To many, Nepal exists in South Asia as a small, but naturally gifted developing nation, with no particular political significance in the international community. Prior to the 2015 earthquake, a very small portion of the global population knew where Nepal was located, let alone its contribution in the geopolitics of the region.

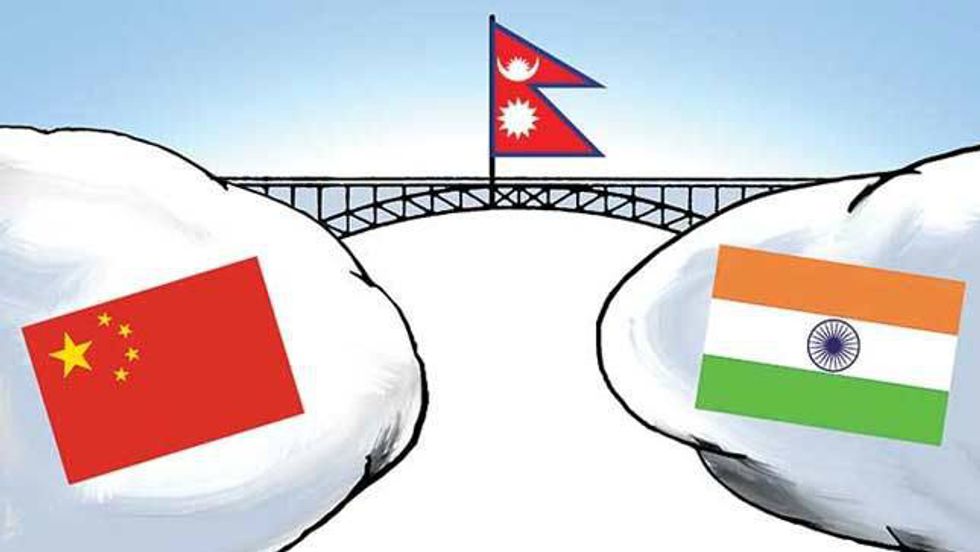

Understanding South Asian geopolitics, however, bears particular significance, as the small, landlocked country sandwiched between the two Asian giants, shares historical ties with both India and China. This results in the superpowers enjoying a marked level of political, economic and socio-cultural influence over the country. For a very long period of time, the two neighboring states have been competing for influence over Nepal, and the mountainous state has had to skillfully play each other off to preserve its sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Nepal shares about a 2,000 year-old relationship with both China and Tibet. Through marital relationships, to the exchange of sculptural artists building Buddhist statues in Tibet, the two states were closely tied to each other. The Chinese emperors, on the other hand, constantly sought to establish diplomatic relationships with Nepal, with the hope of outflanking and pacifying Tibet, which was starting to grow as a significant threat to China. Although China gained some control over the volatile Tibetan region, the unification campaign of the Gorkhalis in the 18th century presented both China and Tibet with new challenges.

While China suffered Nepal’s blockade of its trade route through Tibet to India, Tibet felt threatened by King Prithvi Narayan Shah’s expansive motives. Not surprisingly, taking advantage of the political instability in the region, the Gorkhalis attacked Tibet, to which the Qing reacted with an attack on Nepalese military in 1792. The British government avoided its involvement in the Sino-Nepalese war because of its unwillingness to risk its commercial interests with China. However, the fear of one day being confronted directly by the Chinese advance from the north made the British hope for Nepal’s victory over China. The war ended with a peace treaty that brought Nepal closer to China, “though largely on Beijing’s terms.”

Whereas Sino-Chinese relationship seemed to have improved, “Nepal’s conquest in the west had provoked disputes with the British.” When war broke out between British India and Nepal in 1814, neither China nor Tibet came to its rescue. As a result, Nepal had to cede one-third of its land to India under the Sugauli Treaty. Beijing seemed to have avoided its intervention, because the British did not pose any threat to the Tibet, “its integral part of frontier-security system.” With the rise of the Rana regime in 1846, the relationship between Nepal and British India started getting better. This dynamics resulted from China’s growing inability to influence development in the mountainous country.

The entry of external players, such as Russia, Germany and Japan, into the region further improved Nepal’s relations with the British, because doing so would preserve Nepal’s sovereignty. Similarly, the overthrow of the Tibetan government in 1910 and the subsequent instability offered the British an opportunity to influence the volatile Tibetan territory. “Although politically independent, Nepal had become an informal part of the British Empire under indirect control mechanisms such as military and trade.” Because people were getting tired of the suppressive Rana regime, and youngsters started protests against the regime in various parts of the country, the Rana rulers had been supporting the British wholeheartedly, with the hope of protecting themselves from the growing anti-Rana uprisings. In both World Wars, Nepal offered military assistance to Britain. The departure of the British from the Asian subcontinent, however, posed the Ranas a new challenge: They needed new external allies. When the anti-Rana movement reached its peak, the King, Nepali Congress and the Ranas signed a tri-patriate agreement under India’s mediation, which brought an end to the 104 years-old Rana regime.

Although King Tribhuvan had shown some inclination towards India, his son, King Mahendra, “was more assertive about Nepal’s independent place in the international community,” and sought to use China to balance Indian influence in Nepal. India and China competed against each other to gain influence over Nepal by bringing various developmental projects and offering economic aid to Nepal. King Mahendra took advantage of the competition by maintaining a balance between the two states’ influences. At the same time, its fight against global communism and Tibet’s instability caused the United States to enter the region. It trained anti-Chinese Tibetan rebels and supported them militarily and economically. When the U.S. offered assistance to its rival, Pakistan, India went on to sign a military agreement with Russia.

China enjoyed a greater influence over Nepal due to the monarch’s inclination towards the northern neighbor. Increasing democratic movements, however, led King Birendra “to cede power to the political parties, which were ideologically more compatible with India.” Although the establishment of the multi-party democratic system had brought Nepal closer to India, China enjoyed a certain degree of influence over Nepal through its closeness with the king.

Complicating the situation, the Maoists launched an armed campaign against the monarchy and parliamentary democracy in 1996. After the royal massacre of 2001, King Gyanendra came to power and sought to further strengthen Nepal’s ties with China in an attempt to counterweight India. China, too, was displeased by India’s growing contact with the United States, and thus sought to challenge it through Nepal. However, India played a stronger move by facilitating the alliance between the Maoist rebels and the Seven Party Alliance that brought an end to the monarchy.

The Nepalese democratic parties, with the alliance of the Maoists, failed to formulate a constitution and bring political stability in the country. On this account, China and India both shared a common interest in bringing stability to the “strategic doorstep buffer zone.” Although the political parties have, by now, formulated a constitution and have been ruling the country as a multiparty republic, India and China still seem to influence most of the political and economic affairs of the country.

China’s growing economy and its quest to become a regional hegemony has been balanced by the growing India-U.S. alliance. In the past couple of years, though, India has been losing its credibility among the Nepalese as a good neighbor, which China has taken advantage of. The political parties share a divided opinion about the degree of influence each superpower should have over Nepal.

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion