When “Iron Man” dropped in 2008, I remember being floored by the film's quality. It was one of the best films that year. In a year that saw the likes “The Dark Knight,” that’s saying something. In the years that followed, the expanding comic inspired cinematic universes, the MCU as well as the DCEU, most films were plagued by an overreliance of vanilla flavoring. To be more precise, a lack of diversity.

“But Andy, there are people of color in recent comic book films,” says a fictitiously disagreeable person.

“Yeah,” I fictitiously respond, “but there’s how many people of color versus people not of color?”

Imaginary argument aside, there are people of color within comic book films, some really awesome ones, too. There’s just not that many. There are even fewer comic book films that elevate people of color from supporting characters to the leads and that weren’t poorly executed or deliberate farces.

That all changed, however, with the recent release of Marvel Studios’ “Black Panther,” the most recent movie inspired by comics that features a cast overwhelmingly not white. In fact, there are a mere two major characters that are not people of color (three if you count the obligatory Stan Lee cameo).

However, as I watched the film for the second time this weekend, I started thinking of reasons why I appreciated the film so much, or why I think the film so significant. I’ll try like hell to avoid spoiling, but no promises.

The cast was predominantly African American.

Not that my awareness of the lack of diversity in comic book films started so late, but it was an interview with Walter Dean Myers that slapped me in my white, adult face. Myers said that he didn’t see himself in the books until he read “Sonny’s Blues,” a story by James Baldwin. It was then where he finally saw his racial and cultural identity represented in literature.

“Black Panther,” I wager, will evoke similar reactions. Truthfully, you don’t even have to watch the film to get a sense of this. Just compare posters. I’ll share one, but if you can find another recent comic book movie poster that features as much as color as the one for the Wakandan monarch, I’ll be surprised.

The film is as much about strong black women, too.

Too often, the woman in a comic book film fulfils the tired “damsel in distress” trope. That isn’t to say that comic book films suffer from a lack of strong women, but this film serves us strong female characters that aren’t Wonder Woman, Black Widow, or the Scarlet Witch.

Forgive me for a second here, but I’m just thinking that two of the most badass female characters in actions films with the name “Black” in their codenames aren’t women of color. Remember Black Mamba in “Kill Bill?” She wasn’t black at all, which, either intended or not, was an in-film joke. Black Widow was portrayed by Scarlett Johansson, a woman who is also not black.

Anyways, I digress. Back to the “Black Panther” talk.

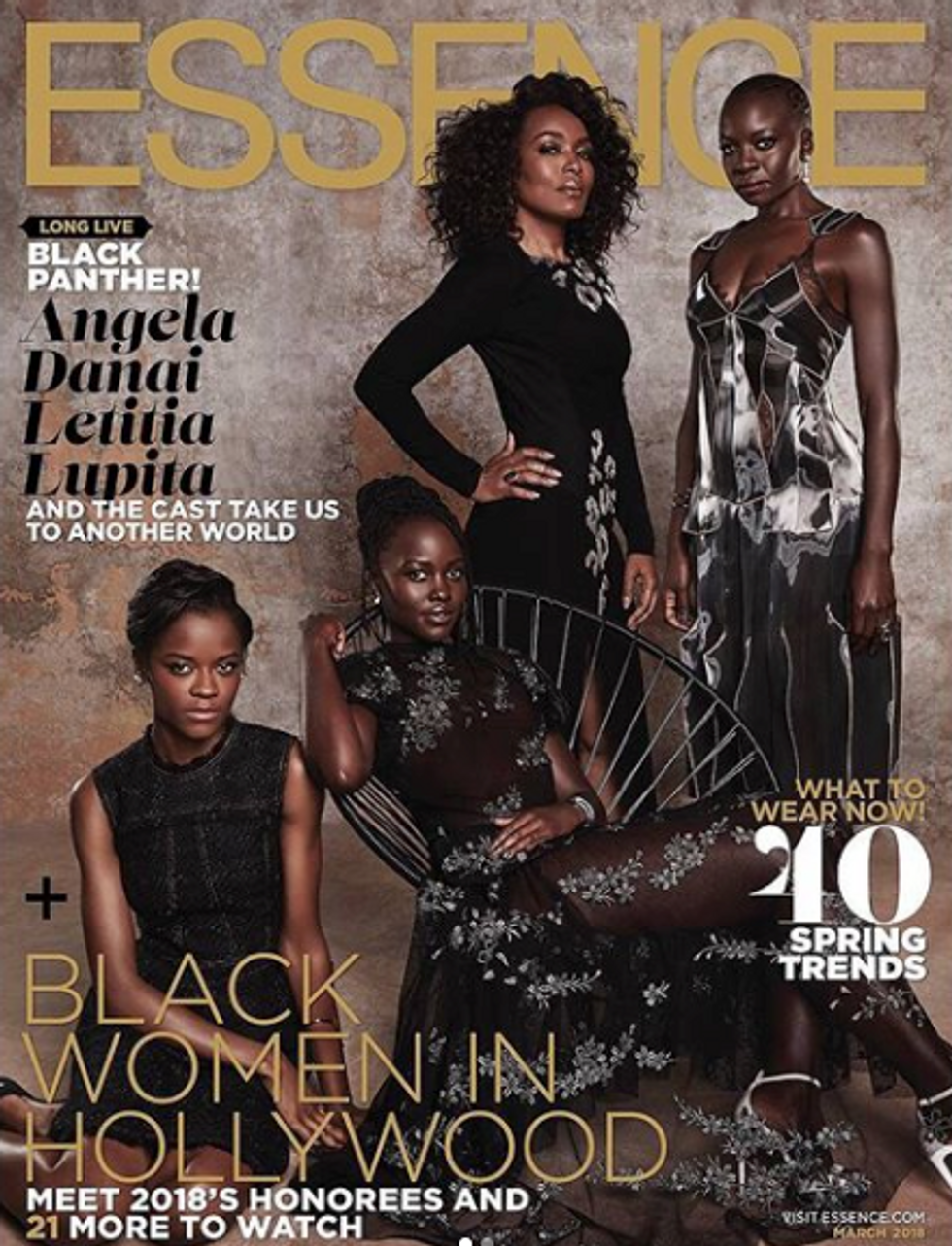

Danai Guirira portrays Okoye, a Wakandan general and elite warrior. Letitia Wright portrays Shuri, sister to the Black Panther and the brain behind all of Wakanda’s modern technological advancements. Lupita Nyong’o portrays Nakia, a love interest but still an amazingly a strong-willed and free-thinking warrior.

I’d wax even more verbose on the awesomeness of the film’s amazing African American women, but just go see the movie already.

It addresses a wide range of sensitive topics without being heavy-handed.

The film’s primary villain, Eric “Killmonger,” has an origin story that begins in an early 1990s Oakland, California, a city known for its racial tensions. Killmonger, portrayed by Michael B. Jordan, provided dialogue that a lifetime of observing oppression of African Americans. His motivations are certainly personal, but they’re also, to a small degree, noble in that they want to elevate the oppressed out of their oppression.

Despite his relatability, Killmonger represents a frequently exploited tendency to feature characters of African descent as wilder, more savage, and vengeful. Antithetical to his character is T’Challa, portrayed by Chadwick Boseman, who embraces a passive, peaceful demeanor. Conquering other nations, T'Challa stresses, is not Wakanda’s way, despite the country being capable of doing so.

Not to vilify my Eurocentric heritage, but there are instances in which white cultures were neither so wise nor benevolent. The African nation of Wakanda could have easily conquered other nations through their technological advantages, but they chose not to. In fact, the country, under T’Challa’s leadership, goes on to initiate goodwill programs intent upon helping the rest of the world.

Why is this significant to me, a white male? It’s significant because I don’t question literary or cinematic representation of my own cultural identity. It matters because I don’t have to recall decades of actors in blackface. It’s important because little effort is required to remember a comic book character representative of the same skin tone as me.

Were I a black person of any gender, I’d want to see a movie, especially a comic book movie, in which someone similar to me celebrated and not mocked. Gauging from my friends of color’s social media reviews of the film, I think “Black Panther” has done just that. I just now wonder what individuals like Walter Dean Myers might think.