Let's talk about the term authenticity as it applies to African art. The term authentic is usually only applied to African art if the piece of art in question is anonymous, traditional, and abstracted. However, these qualities reflect the implicit values of the society that designates something as authentic —in this case the oppressive, colonial powers of the West— while they have next to nothing to do with the societies that they have come to represent.

One of these Western values is a teleological belief—that is, the idea that everything moves in a straight line toward a definite end— that imposes a self-centered narrative structure upon the cultures oppressed by Western imperialistic forces. However, this linear narrative, which is assumed in Western culture, is not inherently present in all African cultures. For example, the Yoruba people of Nigeria believe in a more cyclical and transient passing of time and energy, in which our world—the aye – is separated from both the state of transition between worlds and another form of existence that westerners would most comfortably refer to as the afterlife, which Yoruba people call orun. By enforcing a linear narrative and disregarding any other possibilities, Westerners became ignorant to cultures that they did not know enough about and managed to reduce these cultures to plot elements in the grand narrative of civilization’s Western genesis and global spread.

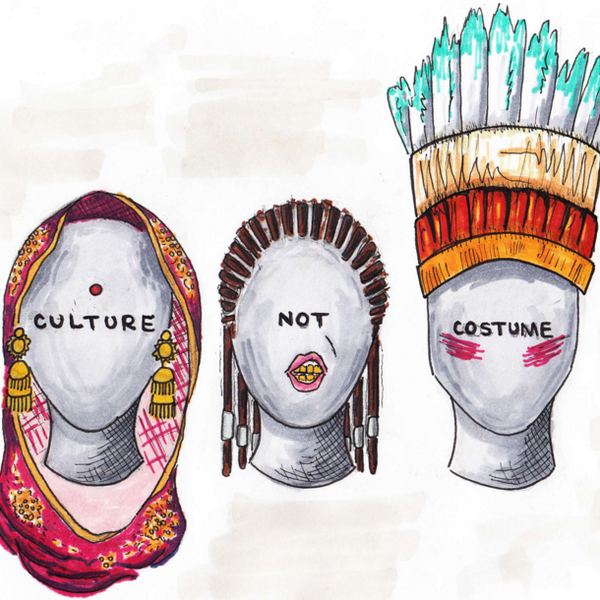

Assumptions like these are acts of purposeful ignorance on the part of the imperial forces in order to keep the colonized cultures from becoming distinct, individualistic, or in any way human; by requiring anonymity from the artists of these cultures, their art becomes a reflection of the collector instead of the creator. This is the ultimate act of cultural appropriation, wherein a culture’s art—which is a physical manifestation of the culture’s values and ideals—loses its ability to do cultural work because it has been taken possession of, refocused, and decontextualized by an alien culture. Through this act, the art becomes less powerful as a tool of cultural progression. Chika Okeke-Agulu echoes this idea in his article “Modern African Art” by asserting that “The notion of artistic freedom was antithetical to the ethos of colonialism” because “modern artistic subjectivity is linked to political independence” which colonizers would have seen as a dangerous tool. Instead, an appropriation of cultural forms took place, leaving in its wake the idea of authenticity as a designation made by the beholder instead of the artist.

By giving themselves authority over the value of African art forms, Western art critics and curators created a dangerous ultimatum for African artists: work toward cultural progress under threat of silence from the international art community, or reproduce the art of your culture’s past as if its present and future were static continuations of what existed when it was first introduced to Western eyes.

This threat of international ignorance was a way of imposing a self-centered narrative structure on African peoples and reducing them to influences on Western artists and their modernist tendencies instead of allowing nonwestern cultures to have their own nonlinear narratives. The continual misunderstanding—or, more aptly, the refusal to attempt an understanding— of African art by Western audiences lead to its stereotyping and a belief by the Western world that African art could only tell one story. The intrusion of a Western structure on African cultures, and with the moment of initial interaction with the colonizers in the climactic position of African cultures’ progressions, it is implied that, from this point on, they will only rot.

Unfortunately for the imperialistic powers, the “traditional African society” that it seeks to conquer does not exist. In fact, it is helpful to query the word ‘traditional’ here, which is a central tenet of so-called authenticity in African art, because it really has very little to do with African society when uttered by Westerners. Tradition from the point of view of its practitioners is timeless and comforting, but the same word coming from an outside perspective becomes almost patronizing by assuming that the way a culture behaved when it was first observed is the only existence it has ever had.

This process of refocusing African art on its Western consumption has required African artists to confront their need to reclaim authenticity. This has resulted in an African modernism that resides outside the Western definition of authentic because, in Okeke’s words, “African modern art does not propose a particular narrative of modernism, as the triumphalist European version did.” As African artists look toward the future of their cultures, they open themselves up to a variety of narrative structures—indigenous and assimilated—that are possible, instead of confining themselves to the decline promised by imperialist constructions. Artists at recently established African art schools—themselves proof of an agency that was impossible under colonial rule—are “concerned with the role of the artist in a culture in transition” according to Okeke, meaning that they have all heard the same message loud and clear: do not succumb to the forced anonymity and teleology of Western thought; rise and fill in the outlines of your own individuality. These students inhale the many influences of their cultures’ pasts and exhale a future of many winding paths, each as authentic as the other. Their reclamation of authenticity is therefore political-literary move toward independence and the right to their own, possibly nonlinear, societal structure.

So we have to stop allowing ignorance and reductivism (and therefore imperialism) to persist. We must educate ourselves and our friends, all the while learning to think with a little more relativism. And we need to seek out a variety of experiences and expressions of those experiences so that we don't limit ourselves to a single, hegemonic narrative. If you haven't already seen Chimimanda Ngozi Adichie's wonderful TED talk on the topic, I suggest you start here.