A country’s education system may be one of the most significant indicators of its social and economic welfare. Public education is a crucial method for nations to invest in every aspect of their futures. In a general sense, the ability for students in a nation to gain new knowledge, perform well academically, learn new skills, etc. can hold implications for the extent to which that nation can innovate, advance, and form solutions to some of the most pressing issues in that nation. So, it makes sense that many Americans have debated about and attempted to advance the status of the US education system for decades.

To be clear, the following analysis of the status of America’s education system will not focus on higher education; it will focus on primary and secondary, public education. Because higher education is optional and additional to primary and secondary education, it is the case that those without formal, higher education can still prove useful and valuable for the country’s advancement.

Although data shows that Americans with degrees from higher education institutions only have half the amount of unemployed people as those without such degrees, higher education is not a requirement for success. Individuals have the ability to gain knowledge and skills on their own using whatever means are available, without a need for higher education. As well, there have been many financially successful and intelligent individuals in America who did not graduate from higher education institutions, including Richard Branson, Mark Zuckerberg, and Steve Jobs.

America’s public education system has been under the media spotlight for decades, yet ideas for how it should change are still developing. Some of the biggest issues facing the system are most related to the quality of the curriculum and how well the system is being controlled. In 1958, fears about Russia’s scientific and technological progress led Congress, with the help of President Eisenhower, to pass the National Defense Education Act. This law authorized education funding in the US, which increased each year for four years.

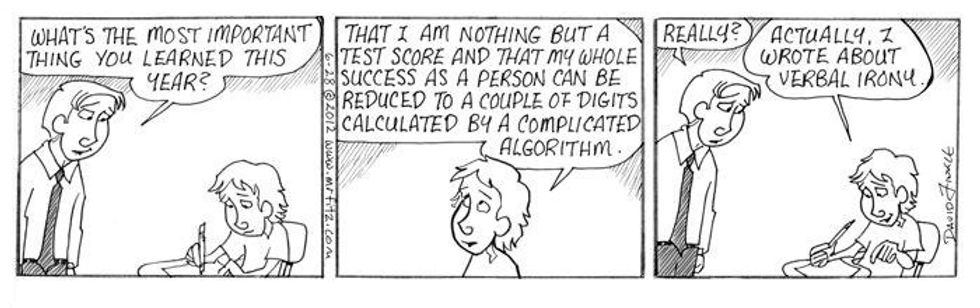

In 2001, Congress passed the No Child Left Behind Act, legislation proposed by President George W. Bush, which established a system of standardized assessments, increased the federal government’s role in education, and allowed individual states to form their own achievement standards for students. However, the legislation has undergone much scrutiny over the years and, as of 2015, the law was rewritten to form the Every Student Succeeds Act, which essentially narrowed the role of the federal government in the education system.

Regarding America’s education system, the Common Core State Standards Initiative may be one of the most contested topics of discussion in recent years. It is an education initiative proposed in 2009 that attempts to set the expectations for the knowledge that students in every grade, from kindergarten to grade 12, should have before entering college or the workforce. While there has been criticism and support for the plan since its inception, no new initiatives or pieces of legislation have been passed to set changes to or replace the Common Core.

In spite of the government’s interest in strengthening the education system, some research shows that the US still has plenty of room to do better. In comparison to other countries, the US is perhaps not even in the top 10 for best educated students. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) conducted a 12-year long study of 65 countries between 2000 and 2012. According to their results, the US has a math literacy that is lower than 29 countries, a science literacy that is lower than 22 countries, and a reading literacy lower than 19 countries.

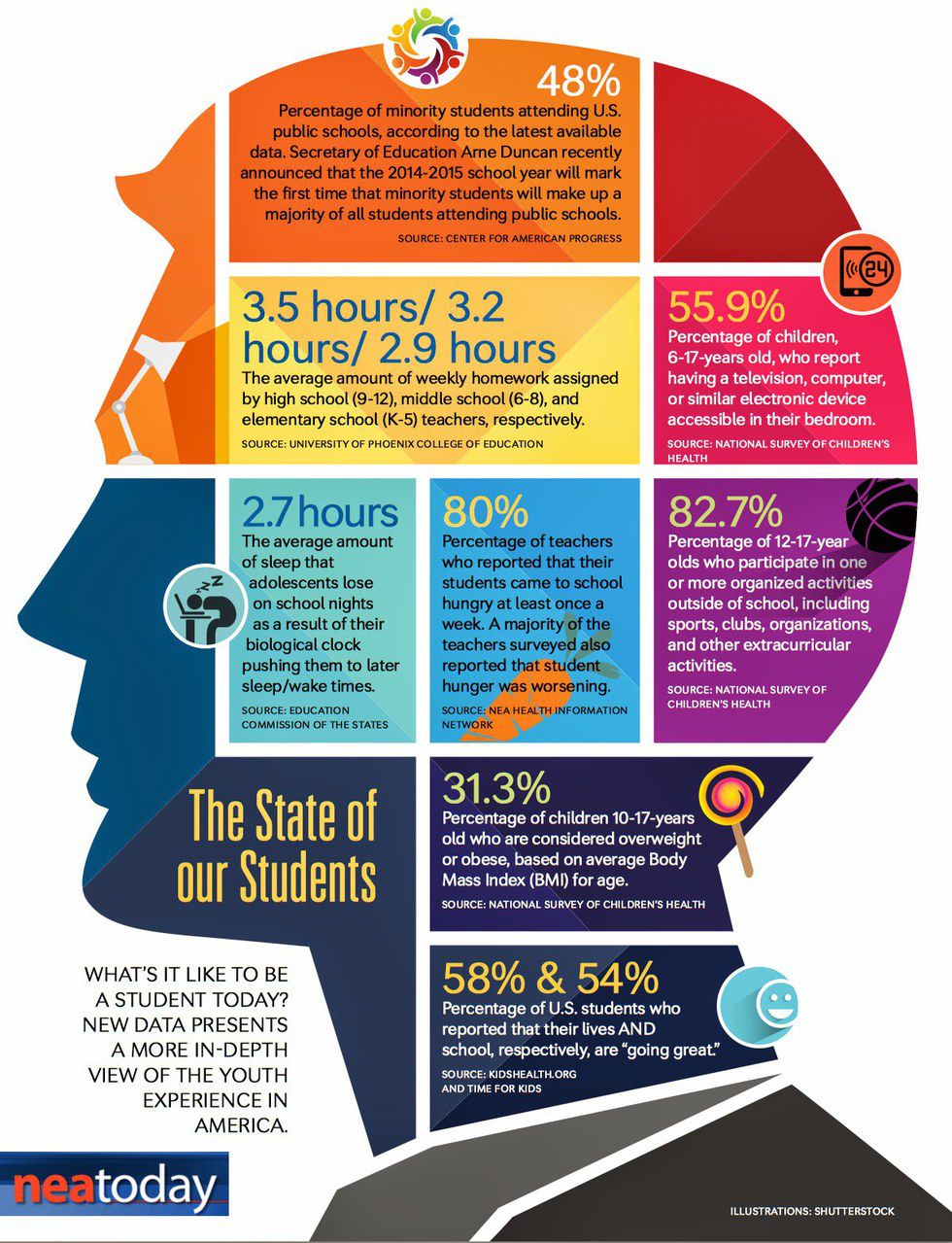

As well, although spending in American public schools has increased by 663% since World War II and, between 1950 and 2009, the number of staff members has increased by 386% and the number of students in public schools has increased by 96%, academic performance has not improved very much. Also, between 1970 and 2000, graduation rates in public high schools in the US have seen a gradual decline.

However, some researchers do not believe that referring to America’s education system as “failing” is unfair. According to some experts in the fields of education and economics, America’s socioeconomic status has proved to be burdensome for public schools. By comparing test scores in multiple countries and adjusting for academic resources in different households, these researchers found that disadvantaged American students have made more progress over recent years than those in even some of the highest-ranked countries. They further estimated that the score gap between US students and those in the high-ranking countries shrinks by 25% in math and 40% in reading after adjusting for gender, age, parental education, and available academic resources.

It could also be the case that US schools are hard to adequately compare to other countries’ schools because some other countries take a completely different approach to education. Education funding is one general idea that illustrates some key differences. American public schools are controlled by state and local governments, but they receive funding from the federal government. Private schools are not federally-funded and, therefore, have more flexibility with their fund allocations. However, some other countries, like the Netherlands, allow private schools to receive public funding; as well, some countries’ private schools, such as Germany’s, still have nationally-mandated exams, curricula, and teacher pay scales.

In addition, it is clear that different factors influence the quality of education that students receive. Parental involvement, teacher wages, cultural and environmental influences on students, the means through which students are taught, etc. are just a few. For example, public schools in low socio-economic environments are more likely to receive less funding and could potentially even hold lower graduation rates, instances of parental involvement, etc. Such an environment works to the detriment of these students because their tools to succeed are limited. The determination of America’s education system requires an adjustment for all factors when attempting to claim what country is better than another.

Within the scope of just the US, one could still argue that the education system is not improving solely because it has not changed very much. If you truly consider it, American public schools follow a very similar structure to that of factories from the industrial era. Students go to school for eight hours a day, including a roughly hour-long lunch break. Students are organized in “batches,” age groups for different grades. Bells are used to indicate how far along the schedule the individuals are. As well, as figurative “products,” students are measured by their product quality: their grades. There is not enough attention to individual student differences, such as whether certain students function better in small or large groups, or whether students are better-suited for certain subjects or environments.

Many of my notions about the education system in America are modeled after those of Sir Ken Robinson, an author, speaker, and professor. In a TED Talks video, entitled “Changing Education Paradigms,” Robinson explains how many young students are being alienated by the education system in the US. A person’s education level, unlike in previous generations in America, is not a strong determinant of future success. He says that “the problem is that the current system of education was designed, conceived, and structured for a different age… the [era of] the industrial revolution”; he later claims that the “system of education is modeled on the interests and image of industrialization.” The underlying assumptions in the resulting model of public education holds that academic ability is the measure of intelligence, which limits and undermines individuals with different kinds of intelligence.

Robinson further expresses how children live in “the most intensely stimulating period” in history; they are “besieged with information and pause attention from every [technological] platform,” but they are “penalized for getting distracted.” By “penalized,” he refers to the increasing numbers of students who are being diagnosed with ADD and ADHD, potentially as a result of a lack of focus in school. He believes that the education system places a higher value on specific kinds of education because those with a lack of interest or the inability to pay attention to them are often thought to have a problem: an attention disorder. For him, this system places little weight on the aesthetic experience expressed by the arts, in which the senses operate at their peak, because it defers to a fixed mindset about intelligence and talent.

However, he proposes a solution, which I agree with; he calls it “divergent thinking.” Divergent thinking holds the capacity for creativity, where someone can see and interpret a question and answers to a question in different ways. All people have this capacity, however, it deteriorates as we get older because of the education system. He says that “we need to think differently about human capacity,… recognize that collaboration [is significant to] growth,” get rid of ideas that limit the divergent thinking within students, and focus on the culture of America’s institutions. This could be a key method for America’s education system to better service America’s students and, thus, the future of America.