There are only so many discoveries left to be made, and archaeologists aren't having any mercy on future generations.

If you take a look at recent archaeological discoveries, you'll see that some of them date back as early as World War II, the Cold War, and Vietnam. We millennials might not realize it, but that's really recent. Compared to when we were discovering the pyramids and ancient Greek texts millions of years ago, this is history that's happened during some living people's lives! If this keeps up, then soon enough there won't be anything left to discover.

Today's archaeologists are Hellbent on making discoveries at any cost, leaving nothing for future generations. It makes sense: if you've ever played in a sandbox and pretended to unearth ancient artifacts and dinosaur bones, you'd know why people want to keep discovering and discovering. But now, imagine that you and the other kids dug up all the dinosaur bones, took them away, and then another group of kids came by the sandbox and found nothing but, you guessed it: sand. Pretty terrible, right?

This is precisely what's happening in the archaeology field. All of the old archaeologists from the WWII era are digging up dinosaur bones and Egyptian artifacts around the globe and nobody's there to hold them back. These researchers have no forethought for how their descendants will feel when they begin playing in an empty sandbox.

This is why I,

World Renowned Archaeologist Eto Kowalski,

have come up with a solution.

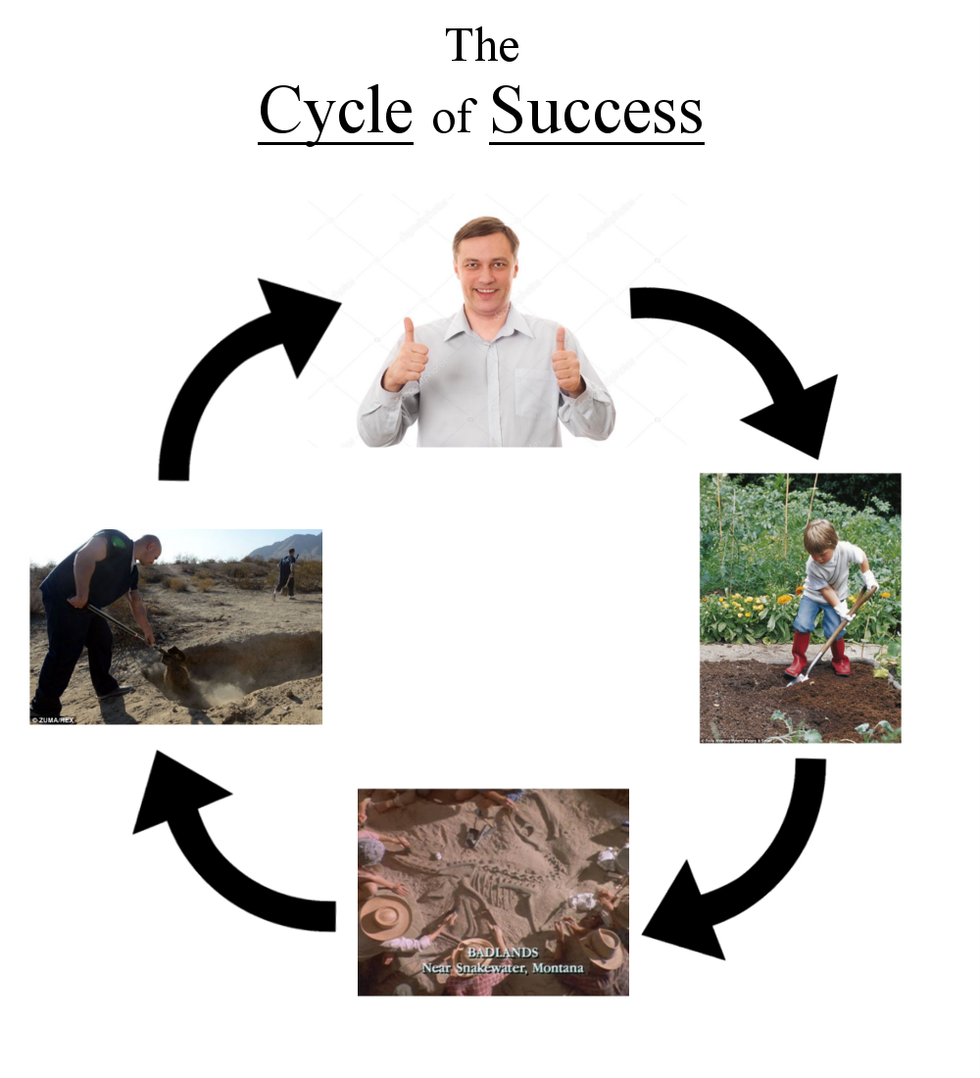

In order to combat the menace that is over-zealous, glorified gravediggers, I propose that we begin planting new discoveries to be found by future generations. To go along with the sandbox metaphor: after we excavate the dinosaur bones, we re-bury them before leaving to go play somewhere else. Let's be real: who really needs those bones? It wouldn't do any harm to let future archaeologists have some fun, too. We'd dig up brand new bones and artifacts, take a cute selfie, and re-bury them. No one would be the wiser.

This creates an ever-lasting cycle of archaeology and immediately solves the problem of dwindling discoveries left on Earth. Genius? Perhaps. Necessary? Absolutely.

I understand that not everybody is linguistically inclined, so if you're confused and have an IQ lower than 300, try following this simple 4-step process that I've personally illustrated by hand.

Fellow scientists, fellow archaeologists: let's make amends before it's too late-- this is the least that we can do. I know I, personally, will be spending my next few weeks re-burying fossils from the MFA, and I hope you can all join me in helping future archaeologists find a little more meaning to their work.