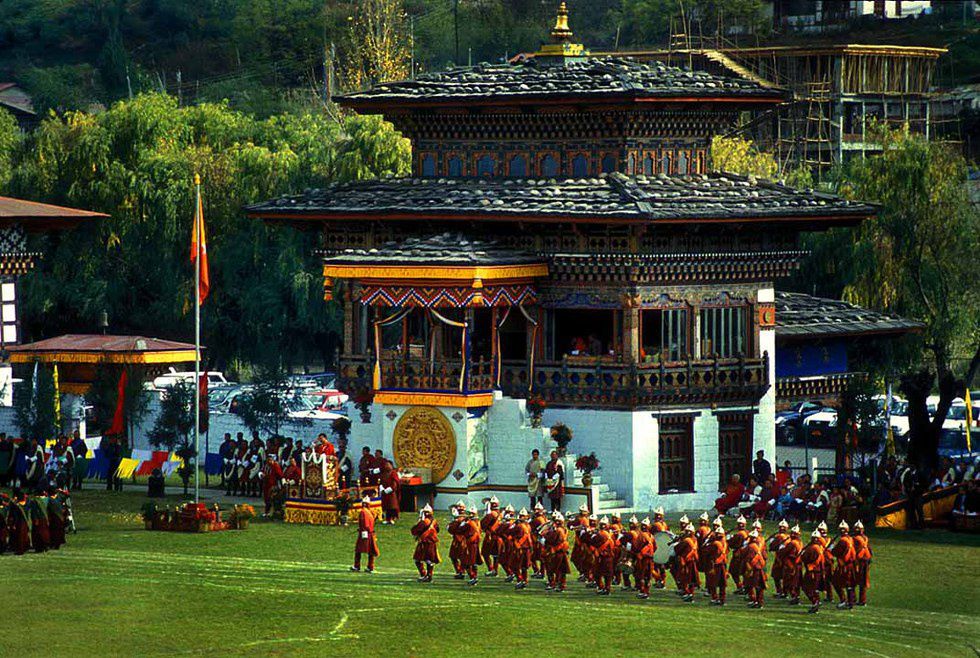

Deep in the Himalayas of South Asia, a hidden kingdom lies nestled among lush forests and expansive mountain valleys. Buddhist monks hum their rhythmic mantras as local farmers herd their sheep through pastures thick with vegetation. Exotic birds perch upon the red roofs of ancient temples, towering in the midst of a misty blue mountain sky. Surprisingly enough, this place is not the product of an overactive imagination. This is Bhutan.

Commonly referred to as “The Lost Kingdom,” the country of Bhutan has gone nearly untouched by outsiders for several centuries. It contains an astounding amount of biodiversity, lush subtropical forests, and flourishing ecosystems unseen in any other part of the world. However, its innate beauty is not its only pride. In 2006, it was rated by Business Week as the “happiest country in Asia.” How did such a small country practically untouched by the realms of globalization claim this impressive label? It all began in the 1970’s when Bhutan’s then-king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, coined the term “Gross National Happiness.”

Gross National Happiness, or GNH, is a measurement of the well-being of a nation and its citizens. It is measured in terms of the economy, environment, and culture.

Bhutan focuses primarily on this measurement, as opposed to the more commonly-used Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which is the amount of money that a nation spends, regardless of what it is spent on. In order to determine GNH, the government of Bhutan routinely sends out surveys to its citizens which evaluate the “psychological wellbeing, health, education, time use, good governance, cultural diversity and resilience, community vitality, ecological diversity and resilience, and living standards.”

These surveys are then used to formulate a GNH index, which Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Commission incorporates into all of its policymaking processes.

Why reject the norm of every other nation and completely restructure the very nature of government? For starters, Bhutan is one of the leading countries in terms of sustainability.

They have a net zero greenhouse gas emission and their largest export is hydropower harnessed from Himalayan river valleys. In addition, one-tenth of all cars in Bhutan are electric. The country also boasts a pointedly high level of biodiversity, as conservation laws reserve 72 percent of its territory for national parks. Even their children are sustainability-focused, as they attend the “Green Schools for Green Bhutan” where they learn about environmental preservation.

In addition to sustainability, Bhutan houses a population of healthy, happy citizens. The majority of its people practice Vajrayana Buddhism and their policy of Gross National Happiness is rooted in the Buddhist belief that there is more to life than simply material possessions.

They agree that the best development is social, cultural, spiritual, and environmental — all occurring in harmony, without upsetting the balance of one another. They respect and cherish the environment in which they live and believe that love and devotion to the environment will earn them good karma.

In sum, Bhutan is an undoubtedly successful country with a flourishing environment and culture. Despite the growth that it may bring to their economy, they have rejected food chains like McDonald’s and Starbucks in order to maintain their GNH and cultural identity. In a world dominated by consumerism, Bhutan has managed to thrive utilizing an entirely different socioeconomic framework. Conferences on Gross National Happiness have now occurred in Canada, Thailand, the Netherlands, and Brazil.

During a time of major environmental crises, skyrocketing mental illness rates, and corrupt governance, it is imperative that the rest of the world consider Bhutan's political framework as a possible solution for both the future of sustainability and the overall well-being of our citizens.