By this point, many of us have heard about the Brock Allen Turner rape case. In January of 2015 Turner was found thrusting himself onto an unconscious and doubly inebriated woman. I find, within myself, the most peculiar of curiosities while scrutinizing side-by-side images of Brock Allen Turner and countless others accused or convicted of the same or similar crimes – rape. For quite some time, the media opted not to release less than favorable images of Turner, even extracting a high school yearbook picture of him smiling in exchange for a proper mug shot. I find this, of course, to be the most minor of offenses when concerning the manipulation of the Turner case by the media.

The peculiar curiosity I speak of has left me with a grievously hardened and, quite honestly, habituated heart apropos of the prejudiced and, surely fraudulent judicial system in the state of America. This is, ultimately, the same system that has bore, harbored, and stimulated the Brock Allen Turners that it has so vehemently sworn to bring to justice. It is, ultimately, the same system that has beelined toward opportunities to barbarize others who have been accused and later convicted of the same or similar crimes. This, of course, is not taking into account the treatment and barbarization of those accused and convicted of lesser crimes. These people do not look the same as Turner.

Only the most bipartisan of observations could shed light on what I presumed to be the true pervasive problem of rape culture – which I would have been glad to be a part of – but one would first have to come to the realization that the machine principally exists. Even one of the largest anti-sexual assault organizations (RAINN) in the country asserted, in a 16-page letter to the White House,

“In the last few years, there has been an unfortunate trend towards blaming “rape culture” for the extensive problem of sexual violence on campuses. While it is helpful to point out the systemic barriers to addressing the problem, it is important to not lose sight of a simple fact: Rape is caused not by cultural factors but by the conscious decisions, of a small percentage of the community, to commit a violent crime.”

RAINN president Scott Berkowtz and vice president Rebecca O’Connor have hit crucial points worth noting. Rape is, in fact, the byproduct of “…the conscious decisions made by a small percentage of the community," but this in and of itself doesn’t explain the Turner case phenomenon. It certainly doesn’t bring into consideration the outside forces or “systemic barriers” at play during this particular case and the media coverage of it. To closely examine the culture surrounding an event we must not singularly look at the accused – the rapist – or the victim, but we must take into account the systemic occurrences that have been proven to be unavoidable at best. All things considered, rape is fundamentally a heinous act, to be punished by the law. But to what extent is the question that only “systemic barriers” hold the answers to.

Turner was allowed to be identified as a 20-year-old Stanford student and champion swimmer. The Washington Post, in a recent article, even coined him the “All-American swimmer.” In the same article, the writer, Michael E. Miller, finds within himself the ability to divulge the details of Turner’s life, including Turners future plans, when he could or couldn’t vote, and even including how “baby-faced” Turner was. Turner was allowed liberties that others like him (in some regard) were not. He was called a suspect, although two men caught him in the act. He was called a suspect after attempting to flee the scene of his crime.

He was so deeply humanized by the media after finding great success in dehumanizing and humiliating his victim.

Cory Batey, on the other hand was not awarded these liberties. Batey, a former Vanderbilt football player, made a similar decision to sexually assault an unconscious woman after a night of partying and drinking. There was ample evidence placing him at the scene of the crime – security cameras, cellphone pictures and video. There was no disputing it. Although Batey confirmed that he did not remember the night of the assault, he did correctly identify himself in the videos shown in court, and took ownership of his actions. Consequently, Batey was sentenced to a mandatory 15 to 25 years in prison.

Conversely, Turner, who also was found guilty of three criminal charges of rape, was handed the most softhearted sentence imaginable. Six months in a county jail with the prospect of early release with good behavior. Not even a prison sentence. I am by no means saying that the Batey, too, deserves this type of treatment, but where is the justice? Is this the same system?

A heavier sentence would have had “a severe impact on him” and he “will not be a danger to others.” The absurdity of the judge’s words is outright egregious, but telling. Another case comes to mind – that of Brian Banks. Banks was a 16-year-old football star at Polytechnic High School in Long Beach, California, when a former classmate falsely accused him of rape. After being tried as an adult, with no possibility of any physical evidence appearing, he was sentenced to a maximum of 41 years in prison. With the truth finally out and the charges were overturned, Banks was released, but by then he had spent five years and two months in a state prison. I find it utterly inexplicable that someone like Turner could find himself practically called everything short of America’s sweetheart while I can’t find one good thing online about the former life of an innocent man like Banks. In court, Turner was offered sympathy because of the severe impact that prison would have on his simple, sheltered life. What about the impact he’s had on the victim? As a writer, I find it my duty to approach these cases with an opinion that is as unbiased as the sky in blue, but not this time. It is clear to me that all of these individuals do not coexist under the same or similar judicial system.

Turner was awarded a system that is sympathetic to what he, a convicted rapist, would feel during his time of retribution. He was awarded a system that is more concerned with what favorite foods he wouldn’t be able to eat if he were in prison for too long – instead of offering that compassion in the victim’s direction. He was awarded a system that is more interested in getting to know the minuscule details of his swim times than bringing him to admit his actual role in the disfigurement of a young woman’s life.

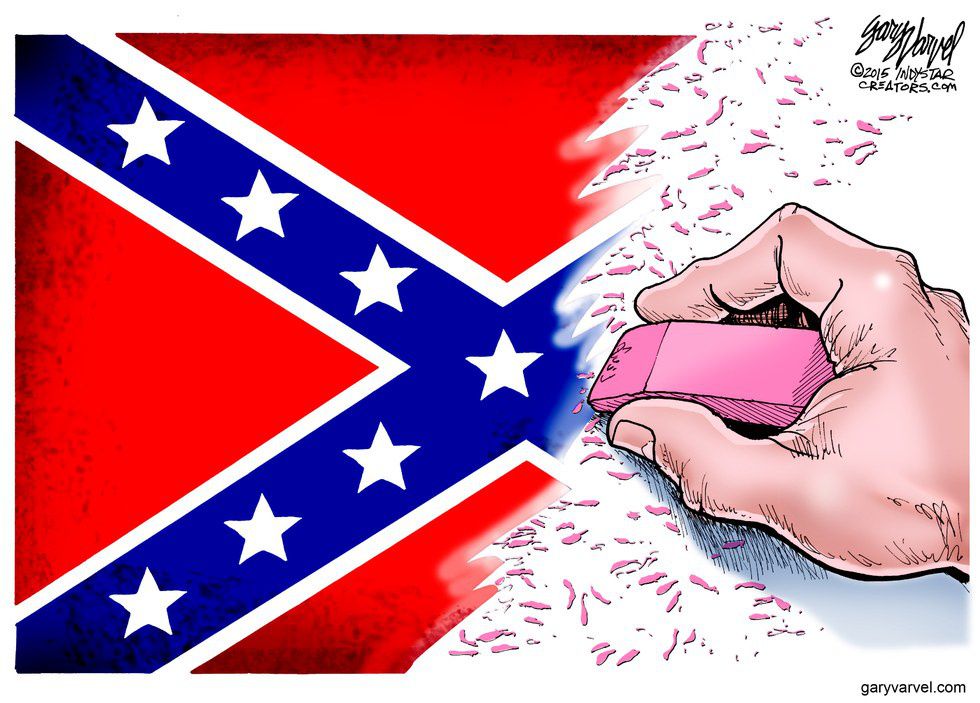

I stand confused. Really. Of the total prison population, 43 percent of that is made up of black people. Of those in state prisons, 58 percent are there for drug-related offenses. We make up 12.6 percent of the U.S. population, but about 43 percent of the total prison population, where we spend virtually as much time in prison (for drug-related offenses) as whites do for violent offenses. I am concerned that our judicial system can align itself with a rapist – a violent offender, I might add – a socioeconomically privileged young man with a good swim time by calling him “All-American,” but doesn’t think to get to knows the lives of countless blacks who have chosen nonviolent routes as their mode of criminal activity. Were the 58 percent of black juveniles that are admitted into the prison system questioned about their swim times, questioned about their favorite foods? Of those who were tried as adults, how many were told that their sentences might be too “severe”? The number of unanswered questions is almost as disproportionate as these incarceration rates themselves. There needs to be a time where cries of Affluenza are a thing of distant past.

Our current system says that a rich white kid has no business being in prison. He’s not prepared. His carefully prepped life is carefully examined because something must have gone wrong on his “All-American” path. His whole life is ahead of him, but a poor, underprivileged, 16-year-old black kid… from Los Angeles… is better equipped for a life in prison among men. By these standards and statistics, one might conclude that poor black kids across the nation have been preparing for life behind bars all their lives – waiting in line to be picked off one by one. What life do they have ahead of them? I have tried to imagine what it must have been like for an innocent teen, like Banks, but I can’t. I shouldn’t have to.