Alright kids! So I had some serious writer’s block and couldn’t decide what to write about, so I flipped a coin to decide. It landed on tails, so now I have to do an article on a serious and relevant topic, so in light of this, I decided to do it on a very controversial topic: race. More specifically, I’ve decided to do it on “blackface,” an act in which white Americans would put on makeup and portray African Americans in various forms of media. The act of blackface helped to perpetuate many stereotypes about African Americans that still exist today. Blackface has a long and foul history, so sit down and buckle up, because we’re going on an adventure through time.

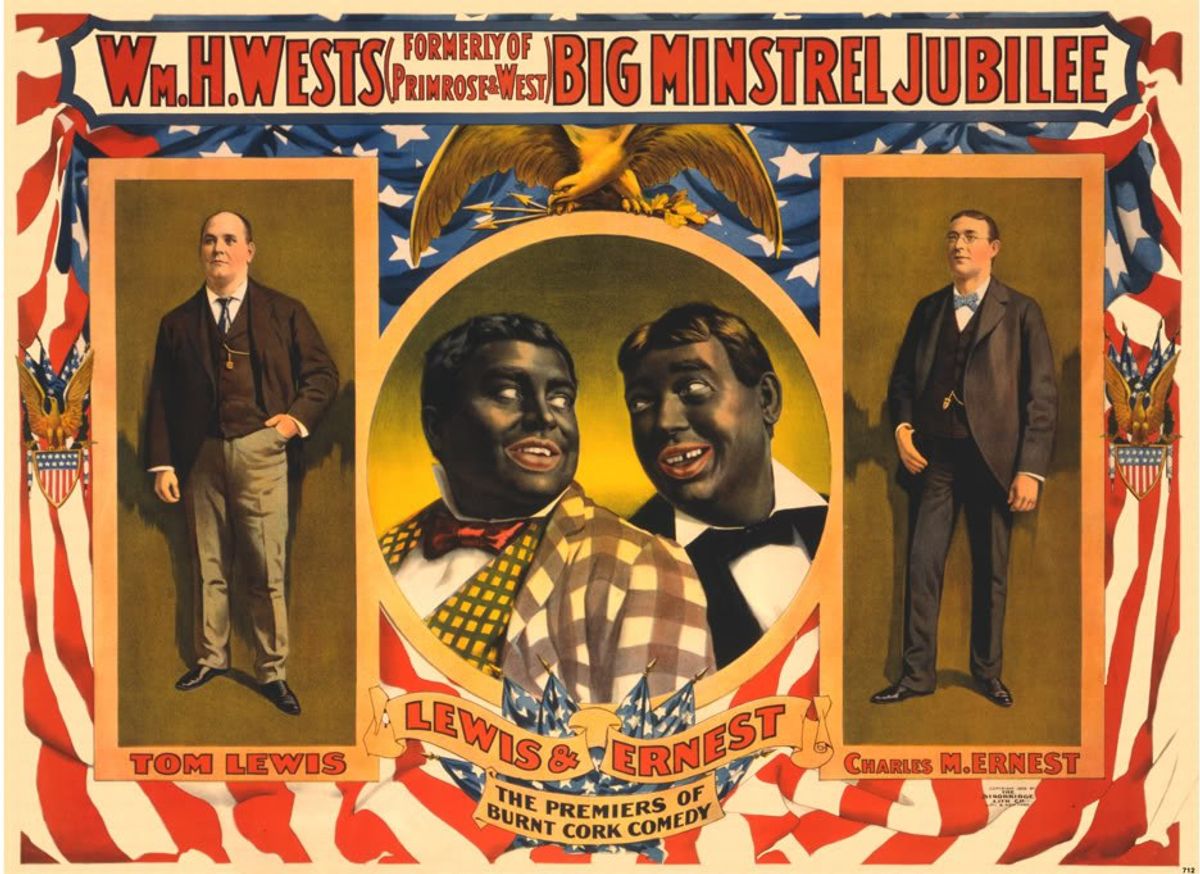

Blackface first began in the 1820s at the start of the era of minstrel shows. Minstrel shows were shows put on by white people wearing blackface and consisted of comedy skits, dancing and music. They usually portrayed blacks as lazy, dim-witted, buffoonish, superstitious and musical. As minstrel shows gained increased popularity over the course of the 19th century, the portrayal of blacks in these shows caused Americans to form distinct stereotypes about African Americans and most people expected blacks to conform to at least one of these stereotypes. These include the “mammy,” the motherly figure who was the core of plantation families; the “dandy,” who was a northern black man who attempted to mimic white, upper-class dress and speech to no avail; and the “Buck,” a large black man who is proud, sometimes menacing, and usually chases after white women. Makeup for blackface usually consisted of a layer of burnt cork over cocoa butter (substituted with black grease paint in later years) and red or white lips painted around their mouths. Costumes were gaudy combinations of formal wear and performers usually spoke in a “plantation” dialect. Entertainment included imitating black music and dance as well as a variety of jokes, skits and songs that were based on stereotypes of black slaves. In early years, minstrel shows were used to romanticize slavery and portrayed slaves as simple and cheerful, always ready to please their master. Overtime, they became a source of cheap entertainment at the expense of black people.

By the start of World War I, minstrel shows had mostly died out, but by then, blackface began to see its way into other forms of media, notably movies. Perhaps one of the most notable acts of blackface in film was D.W. Griffith’s "The Birth of a Nation". The film portrayed African Americans (played by white men wearing blackface) as unintelligent and aggressive towards women. Later, blackface was used by the star of "The Jazz Singer," who portrayed a Jewish performer using blackface to perform jazz songs on stage. Blackface took shape in many other forms over the course of the first half of the 20th century. The radio show Amos ‘n’ Andy, whose popularity resulted in a subsequent television show, saw actors Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll don blackface and speak in exaggerated, stereotypical voice characterizations. Many cartoons during this time, dubbed the “golden age of animation,” featured many of the same racist stereotypes that find their roots in minstrel shows. Walt Disney, for example, released "Fantasia" in 1940 and "Song of the South"in 1946. "Fantasia" had to have several shots cut from "The Pastoral Symphony" due to the fact that these shots featured racist stereotypes while "Song of the South" was flat out called racist due to the poor way it portrayed race relations in the post-Civil War south. Movies, television, and radio all apparently endorsed blackface and poor stereotypes of blacks during this time, with very few efforts beyond protests by the NAACP being made to stop it.

“Okay,” I hear you saying, “but that was then, right? Blackface was a big thing back then, but that isn’t an issue with television now, right?” Well, not exactly. The Civil Rights Movement of the 50s and 60s resulted in blackface in being banned from television, especially after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 eliminated “separate but equal” laws. However, the stereotypes that were created and endorsed by blackface entertainment would have a lasting effect. For example, shows such as "Diff'rent Strokes" and "The Jeffersons" incorporated various stereotypes that were popular during the minstrel era, such as coons and mammies. Also, the 70s saw the rise of a genre of film known as “Blacksploitation” films. Such films often centered on a black anti-hero with a supporting cast consisting of stereotypes of pimps, whores, and criminals and most, if not all, were African American. The antagonists of said shows were usually white cops or politicians who were corrupt and exploited poor black communities. These films received huge backlash from African American community leaders, arguing that they were offensive and were a major reason that blacks were still oppressed during this time, and by 1980 the entire genre had died as a result. But what about today? Well, even today, television and movies still seem to capitalize off of black stereotypes. "The Cleveland Show," for example, has been criticized for pretty much being "Family Guy" in blackface that played on negative black stereotypes for humor. Similarly, Tyler Perry shows and movies are sometimes criticized for utilizing these same stereotypes. Perry’s most famous character, Madea, is based on the “mammy” stereotype, for example. Characters from shows such as "House of Payne" and "Meet the Browns" also incorporate blackface stereotypes.

So we’ve talked about blackface as portrayed on T.V. and movies, but what about in real life? Blackface is a very relevant topic and one of the most controversial. In today’s context, the actual use of blackface is used to mock and belittle African Americans and is seen by most, if not all, people in the black community as one of the highest forms of insults, second probably only to the n-word. But besides the actual act of blackface, the legacy left by it is a major issue today. Remember, minstrel shows back in the 19th and early 20th century gave many whites their first glimpse into black culture and helped set the ground for many of the stereotypes surrounding black culture up to the present day. The “mammy” stereotype, for example, has become the overbearing, strict, no-nonsense maternal figure. Even if some stereotypes have died down, new ones have taken their place. These include stereotypes about gang-bangers, drug addicts, and the ever popular “kid who never knew his dad” stereotype. If you’re black, then you must know at least 3 guys in a gang, you must come from the hood and you just must love rap music. You probably smoke weed, you probably drink Hennessey and you probably stole that watch you’re wearing. These are all stereotypes that can find their roots in the stereotypes that were originally created as a result of blackface.

Look, I know that the issue of race is a touchy subject, but it’s something that needs to be talked about. Blackface is an issue that has left a lasting legacy over the last two centuries. If we ever hope to move forward as a nation and as a species as a whole, we must learn from the mistakes of our ancestors. History doesn’t have to repeat itself if we don’t let it. And so ends our history lesson. I hope we all learned something from this.

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by

Photo by

Photo by