As the Russian Air Force continues airstrikes in Syria with the intention of combating ISIS, a new wave of public attention has fallen on Russian President Vladimir Putin. Putin's claim made in a widely covered speech to the UN that his intervention is "not about Russia's ambitions... but about the recognition of the fact that we can no longer tolerate the current state of affairs in the world" has been received with skepticism in the West, where he's accused of attempting to prop up the Syrian government and resurrect the type of international influence once held by the Soviet Union. The reason for Putin's interventions in crises in places like Syria and Ukraine isn't the consequence of a power play by Russia, however: it's the result of desperation.

While Putin called for an international coalition to fight against ISIS "Similar to the anti-Hitler coalition" of WWII, it is common for Westerners to call Putin himself a modern analog to Hitler. Conservative Historian Paul Johnson alleges that Russia is being allowed to pursue his goal of "revers[ing]... the end of the Soviet state and dissolution of its enormous empire" while Western powers sit on their hands like the modern day versions of UK Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, attempting to use appeasement instead of military force. Even Hillary Clinton claimed last year that Putin's vocal desire to intervene on behalf of people with Russian origins in foreign nations is similar to "what Hitler did back in the 30's."

These arguments all operate on the assumption that Putin's motives are based in his insatiable hunger for power. The argument goes that Putin, a former KGB agent, feels personally slighted by the fall of the Soviet Union, and is now seeking out revenge through a massive international expansion of Russian power.

In his article, Johnson expresses dismay over the idea that "Putin, who runs what is, in essence, a second-rate nation with a weak and declining demographic structure, behaves as if he rules the Earth." And yet, it is this weakness that gives Putin the desire to act in such a way at all. The assumption that Putin is engaging in foreign military intervention out of a desire to expand Russia's power has it all wrong; he is doing it in an calculated attempt to prevent losing the power that he personally has right now.

The Russian economy has been weak ever since the global financial collapse of 2008-2009, but it's only been within the past year that it has fallen back into actual recession. Their economy began shrinking last Fall and is continuing to do so to this day. The World Bank predicts that, in the whole of 2015, Russia will experience -2.7 percent GDP growth and 15.5 percent inflation.

This collapse is almost entirely the result of oil prices falling to their lowest levels in almost five years. Not only does oil make up a third of Russia's exports, but the Russian government also uses its oil revenue to prop up its domestic economy. The sharp fall in the value of oil set off a chain of events that put Russia into the position it's in today. Though the World Bank predicts that Russia will be able to pull themselves out of recession in 2016 (reaching an anemic growth rate of 0.7 percent), Russia faces much greater long-term issues.

First and foremost among these issues is the matter of population decline. Due to a variety of factors such as aging, low fertility rates, low life expectancy, and net emigration, Russia is expected to drop from a population of 144 million today to 111 million in 2050 and 67 million in 2100, based on status quo fertility rates.

Furthermore, Russia's economic reliance on fossil fuels will pose serious threats to its continued growth in the future. A combination of Russian oil reserves becoming more expensive to develop and massive advances in energy efficiency and alternative energy will only make running an economy on such a foundation more and more difficult. Thane Gustafson, professor of political science at Georgetown, points out what a problem this will be for Putin's political future:

Although Putin managed to win the presidential election with ease this time, in 2018, when he could run yet again, it will not be so easy... The opposition will be better organized, and given the rapid spread of the Internet and social networking in Russia, it will have gained strength and depth outside the capital...

Still, so long as the Kremlin is able to retain the loyalty of the business and political elites and continue running the welfare system on which the majority of the population depends, the regime is likely to remain stable. But sometime in the coming decade -- just when is impossible to predict, because it hinges on so many variables -- the state could well see oil revenues decline, even as its reliance on them grows. Even if world oil prices remain [high], Russia's budget and trade balance surpluses will shrink, and the tide of money that has enabled the Kremlin to meet everyone's growing expectations for the past decade will vanish. Then and only then will the preconditions for the end of the Putin era be present.

With all of this in mind, Putin knew he had a problem. Even with the help of some convenient "electoral irregularities", he'll still need a solid support base in order to win office again in 2018, not to mention to make sure that his party maintains control over parliament in 2016. But how can he do that when his nation is plagued by massive problems which require difficult and politically costly fixes? The percentage of Russians supporting him had fallen from the 80's in 2008 to the 60's in 2013. Then, Europe proceeded to give him exactly what he needed: provocation.

Since its independence in 1991, Ukraine has served as a "buffer state" between Russia and the NATO countries of Europe, putting a space in between them that prevents tensions from escalating. This buffer, however, has been eroding more and more over time as the European Union and NATO seek to bring Ukraine under their influence, giving them an ally right on Russia's border. One example of such a Western diplomatic expansion is the 2013 negotiations between the EU and Ukraine towards an association agreement which allows for much greater cooperation and trade between the two.

Sensing this reach for power, Vladimir Putin countered by convincing the President of Ukraine to suspend the process of signing the EU agreement and agreeing to a Russian economic package of benefits for Ukraine. This led already-heated protests to turn grow larger and become violent, forcing the Ukrainian President to flee to Russia. With Western support, a new government formed in Ukraine.

Here was Putin's chance. He could now tell the people of Russia (with only a bit of exaggeration) that European aggression had led to the overthrow of a democratic country neighboring their own. He responded by annexing the Ukrainian region of Crimea, an area primarily inhabited by people of Russian culture and backgrounds, with the purported intention of protecting said "Russian people" living there. In doing so, he not only acquired the rights to large fossil fuel reserves located off Crimea's shores, but also showed to the Russian people that he was willing to bold, radical action to defend the motherland.

Polling shows exactly how attractive that brand of nationalism is to the Russian people. The Levada Center, a major Russian polling firm, reported that, in October 2014, 64 percent of Russians mostly or completely agreed that Russia is better than the majority of nations and 50 percent said that Russians should support their country even if it's wrong. Only 24 percent thought that recognizing their nation's flaws would make the world a better place, showing exactly how hard a lengthy political debate over systemic national issues would be.

Between January and April of 2014, a period during which Crimea came firmly under Russian control, popular support for Putin rose from 65 percent to 82 percent. This was a policy that would work for him.

Putin continued pushing against European influence in Ukraine by heavily funding Ukrainian fighters sympathetic to his cause, many of whom wished to split off the Eastern half of the country and join it to Russia. And, though their government may virulently deny it, there's a growing body of evidence that Russian troops were deployed into the country, including some selfies taken by the soldiers themselves (I'm not kidding).

This is far from the first time a politician has created a nationalist narrative of foreign encroachment to boost their electoral chances, but rarely is it ever this easy, because rarely is it ever this true. Rather than being a Hitler-esque aggressor, Putin is a shrewd politician looking for a way to avoid addressing his nation's tricky underlying weaknesses. He found one in the Ukraine crisis.

Such a response by Russia should have been easily predictable by the West. Even with the domestic political considerations aside, famed international theorist John Mearsheimer commented that it's just "...Geopolitics 101: great powers are always sensitive to potential threats near their home territory."

And yet, the expansion of Europe's reach occurred anyways, providing Putin with an escape hatch to avoid addressing a dangerously weak economy. Instead of fixing long-term issues by reforming the distribution of oil revenues to invest in a more sustainable economy, opening up the nation to immigrants, or fighting the corruption resulting from government collusion with oligarchs, Putin can now tell the tale of how Russia must elect a strong man like him to defend its borders and its people. By stirring up a proto-irredentist fervor that he is best positioned to exploit, he can even steal the thunder away from ultra-nationalists like the (ironically named) Liberal Democratic Party of Russia. In a nation where 69% of people view the breakup of the Soviet Union as a bad thing, the idea of Russia taking over territory it had previously held is probably an attractive one.

Thinking of Putin in these terms- as a nervous leader looking to protect his own political image by focusing public attention on a threat to their nation's power and making himself seem strong- changes the calculus of how other countries should view Russia's foreign policy dramatically. As Harvard International Relations Professor Stephen M. Walt observes:

Russia is not an ambitious rising power like Nazi Germany or contemporary China; it is an aging, depopulating, and declining great power trying to cling to whatever international influence it still possesses and preserve a modest sphere of influence near its borders, so that stronger states — and especially the United States — cannot take advantage of its growing vulnerabilities.

Walt argues that Putin took action in Ukraine primarily out of a sense of realism. That certainly plays is a major factor, but Putin likely would have intervened even if it wasn't in Russia's national interest. Regardless, the point Walt goes on to make remains: Russia's involvement in Ukraine is following the pattern of a "spiral model", where any attempt to counter Russia will only strengthen their resolve. If, for example, the United States were to involve itself in a major military intervention in Ukraine, Russia would only escalate the situation further, not only because they have a greater strategic interest there than we do, but also because failure to do so would defeat the political purpose of intervening in the first place: showing off Putin's strength to the Russian people.

What makes Putin both so weak and so dangerous is the fact that, now that he's gotten involved, he can't back down unless it appears that he's won in some way. Fighting there may be deescalating now, but to completely pull out of Ukraine before he can show that he's accomplished something would be seen as a sign of weakness which would devastate his election chances.

By moving from a position of being unable to fix the economy to a position of being unable to back down in Ukraine, Putin may have been able to boost his poll numbers, but he still hasn't been able to break himself out of the trap of dealing with problems that have no politically popular solutions. He's becoming paralyzed, running out of options for ways to prevent an erosion of his popularity. Thus, pushing him would be something even more dangerous than backing a bear into a corner: it would be pushing someone who wants to convince people that they are a bear into a corner. He has all the more reason to retaliate in a rasher and rasher manner.

Now, enter Syria. What's happening in Syria is of less interest to the Russia people than what's happening in Ukraine: Levada Center polling shows that only 15 percent of Russians have been closely following the civil war there. And, though support for military intervention may be lukewarm at best (a plurality supports indirect military support, but a majority opposes the deployment of troops), we can assume that Putin is attempting another diversion.

Though it claims that the purpose of its airstrikes are to combat ISIS, intelligence suggests that Russia has also struck both U.S.-backed groups and al-Qaeda's Syrian affiliate, al-Nusra. Though al-Nusra is formally opposed and labelled a terrorist organization by the United States, they effectively benefit from American military aid due to how frequently they acquire weapons, equipment, and even personnel from U.S.-backed rebels. It's not extremely uncommon to see fighters who had received U.S. support wind up joining groups like al-Nusra, a fact that Putin is acutely aware of. In his U.N. speech, he spoke of how "the ranks of radicals are being joined by the members of the so-called moderate Syrian opposition supported by the Western countries". This hints at Putin's intentions: he's targeting both ISIS and those that he views as Western-backed threats to the Syrian government.

Ultimately, Putin aims to do three things in Syria: sell Russia's fight against ISIS as a fight against Western trouble-making to voters, provide support for the Syrian government, and emphasize his own machismo and power as a leader. He views Syria as a similar situation to Ukraine, where he can use force to stand up for Russia and its national interests.

The problem is that this simply can't continue for ever. Putin might enjoy the economic benefits that come from heavy military spending, but military Keynesianism is not itself a long-term economic plan, and may even do damage if it creates an issue with debt when mixed lower government revenues. The problems of Russia's reliance on oil and shrinking population will not disappear on their own.

Polling from this Summer shows that 73% of Russians disapprove of the state of the economy, but 70% approve of Putin's handling of it. People are willing to rally behind Putin and let their national pride overtake the pains of economic hardship right now, but Russian Economic Sociologist Dilyara Ibragimova doubts that that will last forever: "I think that’s temporary, because the continued growth of prices will hit their pocketbooks and affect their attitude."

Therein lies the weakness of Putin: he's so afraid of Russian voters waking up from his pleasant nationalist dream and focusing on the dire state of the economy that he has practically no choice but to try and keep the dream going forever. His choices are severely limited by the political conditions he's surrounded by, and he's left with few options other than to jump into foreign conflicts. He has almost no easy options left except to put enormous amounts of effort into appearing to be a strong leader by focusing on external threats, precisely to avoid being a strong leader, and facing the tougher internal issues.

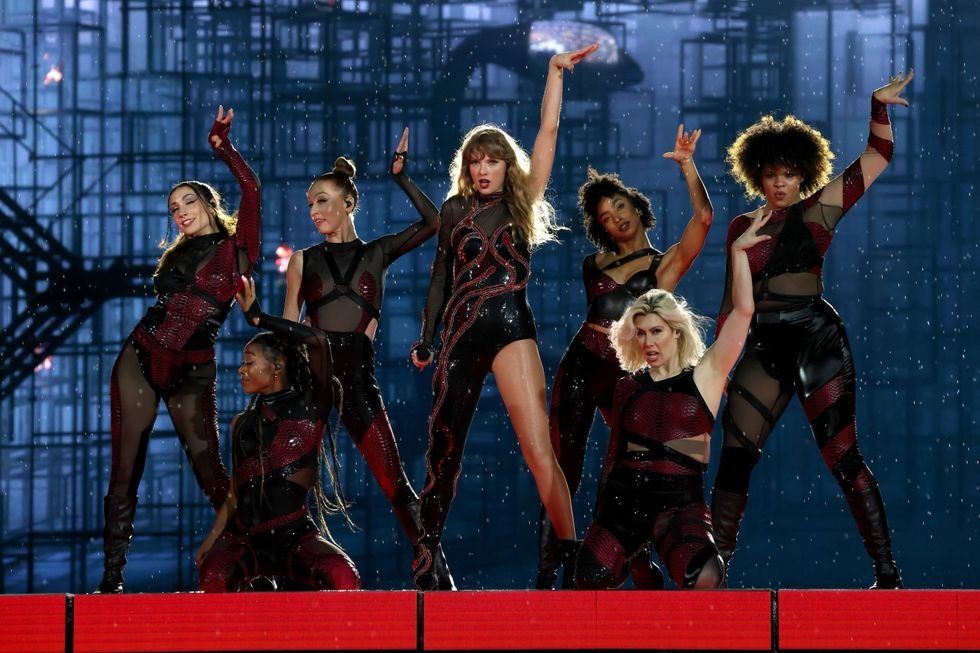

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight.

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight. Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage.

Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage. Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots.

Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots. Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.

Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.