for discrimination. Alleging that the companies industrial policies discriminated against black women. The issue which the court was left to deal with was figuring out whether or not the plaintiffs were seeking relief from racial discrimination, or sex-based discrimination.

This lawsuit attempted to combine two causes of action into a new special subcategory. A new category request which the court greeted with sheer unacceptance. The court noted in its weak attempt to deal with the case at hand, that the plaintiffs failed to cite any prior decisions which have stated that black women are a “special class” to be protected from discrimination. Due to the fact that not all blacks were being excluded, and not all women were being excluded, the black female plaintiffs did not have a case to make. Apparently just because something does not hold precedent, it is not possible.

If anything, this case served to show the compounded discrimination that women of color face by being both of color, and women. It was also during this time that the frequently thrown around term “intersectionality”, became coined by Kimberle Crenshaw, the creator of Intersectionality theory. Crenshaw is a professor of law at UCLA and Columbia University, and an expert in the field of Civil Rights, Black Feminist Theory, and Racism & The Law.

Intersectional feminism is a type of feminism that looks at how women of different backgrounds experience oppression. We experience discrimination, benefits, and life in general, based on a number of different identities that we have. Feminism that does not take into account all of the different subgroups of women - young women, old women, poor women, colored women, muslim women, disabled women, bisexual women, lesbian women, asexual women, trans women, women with mental illnesses, women with diverse body types - is not feminism at all.

Women face discrimination first hand due to gender, and second hand due to all of the other subgroups that they may fall into. Most notably, is the intersection of race, which Crenshaw has devoted much of her academic career stressing. Women of color have race discrimination coming from one direction, and gender discrimination coming from another. These discriminations end up colliding in ways that we cannot anticipate, or understand. Case in point, is the DeGraffenreid v. General Motors case.

In addition to the now frequent identification of intersectional feminism, there is also another kind of feminism which has gained much scrutiny since last week’s women’s march - white feminism. What is white feminism ? In short, feminism that ignores intersectionality. It is crucial to note that not all feminists who are white, are white feminists. Of comparable importance, it is neither a requirement to be white in order to be a white feminist. People often advocate in contrast to their own self interests either due to being uneducated, or because it is the only outlet that currently exists.

This is where the problem lies, with the stagnant face that feminism has had. In addition, calling a theory that is meant to be inclusive due to its very nature (the advocacy of women's rights on the basis of the equality of the sexes) out on their inherent exclusive behavior and or tendencies, is not pulling the race card, either. White feminism exists in a bubble comprised of only white, cisgender, and straight women - all experiences of women who do not fit these categories, are excluded from discussion, i.e., they’re not on the agenda.

White feminism assumes that the way that white women experience misogyny, is analogous or even identical to how all women do. Part of the underlying idea behind such ideologies is that everyone is similarly situated, we are quite clearly not. This is what intersectionality seeks to make transparent - our inherent differences that are made significant not only in the face of the law, but in everyday life. This isn’t about silencing the voices of white women, it’s about opening up dialogue with more diverse voices, and engaging with the experiences of those who have been silenced.

In order to see feminism through an intersectional lens, one must first assess their own privileges. Privileges are the places within society where we hold more power than others, which, in turn, shapes our experiences. Perhaps more important than realizing our experiences in relation to our privileges, we must also become attuned to what our privileges prevent us from experiencing. This is why it is crucial to listen to women who don’t hold privilege. Without this sort of open discourse, many are doomed to be left in the dark, thinking that they are righteously standing up for women’s rights, when really, they’re standing up for their women’s rights.

All I'm really saying is, let's look out for one another as a collective, okay ?

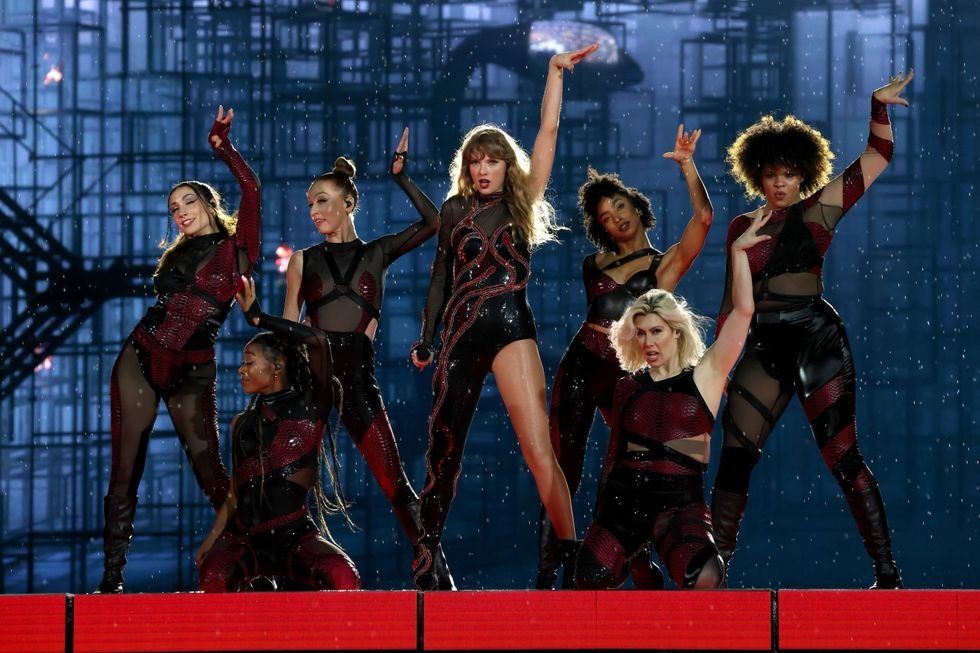

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight.

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight. Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage.

Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage. Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots.

Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots. Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.

Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.