In late 2019, two Asian giant hornets (Vespa mandarinia) were found in Blaine, Washington. Currently, there is no confirmation as to how they entered the United States, but it is speculated that they may have arrived via international cargo from one of their native countries. As the media has so spectacularly conveyed via their colorful moniker, "murder hornet", there are potential health risks associated with their presence. In Japan, for example, fatalities associated with Asian giant hornets are estimated to range from 30 - 50 people per year, with most dying of anaphylactic shock, cardiac arrest, or organ failure. Although these potential health implications should not be taken lightly, it is important to address the likelihood that someone in the United States would even encounter an insect of this species.

First and foremost, the two Asian giant hornets found in Washington were dead, and although several entrapment efforts are currently underway, there is no certainty that they have become an established population within the United States. In addition, assuming they were to become a more prominent species, it would take an incredulously large amount of stings to induce life-threatening health problems within individuals lacking allergic reactions to envenomation. In fact, a case study published in 2009 concerning Asian giant hornet victims in Japan revealed that those who died from Asian giant hornet encounters had received an average of 59 stings, which is significantly greater than in those who survived, having received an average of 28 stings.

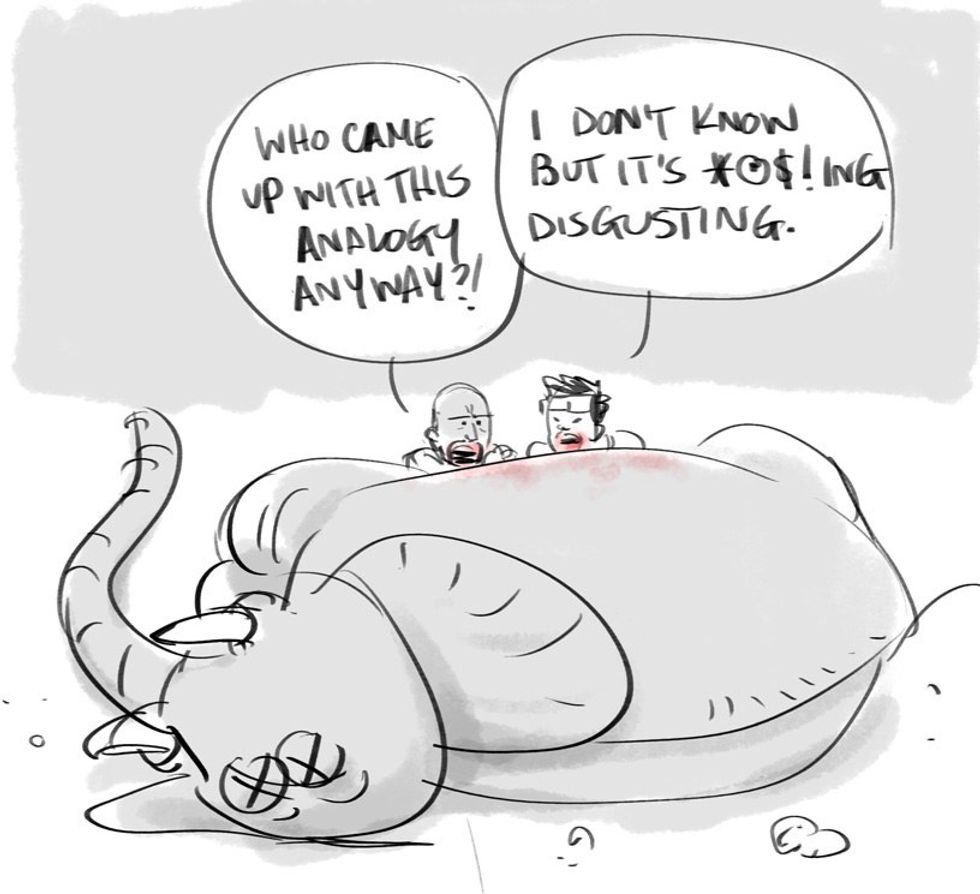

If this doesn't ease your nerves, perhaps it's comforting to know that entomologists appear to be more concerned by their potentially detrimental ecosystem impact than by their interactions with humans. Honeybees, for example, are one of their favorite prey. Upon the discovery of a honeybee population, Asian giant hornets initiate what is referred to as the "slaughter phase" of their attack where, in a matter of hours, they can decimate an entire bee population via decapitation with their large mandibles. Subsequently, they occupy the nest for a week or longer, feeding themselves and their young with honeybee pupae or larvae.

Interestingly, Japanese honeybees (Apis cerana japonica) possess a unique defense mechanism against an Asian giant hornet invasion. If a hornet were to enter their nest, for example, they would swarm around it, forming a structure referred to as a "bee ball" in which the temperature can reach over 115 °F. Essentially, they cook and suffocate the hornets with CO2 until they die.

European honeybees (Apis mellifera), the most widespread commercial pollinators, however, have no effective defense mechanism against these hornets, leaving them completely vulnerable to an Asian giant hornet attack. Naturally, European honeybee decline within the United States could negatively impact pollination, plant species subsistance, and ultimately food supplies, but again this hornet species appears far from established enough to incur such large-scale ecosystem repercussions.

Overall, it may be tempting to succumb to the mass hysteria surrounding Asian giant hornets, as their potential impact on individual human and ecosystem health are real, but the lack of certainty concerning their population establishment within the United States and preemptive entrapment measures currently underway significantly lessen the likelihood of these fears becoming a reality. There are much more pressing matters to attend to at the moment.

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by

Photo by

Photo by