Making Connections in Fluidity: An interview with Los Angeles based artist Isabelle Harada

Part 1: Accidental Discovery

Senbazuru, or a thousand origami cranes, pertains to a legend far reaching into Japanese culture beginning at least 13 centuries ago with the introduction of folding paper (oru + kami) as an art form from its accidental discovery via aristocrats noticing the creases on the paper used to fold gifts.1

Cranes are seen as animals bearing fortune, they connote or bring happiness and are said to live for a thousand years. In the 12th century, it’s said that the soul of the warrior Yorimoto was transmuted into a crane when his body died and while he lived he’d leave messages on the cranes’ leg that he caught, asking anyone who’d see those cranes to write the name of the place where they were seen thereafter.1

Part 2: The Legend

Somewhere between then and now, in the amorphous procession of legend, tradition and history the custom of folding a thousand cranes before marriage to have a wish of a thousand by a thousand prosperous years of marriage emerged.

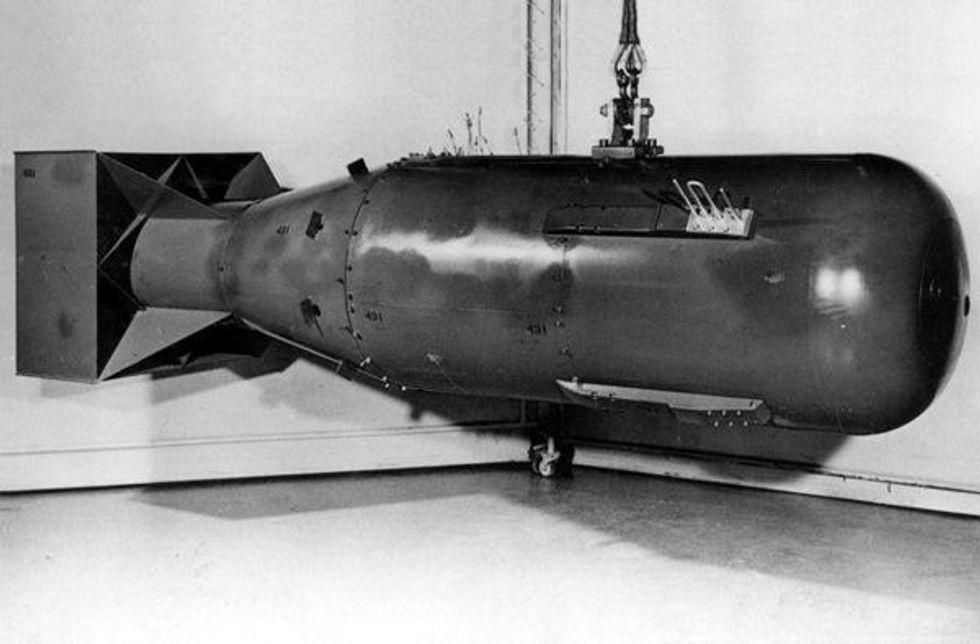

More recently, on August 6th, 1945 “Little Boy,” an atomic bomb that detonated with the energy equivalent of 15 kilotons of TNT and a larger fallout than any before left Sadako Sasaki with leukemia some months later.2

Part 3: The crisisChihuko Hamamoto, a friend of Sadako’s who’d been visiting her in the hospital since the 21st of February, 1955, inspired her to begin folding cranes. Two versions of the story diverge here.

In one, Sadako finished folding the cranes, and in another only 644 cranes, which her friends helped her finish. Either way, she died on the 25th of October and was buried with a thousand origami cranes.2

Part 4: Happenstance and the Artist (vessel which sorts input artistically)

While in Japan I began a project informed by the legend of the thousand cranes though I only wanted to work with 999. The first week back I saw that in Bergamot Station an artist was displaying 999 origami cranes at Sloan Projects titled Work/W=fd, her name: Isabelle Harada.

I went on Thursday and walked past the doorways’ draped curtains into the low-red-lit room where (I trust) 999 golden origami cranes latched on thin string spun twinkling in the straylight wattage exciting mesmerization.

I got walk around the passages between the suspended cranes alone with enough time and without the worry that someone would notice how close I got to the origami (and also to take a mandatory [for posterity] selfie) before a woman in all black tending the art (WIABTTA) walked in and sat behind the table. On my way out I went to sign a book that was open with other signatures.

DS: Is this a mailing list?

WIABTTA: Yes.

DS: Do we write things to the artist too? Like, will Isabelle see it?

WIABTTA: I’m Isabelle.

We scheduled an interview for the next day.

Enclosed below is a transcription of some of her answers. For a full transcript without all the “um,” “like” and (most) organic pauses redacted or the audio, please contact me. Exclamations generally stand in for laughter.

Part 5: The Meeting

DS:

First, a typical biography. What do you want people to know regarding your upbringing and studies?IH

: Upbringing was…pretty unconventional.My parents were never together and so as a result I’ve just always had a really morphing landscape of family members and where I’ve been living [and] located [so] I’m used to a pretty fluid lifestyle that informs my work a lot, the way that I work is often just based off of what I’m doing at that time or what happens to be around me.

I’m also working on a project where I’m building a gallery space to be viewed on a skateboard at that pace of motion...it’s just based on the fact that I like skating right now, or that I like…

DS

: Movement and time…You mention that in your thesis. The study was about relativity and how fragile the individual is…how it’s kind of [all] going downhill right?IH

: Yeah…or that things are coming together constantly like in a non-, entropic way…. The other thing about my background that is pretty relevant is that when it came down for me to be going to school it was either that I was going go to an engineering school or I was going go to art school. And it was sort of on a snap decision “I think I’m going fit in with art people better!” and I just went to art school! A lot of the things that I think about still have to do with physics and math and science and my work is based [on] that…hence, the title of my show — a basic physics equation.DS

: Right, where does that come from, this attraction to [mathematics and physics]? You were talking about a lot of heavy and dense theories and theorems in your paper.IH

: Yeah, I guess, what attracts me to it is that I see it as an empirical translation of the way that the world works on multiple levels.Relativity is a thing that not just occurs in physics but in the way that people interact and the way that the universe works. I just think it’s really interesting to be able to study these things that are in front of us and see how they interact and see what we can learn from that as a culture, on a philosophical level.

[Cigarette smoke was drawing into the vacuum of a neighboring gallery and we moved to a curb beside a tree, though not beneath it]

DS

: How does that (her childhood of morphing landscapes) inform what you’re doing? If you can describe more that ability to be in flux or knowledge that things are transitory...IH

: It gives me a huge emphasis on process usually and allows, within my work, for process to become more informative than, I think, most people.I think a lot of people set out to make a piece, come up with the idea, and then they go execute it, whereas, for me, a lot of the time the execution is, sort of part of a performance. An installation is really a lot more in depth in terms of execution, with putting it in space and so I think that during, I allow that process to change the work over time, especially in different iterations.

This piece even. I installed [it] for my mid-residency at CalArts and I did it in a big blocky chunk and there was enough room for me to kind of get in there and move around and hang things and things like that, but I didn’t make a path for people specifically.

What I found was that people were creating their own paths and [they] wanted to go in it and be a part of it and be immersed. I thought it was really interesting to watch people create their own paths and let them script their own space and see what that looked like at the end of the show. I definitely let that pathway inform the way that I decided to create a pathway for this piece.

DS

: You seem (in her thesis) to talk about the creation of art as a conscious participation in alchemy. Would you describe the process in which you’re choosing your elements? Like in your videos there seems [to be] a lot of superimposition and…overlap...involves a lot of light touching things and transparency…IH

: Yeah, when I was making more of my video work there was a formula. I’d be interesting in a physical principle, I would [have] some sort of, like Roland Barthian moment where I would really, in my gut, feel that physical phenomenon in something that happened to me socially, and then I would, within that equation [establish] who am I, who is this person, what were they doing to me. What is that action? Are they multiplying, are they dividing? Then I would parse people out into a variable. They would become x and I would become y and then I would build my narrative that way and let that process of writing a mathematical proof become the trickle down narrative.DS

: Right. (not a “oh yeah, duh” right but a “whoa” right)IH

: What alarmed me at first, but then what I found really I enjoyed was that…I was always wrong.DS

: In the piece?IH

: Yeah, in the piece, in the work itself, and so, after seeing those things…those are the moments that I decided were the crux the work, those were the things to start exploiting. So then I started moving into installations that create moments to explore like that, where I don’t know. Where I haven’t determined whether or not, who is working in that piece really. Like, you know…is virtual work more than the…I didn’t actually say…I don’t want to take a stance.DS

: So, it’s just the next theorem that you devised. Having something concrete like a video just doesn’t seem to be as dynamic as the life you’re trying to reflect.IH

: Yeah. My medium lineage started in photo, went to animation, which [is] “oh, photos in time!” and then really thinking about how they’re working in time. Then it was “okay, animated installation, now I’m working with people within time within space” and then here I am. I just keep adding more physical elements.DS

: There seems to be an underlying knowledge or sensitivity to determinism in your pieces where nature is overriding. Like, whatever nature does, or whatever the bigger law is, that’s kind of what we’re damned to follow. At the same time you’re creating something so you’re moving away from [that] apathy, which a lot people feel. What would you say to people that feel apathetic when they feel determinism looming in everything?IH

: You know, it’s difficult for me to answer that because I don’t know how to change that. For me, what helps is working through it, you know: folding a crane or turning it into something…trying to turn it into something productive to think about.When I feel like life is somewhat out of my control and I go down certain thought paths...like, when you’re meditating it’s good to follow a path, but certain times, you know that that path doesn’t actually go anywhere productive and you end up tumbling in this weird way. So what I try to do is tell myself when it’s time to cut that off and/or flip that. If I can’t flip the switch off, then flip it to be something new.

It’s really difficult and sometimes it takes a couple months to be able to do that with an idea for me. My entire process and practice is doing that…making lemonade and that’s it.

DS

: So there’s like a process of self-control and self-observation [there]…IH

: Yeah, and remembering that, you know, you are a tiny little baby speck in this entire universe and…this is so cheesy, but really remembering to appreciate all the good things and actually vocalizing them and actualizing your thoughts about [it]…the materiality of the actualization, something you can actually grasp.I said “I’m so thankfully that I have this show happening right now,” I have to remember that every day.

DS

: You describe yourself as a “post-internet artist.” Can you describe what that means to you?IH

: To me…knowing that the internet exists. It’s no longer “WOW! THE INTERNET IS PROVIDING US WITH GLOBALISM!” For me, post-internet is, “okay, the internet is providing us with globalism buuuut *sustains a shrug* only if you’re in a first or…maybe a second world? but not really a third world.” Globalism is way for capitalism to continue to hold its power and in a way…DS

: Imperialize...IH

: Yeah, and to let us believe that we are actually seeing the way that the entire world looks. When really, we’re not.DS

: So it’s like getting over it kind of?IH: Yeah, I see myself as an artist whose sort of over it.

And as somebody who, you know, grew up in the age when it was still [not something to be over]. I have gone through the phase of being wowed by it and then realizing that I made some faustian bargains with it. Like when you google me and my Myspace page comes up and I don’t even remember the password to [it] anymore and I’m just like “Awwww man! that’s like 14 year old me...on the first page of google, representing me, even though I’m doing all this other stuff, ay wow, I gotta get on my meta-data game,” you know?

For me, now, it’s just being conscious of like, who I am as an individual and realizing that, as Donna Heraway says in The Cyborg Manifesto “technology is an extension of us.” It is my identity and just as much part of me as my hand is at this point. I have to hold myself accountable to that.

DS

: It becomes this kind of, moral barometer doesn’t it?IH

: Yeah.DS

: I also want to talk about space. Bergamot Station is a really cool place. What do you think about the aesthetics of the space and what do you plan to do with it in your next project?IH

: The space is a little bit pre-determined…I don’t really know how to describe the process. Space is much more intuitive to me because a lot of the time I don’t really even know what it’s going to be like until the very last minute. Even within the space there [gestures towards Sloan Projects where W=f/d is being exhibited] a month in advance, I was like, “Okay, this is what I’m going to do, I’m going to wrap wood in fabric, I’m going to pull it across the way, and it’s going to be taut underneath the lights, and I’m going to be able to shove lights underneath and hold the fabric up, it’ll be fine…”DS

: Uh huh...IH

: I get in there, and of course, the fabric is drooping, and it’s got this new lovely shape that I like a lot, but “No, I’m not going to be able to shove lights in that way” and, “it would change all the way that the cranes had been hung already, so I’m not going to do that."With my work I have an idea of how it needs to be, the minimal requirements of what it needs to do conceptually, within that I work to affect the space as minimally as possible actually. I find it to be distracting if you do too much, then the message is muddy.

DS

: So it’s intuitive… once you’re there you interact.IH

: Yeah. I will say that working at Bergamot every day is, in terms my own practice, really interesting and inspiring to just [be able to] see the way that people look at art…It does inform the way that I think about people moving within the space but only a sort of gloss[il]y, like in a “being processed way.”DS

: Okay. College students are going to read this so, for the artists that are working, especially [in] visual, but also any kind of medium...actually, what would you want to say to your younger self and them?IH

: That your work is incredibly important…but you can’t put it on a pedestal.I would say that you need to actually just stop fucking around and sit down and make something and stop sitting and thinking about what you’re going to make.

Get down and do it. Even if you don’t know what you’re doing just make it part of your practice to work every single day, because if you don’t do that it’s so easy to fall off and fall out.

I would also say that part of your job as an artist is to be a social being and to, not just because you’re taking the temperature of culture to get it so you can spit it back out to culture, because that’s fine, just…if you want to be a gallerist you have to talk to people and you have to know people.

That’s the way the art world works, you get curated by your friends and you get opportunities by meeting people and knowing people, just don’t go about it in a schmoozy way.

You don’t just get things from people, you make things with people (inaudible because of wind though she laughed.)

I found that to be very true in the last couple of months. All of my collaborators are people that I really respect, enjoy the work of, and enjoy talking to.

DS

: Cool. Okay, a final question. The legend of the thousand cranes stipulates that you should fold a thousand cranes, why did you leave one crane unfolded?IH

: I wanted to think about the potential. I wanted to demonstrate that there’s something beautiful in incompletion. I wanted to demonstrate that…despite the fact that I didn’t make it [all]…process is beautiful.I was engaged, and then, I wasn’t but I had started folding the thousand cranes for Japanese engagement and uh, one day, couple months into it….incident…break up. I found this box and, I was feeling kind of bummed and I was [thinking] “That’s so strange that I put in all this effort and you know, what does that mean?” and I wanted to explore that a little bit more.

Folding was cathartic, and [then] “I wonder if I fold a thousand of them and I just wished to not feel shitty anymore”, or something like that…that was like “oh hohohooo” and then I started folding one and then I thought, “Wait no, there’s actually more meaning in this, and it would be way better to fold many.”

DS

IH

: Yeah, there’s no way to know how something is going to change while you’re making it. For me there’s no point. At the end of my thesis what I discovered was that you could’ve applied all these [values] to specific cases [variables] and they would work, and then in some cases they [wouldn’t] work because, some things in life are not that way. There are some physical anomalies and things are never perfect. You can strategize all you want but you really have to just get down in it and just do it, be a part of the process, be a part of all these things otherwise what are you doing?Why do we try to structure and find categories for things that, in the end really just defy them naturally...

DS

: Thank you for your time.IH: Yeah.

Part 6: A choice I leave to you

Work/ W=Fd by Isabelle Harada is on display at Sloan Projects in Bergamot Station until the 30th of July.

Isabelle's resilience to create and manifest affirms her intuitive interaction with the alterable world and an innate acuity to her fluid proprium; that interdisciplinary approach to art marrying physics and philosophy helps inform us of the cognitive gymnastics vital to sustaining a sense of peace in whatever pursuit we dedicate ourselves to.

Check out her website here.

Works cited:

1. http://traditionscustoms.com/lifestyle/senbazuru

2. http://www.hiroshima-is.ac.jp/?page=sadako-story

Photos used:

- origami cranes - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One_thousand_origami...

- little boy - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Boy

- sadako sasaki - http://i.imgur.com/4WItXlO.jpg

- Part of 999 Cranes – Diogo Segovia

- Isabelle before the Cranes – Diogo Segovia

- Suspended Cranes (cover photo) - Diogo Segovia