Bats, jumpsuits, pretty ladies, billionaire lifestyle, fast cars, big weapons, and a good ole bowl of justice in the morning. It’s hard to not want to be the comic and movie sensation - superhero Batman. It’s also hard not to want to be his separate identity billionaire Bruce Wayne. Combined it sounds like a dream come true, right? No worries, no cares. Just fun superhero gadgets. Except… wait. There is that whole thing about what to do with the bad guys, right? To kill or not to kill, that is the question.

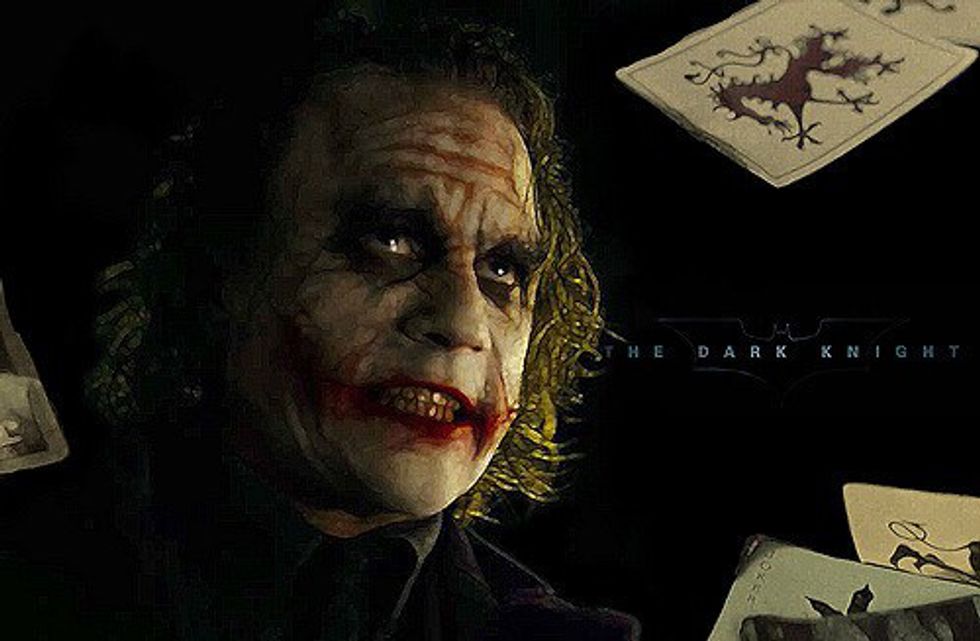

In both the comics and the movies, for Batman, his greatest battle with this ethical issue is found in his enemy the “Joker” - a psychopath dressed as a clown, usually enclosed in Arkham Asylum who routinely breaks out to cause mayhem in the city, killing many lives in the process. When discussing the issue, we look no further than Mark White’s article, “Why Doesn’t Batman Kill The Joker?” found in the book “Batman and Philosophy.” While some may argue it isn’t right for him to kill the Joker, this leads me to explore the idea that Batman should break his rule of never killing anyone to kill the Joker and save the lives of hundreds of innocent people. To help dig deeper into this thesis, we will go through the depths of Batman’s superhero lifestyle, his previous attempts to deal with the Joker, and tie it all back to the philosophy theory of utilitarian values.

So, to discuss this moral and ethical issue of “murder” and “justice," let’s look at what kind of hero we hold Batman to be. In the comics, Batman has many opportunities to kill the Joker, saving the lives of many people. However, that would go against his personal code of honor to never kill. But even when someone else has the chance to kill the Joker, Batman still stops them. The opposing idea here is that if Batman killed, or allowed the killing of the Joker, “it would make him as bad as the criminals he is sworn to fight” (White, pg. 6). If Batman allows his justice to fall to the moral status of a criminal, than he himself would become a criminal. Batman finally comes to a point where he was almost pushed far enough to kill the Joker and says the line, “How many more lives are we going to let him ruin?” to which, Detective Gordon, a close friend of Batman, says, “I don’t care. I won’t let him ruin yours.” This implies that Batman’s integrity and own morality is more important than the risk of killing an evil man and saving lives. However, to support my thesis, let’s take a look at what kind of hero Batman is in the first place to decided if his morals really should be held at such a high esteem.

In the second movie of the recent Batman Tiology, “The Dark Knight”, Gordon says:

“…he's the hero Gotham deserves, but not the one it needs right now. So we'll hunt him. Because he can take it. Because he's not our hero. He's a silent guardian. A watchful protector. A Dark Knight.”

I bring this quote into light because it specifically says that Batman isn’t a hero. He cares for the city, and will become a vigilante and hold a bad reputation for the sake of others, but he doesn’t follow rules, he doesn’t have a superpower, only a lot of money that gives him the opportunity to fight crime, which yes, is an endeavor that is honorable and good, but also can go to one man’s head.

As the counter-argument would say: his justice is worth more than the flaws he has. As I see it, I’m not saying that he should stop ending crime, or that he isn’t doing well at what he does, I’m saying that it’s unfair for him to claim to be a hero, but then draw the line at ending a man who has killed, and will always kill, numerous people.

For example, when we take away the mask, Batman is nothing but a billionaire playing dress up in fancy gear and gadgets, thinking he is above the law to protect a city that in many ways resents his true identity as Bruce Wayne. Does a rich playboy with the money to become a hero really make him one? What was the deciding factor that his morals were better than the law’s to decide the fate for other people.

Let’s look at the “trolley problem” to decide this. Due to the work of Phillippa Foot and Judith Thomson, the idea of ethics in regards to responsibility to others comes into play. For example:

“Imagine a trolley car is going down a track. Further down the track are five people who do not hear the trolley and who will not be able to get out of the way. There isn’t enough time to stop the trolley before it hits and kills them. The only way to avoid killing these five people is to switch the trolley to another track. But, there is one person standing on that track, too close for the trolley to stop before killing him. Now imagine that there is a bystander standing by the track switch who must make a choice to do nothing or divert the trolley to the other track, saving the five people, but killing one” (White, pg. 9).

Now, let’s say the bystander is Bruce Wayne, the five people are little toddlers, and the one person on the track is the Joker, a man who has killed many innocent people and will continue to kill. The question is, does the bystander (in this case Bruce Wayne) have a moral obligation to divert the trolley to the second track? Is it just an option, or is it a responsibility?

Now, there are two views that come into play here. The opposing view to my thesis would say that no life is in the hands of one man, and thus Bruce shouldn’t have to make the conscious decision to kill anyone for intrinsic reasons. Then, of course, there is my view, which is that he should switch the track to save the greater number of people, and erasing a person who has, and will, do greater damage. This ties into the utilitarian view later on in this article.

A compromise to the idea of killing or not killing the Joker for justice leads me into my second point, which is leaving the Joker and finding other ways to prevent and stop him never work. Batman continuously “catches Joker and puts him into the ‘revolving door’ of Arkham Asylum” (White, pg. 6). Each time, Batman knows that the Joker will escape, and will almost without fail kill again, but Batman does his best to stop him each time, which occasionally he can’t do, costing lives of innocent people due to his lack of ability to simply kill the Joker.

And let’s discuss the Joker character. I would understand the dilemma if there were redeemable qualities in the criminal. If he showed remorse or guilt or the ability to change; but we never see these traits in the Joker in the comics or movies unless it is a ruse, which by now Batman knows it always is. He doesn’t have a family relying on him nor a normal productive life. He only lives to kill and go in and out of the asylum to play with Batman. So, when applying this to the real world, I can see how this issue becomes a bit more difficult, as we like to hold out to give people their best chance to be good and save lives, however in this fictional world, there are very few reasons why Batman doesn’t kill the Joker other than his own selfish desires.

My point here with what I’ve said above is that I’m all for redemption and second chances, but as you’ll see throughout the movies and comics, the Joker doesn’t change, doesn’t relent, and the more times Batman uses the excuse of trying to be a good guy, he is inherently being the bad guy by letting the Joker repeat his murderous ways. As Gregory Maguire said in “Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West”, “People who claim that they're evil are usually no worse than the rest of us... It's people who claim that they're good, or any way better than the rest of us, that you have to be wary of.” People who support Batman in saying that he shouldn’t kill the Joker because it makes him more like the criminal he’s trying to stop are obviously missing the point where by letting the Joker live, when all other options to stop the evil mastermind besides killing him have failed, means that Batman, the only man who can successfully kill the Joker, is just as guilty and “evil” as the Joker for the deaths of all those people.

This last point, along with the first one, both have underlying themes and ideals into the philosophy theory of utilitarianism. What is utilitarianism, you may ask? Well, referring back to White once more, it is “a system of ethics that requires us to maximize the total happiness or well-being resulting from our actions to the greater number for the greater good” (White, pg. 7). The perfect example of this is the earlier trolley example. The point is, Bruce Wayne, as simply a rich man, does not hold his own morality over the lives of others. Let’s compare this to the deontologist view, the one that I think Batman is obviously following currently. Deontology is to “judge morality of an act based of features intrinsic to the act itself, regardless of the consequences stemming from the act” (White, pg. 8). The basic point here is that the end never justify the means versus utilitarianism where the ends always justify the means. This means that deontology believes in agent-specific rules: a.k.a. when saying “Do not kill,” they mean “You do not kill," because it’s an intrinsic ethic of your own, meaning that the rest of the world can burn down, but at least you didn’t break your own rule, so good for you (White, 9). What I’m suggesting is a more agent-neutral rule, which is basically summed up as “maximize well-being” (White, pg. 9).

Why am I making such a big fuss over this, you may ask? Well, my point is, if Batman considers himself a superhero, then he must want to help people. To help his job, he would probably like to help the most people as he can efficiently. This means that if we are to truly accept Batman as a superhero, and he truly does what he does for other people, and not just to entertain himself, then there is no excuse not to kill the Joker, a criminal who has proved he is beyond salvation and cannot be stopped any other way and serves a real threat to all.

In conclusion, after looking at all the fun things Batman gets to do, I can see how many would like to be him. However, when faced with the ethics of killing a villain, I would never want to be in his shoes to make the moral decision. Seeing as Batman is a hero, putting him in the position to save the greatest number of people, then I think Batman has the responsibility to kill the Joker. After looking at the type of hero Batman is, the Joker’s pattern as a villain, and different philosophical views of the issue, I hope you agree with me too.

Author’s Note: On a personal note, I totally love Batman, he’s one of my favorites, so understand I was expressing a view to support my thesis, not bagging on him.

Works Cited (MLA):

White, Mark D., and Robert Arp. Batman and Philosophy: The Dark Knight of the Soul. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2008. Print.

Gregory Maguire, Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion