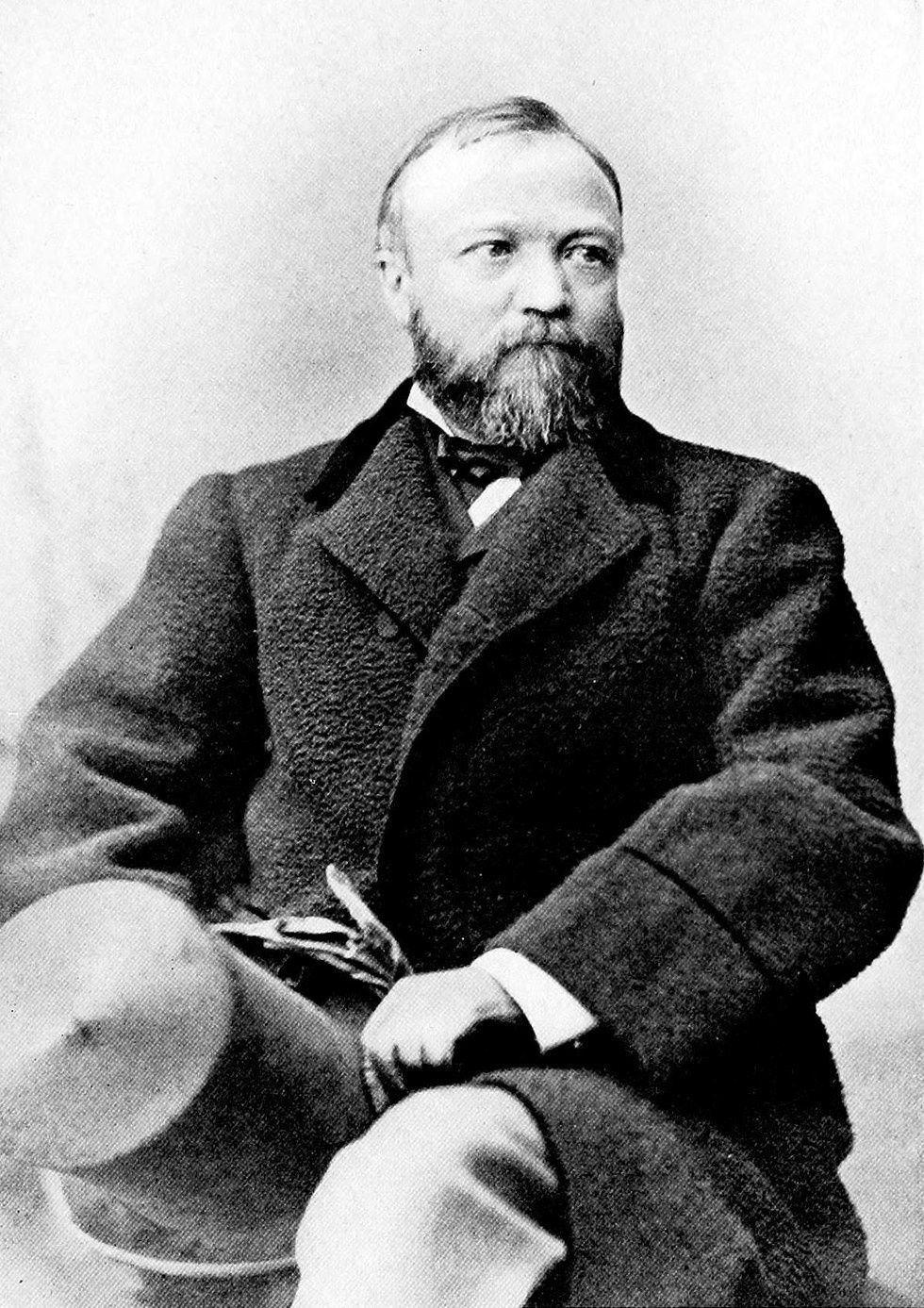

Andrew Carnegie was one of the most successful businessmen to have ever lived, famous for transforming the steel industry and profiting enormously from it in the process. He was also one of history’s most enigmatic men; he was generous with his money on a scale that had never been seen before, yet he was scorned by many and continues to be scorned for his treatment of men who worked under him. The very difficult and daunting task of reconciling these two wholly separate Carnegies was the primary challenge biographer David Nasaw faced when writing his 2006 book, “Andrew Carnegie,” and though he may not have succeeded entirely in this respect, the book is very illustrative of the complex and eclectic life of the Star-Spangled Scotsman.

Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland in 1835 to parents who had almost no money at all to their names. Facing crushing poverty, the family moved to Pittsburgh when Andrew was still a boy, following a stream of other immigrants towards the more promising and hopeful United States. During this time, Andrew was noticeably garrulous and inquisitive, incessantly questioning both his parents and anyone else he happened to run into about everything and anything. His inexhaustible extraversion would remain with him until his dying days, making him one of the world’s greatest and most quotable conversationalists.

With a relentless drive to be the best at whatever it was he was doing, Carnegie wasted no time in making his presence known in America. It was impossible not to like him; his various coworkers and bosses were captivated by his eternal and unshakable optimism. Even after he had retired from business and the world had become embroiled in World War I, he was a staunch advocate of world peace, writing dozens of essays on the subject and traveling back and forth from the U.S. to Europe to meet with world leaders in pursuit of ending all human conflict.

How, then, could such a gracious and peaceful Carnegie have treated his workers so badly? There is no doubt that he was aware of the conditions he was putting them in: 12-hour work days, paltry salaries and exhausting working conditions within his steel factories were relayed to him frequently by his associates. The most telling example of his harsh treatment of his workers, however, came when an increasing number of less skilled workers from Eastern Europe began threatening the positions of the more skilled union workers, which helped to set the stage for one of the most famous strikes in American history: the Homestead Strike of 1892.

Carnegie was vacationing at his estate in Scotland at the time of the Homestead strike, yet even there he could not escape the news of what was happening back in Pittsburgh: a battle between his workers and the Pinkerton National Detective Academy (which was used by Carnegie’s company to control the workers who refused to work) had broken out at his Homestead steel mill and resulted in over two dozen dead and twice as many wounded. Riots had also taken over the area surrounding the mill, at one point necessitating the arrival of the state militia to help quell the Strike. It was nothing short of a war zone, yet Carnegie never returned to Pittsburgh from Scotland during this time, electing instead to write instructions on how to deal with the problem to a top associate.

Amazingly, however, it’s likely Carnegie never thought he was doing anything malicious, or that was contrary to the best interests of his workers. He genuinely believed that his workers were being unreasonable, turning their backs on him when he had always been on their side, showing him no gratitude for his efforts to give them respectable jobs at one of the biggest companies in the world. He was even publicly in favor of labor unions before the strike. However, he also believed that if one was poor, it was because one chose to be so; having risen from poverty to become the world’s richest man, Carnegie held no sympathy for those he deemed possessing a losing mentality that prevented them from climbing the ranks of society, especially in such an opportunistic land as America.

“Andrew Carnegie" is a long but highly entertaining account of the life of the famous (or infamous) steel tycoon, writer, spokesman and informal advisor to many U.S. Presidents. His inconsiderate, if not cruel, actions as a businessman are shown to be in stark contrast to his overwhelming generosity as a philanthropist; he ultimately gave away over $350 million, or $76 billion in today’s dollars, of his own fortune to charitable and educational causes. If you’re looking to learn more about one of America’s most prominent, yet conflicting historical figures, look no further than David Nasaw’s “Andrew Carnegie.”

man running in forestPhoto by

man running in forestPhoto by