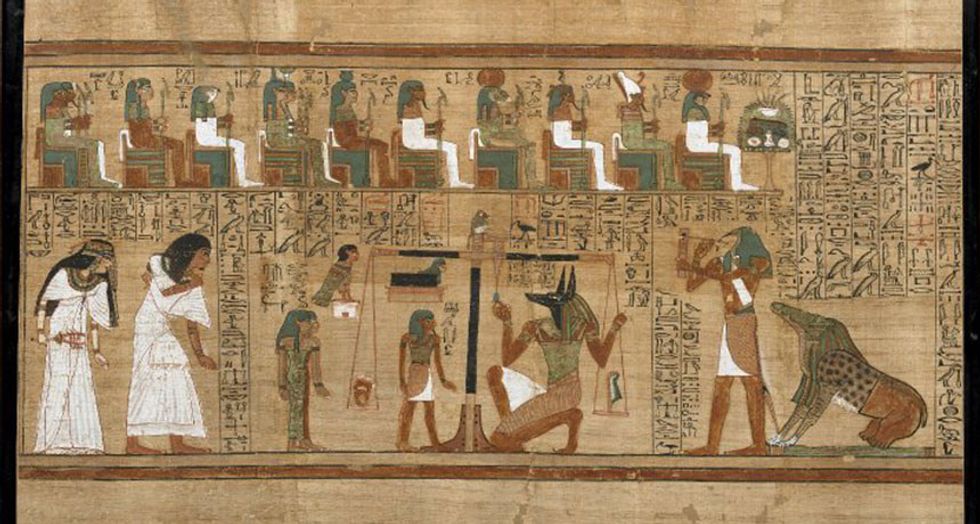

Ancient Egypt had sages like we have scientists. But instead of striving for precision in the description of minutiae, their goal was to explain cosmic concepts to laymen in the clearest way possible. Seleem says, “The Egyptian sages expressed their teachings by symbolic and sometimes mythological figures, thereby avoiding the use of technical diagrams, classifications, and theoretical speculation” (Seleem, Ramses. The Illustrated Egyptian Book of the Dead: A New Translation with Commentary. New York, NY: Sterling, 2001. 11). To Egypt, theoretical speculation was the realm of religion and philosophy. Their science was simply practical and educational.

A science-based culture requires a language that lends itself easily to concrete categories and abstract concepts. Hieroglyphs, known to the Egyptians as Medu-Netru, offer the simplicity needed for this delicate relationship. Ancient Egypt reported that this language was divinely revealed to them, and that it was meant to relate the Word of God through the laws of nature (36).

Medu-Netru is the language of scientific concepts. Its meanings are clear to a public educated in relation to nature. For instance:

“The female crocodile carries its eggs for sixty days and broods on them for sixty days. It has sixty vertebrae and sixty teeth, and lives for sixty years. Number sixty is the basic unit in astronomy and the measurement of time, since the minute is sixty seconds and the hour is sixty minutes. The crocodile, therefore, reflects the principle of time, and in the Egyptian word Sebek, meaning crocodile, the syllable, Seb, means time” (37).

Through easily recognized symbols of plant and animal properties, Medu-Netru provided everything needed for ancient Egypt's highly advanced medical studies, agriculture, politics, technology, physics, and astronomy. But how could such an advanced civilization function with a simple language that reads like a comic book? The key is in its simplicity.

Quantum physicist, Richard Feynman, beckoned modern education to return to such simple roots:

“The real problem in speech is not precise language. The problem is clear language. The desire is to have the idea clearly communicated to the other person. It is only necessary to be precise when there is some doubt as to the meaning of a phrase, and then the precision should be put in the place where the doubt exists. It is really quite impossible to say anything with absolute precision, unless that thing is so abstracted from the real world as to not represent any real thing” ("New Textbooks for the ‘New’ Mathematics," Engineering and Science volume 28, number 6 (March 1965) p. 14).

Feynman goes on to argue that even the religiously

trusted science of mathematics exacerbates this dissociation from reality. The

ability to describe does not equal the ability to understand, no matter how

accurate the definitions. It seems

that as the ages pass the further we distance ourselves from simple cosmic

truths.

We have much more yet to learn from the ancients.