"...December 7, 1941, a date which will live in infamy..." On December 8, 1941, the day after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, the United States's most important naval base, President Roosevelt declared war on Japan, entering the Second World War. As had happened with German Americans after the United States finally entered World War I, Americans grew suspicious of Japanese Americans, and by extension, all Americans of Asian ancestry. It is the author's intent to review the what effects the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and America's subsequent entrance in World War II had on Asian Americans during this period, analyzing their treatment at the hands of the American government and the public, as well as the how the Asian Americans responded to this treatment.

This is a two-part study: Part I will cover the initial stages of the American response to Pearl Harbor, Part II will cover the effects of this response on the Asian Americans who were interned.

American Government's Response to Pearl Harbor

When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, they also attacked America's other West Coast islands, most notably the Philippines. Catching America completely off guard, the Japanese swept the islands. The quick takeover struck fear into the hearts of the American people and the government, as the military buildup at Pearl Harbor was meant to deter Japanese activity in the American-controlled regions of the Pacific. Instead, the Japanese had not only taken these regions, they had neutralized the United States's base of operations.

The American government then began to worry about which side Americans of Japanese descent would take in the war against Japan. Most Japanese Americans at the time lived in the West, which was near the regions the Japanese had originally invaded. Fearing an all out Japanese invasion of the United States, the government suspected that Japanese Americans would aid the enemy effort by espionage and sabotage on the West Coast, and without cause the FBI strategically arrested 1,291 of these citizens' community leaders within hours of the Pearl Harbor attack.

Matters were not helped when it was discovered that one of the few Japanese pilots to be shot down at Pearl Harbor, Shigenori Nishikaichi, crash landed his aircraft in the Ni'ihau island in American-held Hawaii, where he received the aid of three Japanese Hawaiians. Although he was captured on the 13th of December, six days after Pearl Harbor, this incident escalated tensions between white Americans and Asian Americans, with many whites confusing Filipino and Chinese minorities with the Japanese population, making many whites hostile to anyone of Asian descent.

In 1942, the U.S. Army sent a representative to Congress, General John DeWitt, to the federal government to argue for the relocation and internment of Japanese Americans. At the time, General DeWitt commanded the Pacific division of the Army's IX Corps, and as such he was a strong proponent of internment camps. Stating that he was against the Japanese American presence in the west, he said that "American citizenship does not necessarily determine loyalty..." and that "we must worry about the Japanese until he is wiped off the map." Citing reports of espionage that included the destruction of power lines in the West after Pearl Harbor (which itself was later discovered to have been caused by cows), DeWitt convinced the government to take action. On February 2, President Franklin Roosevelt issued an executive order allowing the Army to relocate Japanese Americans from Washington State, Oregon, and California to Midwestern states, who in many cases opposed WRA camps because they did not want Japanese American presence in their regions. On February 19, he issued the now infamous "Executive Order 9066" which granted the Secretary of War the power to create military zones in which to inter the Japanese American detainees. Similarly, the March 18 Executive Order 9102 formed the War Relocation Authority (WRA), which spearheaded internment. This organization was responsible for the arrest of over 117,000 Japanese Americans along the West Coast, where the total number of these citizens equaled 125,000.

The camps created were devised so that the prisoners could sustain themselves. The federal government provided food, housing, and medical care, which it paid the interns themselves to administer. Anywhere from 7,000-18,000 were held in a single camp, granted small farmland and "city jobs" paying up to $19.00 an hour. "Housing" however, was more like a military barracks: single room shelters with cots provided the warmth of one coal-fueled stove per shelter. The camps were surrounded by barbed wire fences guarded by American troops who shot anyone that came too close to the perimeter. The prisoners were not generally treated harshly, but occasionally there were riots or attempted escapes within the camps, and the interns were not often properly supplied with provisions.

Response of the Public to Internment

The American public's response to the government's internment is often depicted as supportive, but in truth, the people were divided. When the WRA officially began rounding up Japanese Americans on March 24, it operated under a policy which stated that any American with so much as 1/16 of Japanese ancestry would be sent to the camps. This meant that sometimes even Americans of other races were also arrested, something the public did not respond well to.

This does not mean that all white Americans were against it. Racism against Asians was nothing new; Americans had discriminated against them ever since 1864 when the Central Pacific Railroad brought in laborers from China to aid in building the western Transcontinental Railroad. Treatment of Asian Americans had been roughly the same as the treatment of black Americans after the Civil War. States had impossible regulations that marginalized their societal and economic status, and city councils banned Asians from entering their cities. Like blacks, it was much easier for an Asian to prosper in an all-Asian American community than it was for them to thrive in white society. Thus, many whites were more than happy to agree with the federal government.

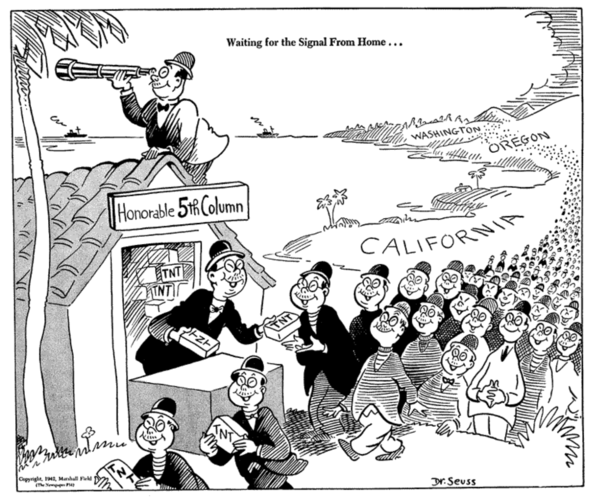

American media was less divided. Most mainstream media sources supported the government, including the L.A. Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, and the New York Times. Literary figure Ted Geisel, the famed Dr. Seuss, was a staunch supporter of Japanese American internment, even drawing propaganda cartoons like the one below:

Interestingly, most of the newspapers cited had opposed internment of Japanese Americans prior to Executive Order 9066. When President Roosevelt issued the order, and when the Congress passed legislation to back him up, these newspapers supported the relocation program. One of the only consistent media sources was famous American photographer Dorothea Lange, whose photographs throughout World War II depicted the reality of life for Japanese Americans after relocation began. The government suppressed her photos until after the war, beginning to allow their publication after the Japanese surrendered in 1945. Most other media opposition was not mainstream, rather, a handful of small town newspapers whose reach did not extend past their towns were the primary source of opposition to internment.

Conclusion

The American government and the public were motivated by intense paranoia to imprison their fellow citizens. Without provocation, the government arrested the Japanese Americans, seizing their property and taking away their livelihoods in the process. Even had some Japanese Americans in the mainland United States attempted to sabotage the American war effort, there would be no justification for en masse arrest and relocation. American citizens of any ethnicity should be protected, and although the Japanese assault on Pearl Harbor struck fear in the hearts of the American authorities and the people, this should not have turned them against their fellow citizens of Japanese descent.

- Pre-War Discrimination > World War II & Roundup | Exploring JAI ›

- Asian Pacific Americans in the U.S. Army | The United States Army ›

- Asian Americans in the U.S. Military ›

- Asian American History – Japanese American Citizens League ›

- Asian Americans: World War II - Calisphere ›

- Military history of Asian Americans - Wikipedia ›

- Essay 10: Asian Americans and World War II (U.S. National Park ... ›