It seems like the only thing I do these days is scroll through social media in a desperate attempt to gain information. My phone has called me out on my screen time more than once, and I just continue to ignore it. You're probably in the same boat — stuck at home, scrolling deeper and deeper into a hole of conspiracy theories and possible "back to normalcy" dates, hungry for information.

While we know that the news is not our mental health's friend these days, getting reliable information is helpful and necessary.

While the rest of us are home on our phones, healthcare workers are on the coronavirus (COVID-19) front line every single day. They see what we read snippets of, quickly gaining the perspective that we couldn't fathom. That's why we're going to the root of the information — these healthcare workers who put their own safety at risk every single day.

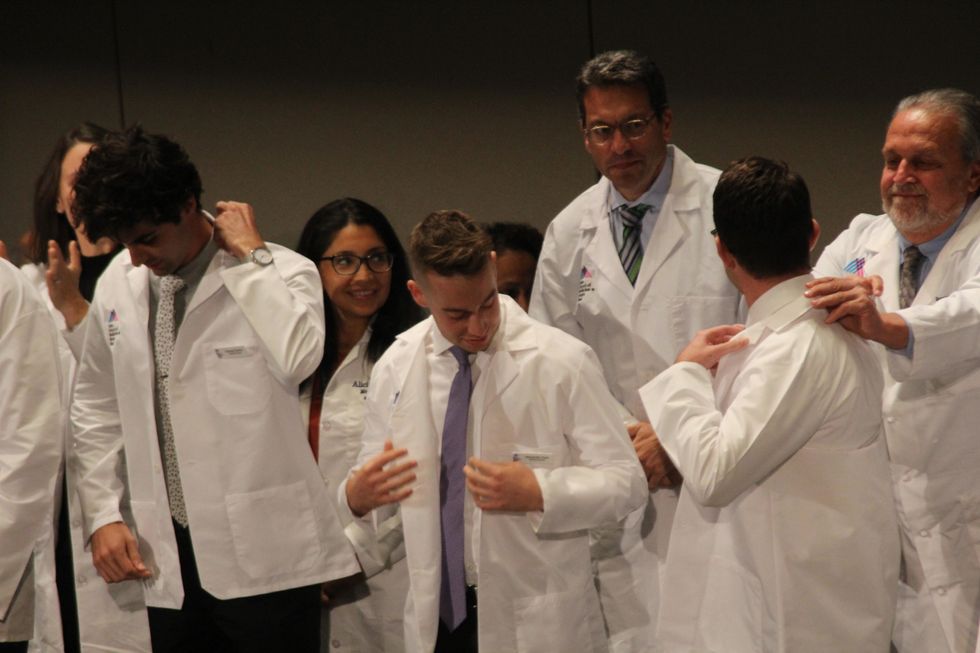

Today, I sat down (virtually) with Alexander Dash, a medical student working in New York, New York.

How long have you been in the medical field?

I'm currently a first-year medical student. Before matriculating to Mount Sinai, I did research at the Hospital for Special Surgery in NYC for two years.

What city is your hospital located in?

I'm a student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, which is located on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, New York. There are eight different Mt. Sinai campuses in the greater New York City area — as students, we rotate to all of the different sites.

What is your hospital's procedure regarding COVID-19 patient care?

New York City has been the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak in the United States. Mount Sinai had the first confirmed case in New York City so, within about a week of that diagnosis, all of our classes were moved to a virtual format. By the middle of March, they removed all of our students from the wards/hospital floors. There were no more elective surgeries allowed, as the hospital became reserved for COVID patients and those requiring emergency care. A group of our med students graduated early in order to help out on the front lines, but the rest of the student body is not responsible for any direct patient care.

There have been a lot of discussions in terms of the role that medical students should play in this outbreak and the best ways for us to get involved. It was determined early on that because of limited clinical knowledge we should not be directly on the front lines. That being said, a group of students began organizing different tasks that are able to take place behind the scenes. While we haven't been involved with "direct" patient care, we have been responsible for building ventilators and distributing personal protective equipment (PPE), conducting telehealth visits, helping prep new patient rooms, participating in research, and delivering medications from our pharmacy to chronic care patients who no longer come to the hospital due to risk. I was lucky to help stock the field hospital in Central Park as it was being built.

As of April 19, students had volunteered over 15,400 hours at seven of our hospitals and have been so important working behind the scenes. I am so proud of all of my friends who have been working since day one and have essentially put school on the back burner to help with our city's effort. Being able to see the care and compassion of my classmates has reaffirmed my decision to go into medicine and makes me proud to be surrounded by such exceptional people trying to save lives in whatever capacity they are able.

The work I've been able to do (and will be contributing to in the coming weeks) involves helping run a prophylactic (pre-exposure or infection) clinical trial at the Hospital for Special Surgery, as well as another study collecting blood samples from in-patients with active COVID-19 infections. My old boss asked me to help her with these projects and with my background in the research, I figured it was a way for me to give back. I hope to get a better sense of how the disease works and we can prevent these infections in the healthcare workers who are still seeing patients every day.

What is the protocol if you (or another healthcare worker) were to show signs of infection?

For medical students, we are just supposed to quarantine ourselves. We have access to telehealth services through medical school and I know that a number of us have experienced exposure or sickness. Since we aren't seeing patients and most of us are young, they just want us to follow CDC guidelines in terms of self-quarantining. If we get sick enough, then, like the rest of the country, we're advised to go into the hospital.

Do you have enough PPE?

The hospital has done a relatively good job of keeping PPE stocked. I had heard there were some problems during the peak of the pandemic in NYC, but I don't know the specifics. I heard from some doctors that gowns were relatively sparse at the hospital and there have been a lot of creative solutions by the staff. However, I have not experienced this shortage personally.

What is the biggest change your day-to-day has faced because of COVID-19?

Alexander Dash

The short answer is the drastic change in how we are now learning medicine. The general structure of our school (and a lot of other medical schools in the country) is that lectures are not mandatory as they are all recorded and can be watched on our own time at our own speed. However, we normally have between 10-15 hours of mandatory classes, labs, and clinical work that we do each week that requires us to be in the hospital. With COVID-19, all of those in-person activities have been canceled and everything that has been able to be moved online has been turned into zoom sessions.

That basically means that most of our learning is now completely self-directed and solitary.

I think one of the things I've enjoyed so much in my first year in medical school is spending time with my classmates, developing friendships, and building up our abilities as future physicians. In some ways, it feels like the human touch of learning medicine has left and that has been really hard to grapple with. Constantly asking yourself, "how can you REALLY learn medicine when you aren't DOING medicine?" The week before COVID-19 canceled all of our in-person activities, I did my first physical exam of a person who was an inpatient in the hospital. She had an ECG monitor on and I saw a pattern on it that immediately helped me diagnose one of her conditions. In our first few year, they overflow us with information — an apt analogy people use is that in each class we are trying to drink from a fire hose — and getting a chance to practice and begin putting these skills into practice was, for lack of a better phrase, so cool! Being able to see things on the physical exam that were "abnormal" and understand WHY they were abnormal was this gratifying moment that allowed me to realize the enormous progress I've made.

Learning stuff from a textbook is great, but in practice, it can only get you so far.

Trying to continue our education in this environment, in addition to all of the projects and volunteer work that we've added to our plate due to the pandemic, has made it really hard to stay engaged. You feel so busy but also so distant from the people you are taking this journey with and the reason that you came to medical school—to learn how to treat people.

Describe your hospital's atmosphere.

There has been amazing courage and resilience from everyone here. There is so much goodness in the hearts of all of the healthcare workers and students here who are trying to get us through this incredibly tough time. While there has been a sense of pride and resolve, there has been a lot of sadness. There have been staff members who have become very ill and some who have died from the virus. The hospital has been overwhelmed with patients for weeks and as I write this, we still have over 1,000 patients in our hospital system who are positive for COVID-19.

It's a somber and exhausting reality right now.

How do you feel about the national news coverage of COVID-19? Accurate? Downplaying the situation?

I watched a lot of news at the beginning and read a lot, but I've had to stop. I think a lot of the conversation is too political. I know it's cliché but this virus is so insidious and all of the different people giving their opinions — about the economy and the relative seriousness of the virus — is really hard to listen to. A lot of the coverage has been trying to emphasize the seriousness of the situation, the unprecedented nature of what is happening, and I do appreciate that. I don't really think you can downplay it considering this is a (hopefully) once in a lifetime event. I know it's hard to separate politics from anything these days, but focusing on vendettas, rivalries, and political parties is counterproductive considering what we're dealing with.

How has your personal life been impacted by COVID-19?

Alexander Dash

Luckily, my mom and I have both been healthy throughout the crisis. I don't always feel comfortable seeing her since I am still around the hospital and I don't want to compromise her health, but we talk regularly.

Otherwise, I am 24 living in NYC. It's hard having to stop everything. I miss being able to go to restaurants, bars, events, landmarks, and museums in the city. It is hard having to change my life to one where I am inside almost all of the time. Not being able to see my closest friends has been really hard and living alone now, it is pretty isolating. Everyone is going through similar struggles but doesn't make it any easier or the restlessness any less difficult to deal with.

What do you wish you could tell the country about COVID-19?

At the end of the day, people are dying. Healthcare workers — people we all know and care about — are risking their lives and that is all that should matter. Our parents, grandparents, friends, family are all susceptible to this virus and I have personally known a number of people who have lost family members to COVID-19, in NYC.

Nothing like this has happened in our lifetimes. Ever. We interact with doctors all the time, they teach us and take time out of their busy schedules to help us learn and become the next wave of people who will one day be able to both treat people and respond to these sorts of crises. The anguish and sadness on the doctors' faces that we interact with tell us so much more about this crisis.

I know that everyone wants to look forward, talk about reopening, and think about better times. I do too. I talk about it with my friends. I want to be able to live a normal life again, but I don't want to do it at the detriment of people who I look up to and who have already given so much in the last few weeks to save as many people as possible.

Are there any stories of hope you can share with us?

It's hard to fully emphasize the incredible efforts that my classmates, colleagues, and professors have undertaken in the last few months. There is a shared willingness to forge ahead. Almost everyone I know stepped up in their capacity to help with the effort, finding ways to assist either at their homes or their medical schools. We had to turn our entire medical school curriculum into an online format and the course directors were able to make this incredibly difficult adjustment and provide us with a warm, welcome, uplifting environment for us to learn — even as the pandemic has raged on in NYC. One of my mentors made herself available to us at all times of the day to talk. She continues to prioritize us even though her wedding was recently canceled. She's been on call for 12 straight days due to the sheer number of patients coming into the emergency room and the number of her colleagues falling ill. Alumni of our school are donating meals three times a week to the students who have remained on campus and are still around both finishing up the school year and helping with the relief effort.

Even with this tragedy unfolding around us, you can see the good in people.

It makes you realize the sort of individuals who are going into healthcare and makes you really proud to both be a part of the field and hopeful for the future of medicine. There are a lot of budding leaders who are going to change the world.

If you are a healthcare professional interested in sharing your story, please email lily.moe@theodysseyonline.com.

Alexander Dash's mother, Deborah Dash, is Odyssey's HR and talent director.

As an Amazon Affiliate partner, Odyssey may earn a portion of qualifying sales.