My “Art of the Andes” course last semester focused on one question: What is art? We read numerous scholarly articles and compared the artistic value of everything from the Cotton Pre-Ceramic Chinchorro mummies to the Early Colonial Wooden Qero. It was not until studying for the final and recalling everything I had learned in the class that I realized I still did not have a conclusive answer to the question. I found myself asking the same question when I was reading about the art dealer who sold fake art supposedly from famous artists to the Gaston & Sheehan auction house in Texas. Over 15 years she sold fakes that she claimed were created by artists such as Rothko and Pollock.

What shocks me the most is that people trained to know famous art and its value were unable to recognize the works as fraudulent. It makes me question whether people regarded the works as art because of their supposed creator, or if the works are recognized for their value in the art world. The mishap, which occurred in 2013, is relevant again because Rosales’ own works are now up for auction; however, the works are not identified as her works. This suggests that the auctioneers think the art can stand alone without the creator’s status, or notoriety in Rosales’ case, increasing its value. This is different from the other pieces that she copied, which relied on the famous signature to make them have so much monetary value. Are the counterfeit pieces considered art if they have false origins. Maybe their artistic value lies in the fact that Rosales could replicate it to the fact that everyone believed her, thus provoking us to discredit the claim that “seeing is believing.”

The counterfeit works came with paperwork, so no one had a reason to question their authenticity. The appraisers simply put a monetary value to it. Does this mean that the works’ values come from the artist or the aesthetics and process of the work? It makes us wonder who ultimately decides which artists become famous, whether it’s because of their innovation or their craftsmanship. How can Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling possibly be compared with Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold? The former took four years to paint while the latter could have been completed in one sitting. Time and effort do not define art, but what does?

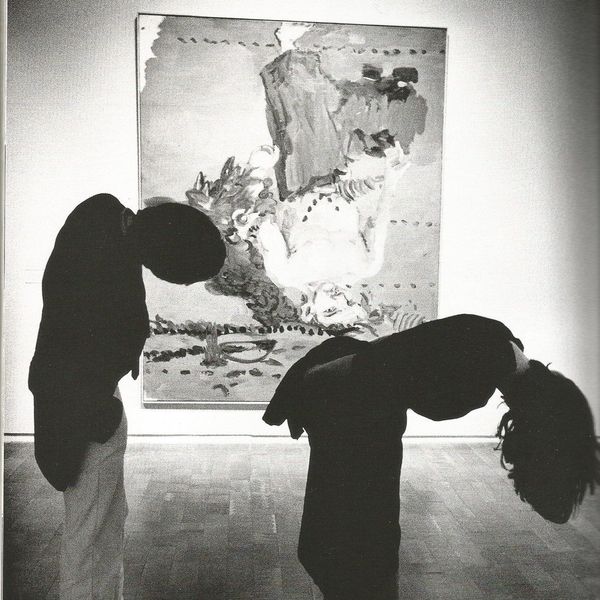

So, what is art? Where does it get its value? Will we ever have an answer to that question, or will it forever be a topic we avoid answering completely? When I see a Rothko work in a museum I think about how I could have done that with my eyes closed, but why is he famous? It might be because someone important decided his art held value, or because of the historical context of his works, or because of his thought process behind the piece. Regardless of the reason, there is something that connects the Venus of Willendorf to Duchamp’s Fountain, but until we have a clear notion of what they have in common, we just have to accept that they are two examples of art.