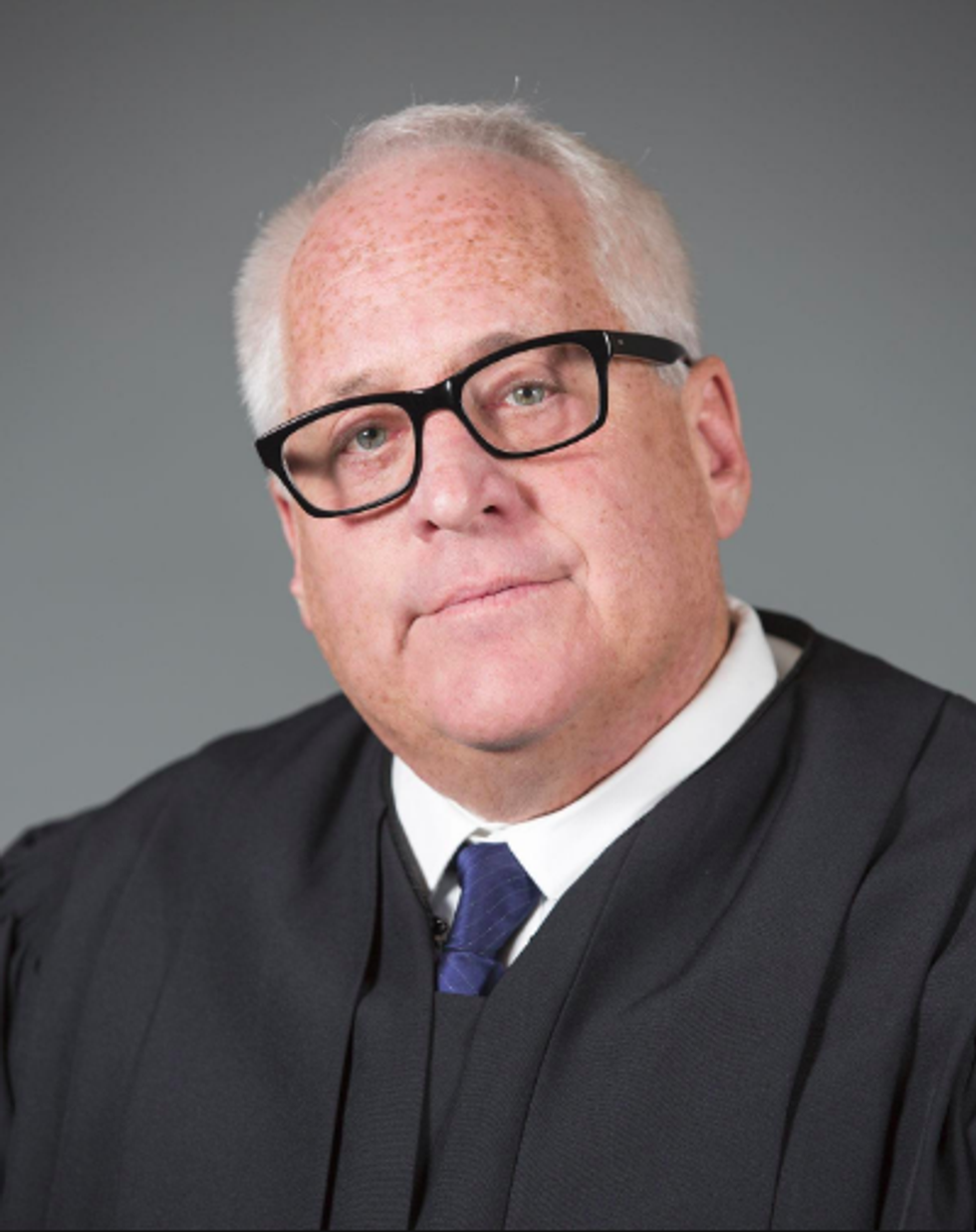

Since I was not chosen to serve on the jury for Kevin Bernell Warrior v. State, I returned to the basement on my third day. After a couple of hours, I was called upstairs again. I'd heard talk that this week was particularly heavy with cases—which was certainly proving true. As before, the other panel members and I lined up alphabetically outside before entering. The courtroom set-up was opposite from the last since it was on the other end of the building, but it was in no way less impressive. To my surprise, I'd been called for yet another first-degree murder case. This time it was Cameron Hendrick versus the State of Oklahoma, Judge LaFortune presiding. LaFortune was the former Tulsa mayor in the early 2000s, and his nephew, G.T. Bynum, is the current mayor.

After Judge LaFortune's introduction, the prosecution explained the basics of the case. The attorney said Mr. Hendrick was convicted of shooting a man outside an east Tulsa apartment, and that the murder had been featured on the true crime TV show "The First 48." The episode, "Bloody Valentine," can be found on Youtube in very poor quality, and we were strictly forbidden from looking it up. (Naturally, the moment I was dismissed from the case at the end of the next day, that was the first thing I did). "I don't have many hard and fast rules," the attorney said, "but this is one of them." To avoid bias, the prosecution asked if any of us had already seen the episode. "I can't give away any details of the case," he said, "but to give you a reminder so you know which one I'm talking about, there is a part where a woman says 'baby daddy, baby daddy, baby daddy.'" A woman raised her hand to say she'd seen it and was promptly excused from the courtroom. No one else had, so the attorney continued explaining the basic facts of the case.

Cameron Hendrick was suspected of shooting and killing his girlfriend's 'baby daddy' Robert Singleton Jr. on February 16, 2015. It appeared that Hendrick became jealous after learning the father of his girlfriend's child would be at her apartment to visit their son. Though Hendrick's girlfriend Brittish Ratliff made it clear Singleton's presence was no indication of an affair, Hendrick saw it differently. He made many calls to Ratliff, then posted a clear threat via Facebook, in which he included a picture of a gun and said he would be coming over to Ratliff's apartment. Hendrick pleaded no contest, which was not surprising considering his girlfriend was a clear witness to the five point-blank shots fired at her child's father.

In their best effort to select an impartial jury, the prosecution wanted to rule out any panel members with intensely one-sided viewpoints regarding the nature of the crime and the subsequent sentencing. The attorney made it clear that this was not a capital case but questioned the panel about their opinions on capital punishment. Several members, including me, raised our hands to indicate our bias against the death penalty. Another fair few raised their hands and expressed that their ruling for against capital punishment would vary from case to case depending on the specific details of the crime. Two men raised their hands, and after further questioning, stated that they would expect capital punishment as the proper sentence for all instances of murder- regardless of the situation. These men were dismissed just like the woman who'd seen the television episode.

The prosecution continued with the voir dire process, calling randomly on members of the panel. Dressed in my business attire before the court, I felt stupidly esteemed when the attorney addressed me with a formal "Miss Van Tassell" before posing his question. He asked whether I knew the definition of 'pre-meditated' in reference to pre-meditated murder. I told him that pre-meditated murder meant the suspect had thought about the situation and formulated a plan to commit the crime rather than committing a murder in the heat of passion. "Very good," he responded. It was nice to be praised for correctly answering such a simple question. But as intelligent as I apparently was, I was not what the prosecution, nor defense, was looking for. Upon my return on the fourth day, I was once again dismissed from the case.

A couple months later, I looked up the results of the case. Hendrick, like Warrior, was sentenced to life without parole. However, unlike the Warrior case, no new evidence had been brought up in the Hendrick case, and nothing would acquit this man of such a heinous crime.

Though I was not chosen for either case, I found my jury duty experience to be incredibly interesting and informative. While the formal setting and level of responsibility might have given me a false sense of importance, the experience gave me the opportunity to observe the inner-workings of an official court case and gave me a new appreciation for the law.