Back in 2013, during my first semester at Teachers College, I was taking a class called "Disability, Exclusion, and Schooling." In this class, I got the opportunity to reflect on my own experiences as a person with a disability navigating the United States school system, as well as gain a complete understanding of disability rights, history and my identity as it related to the two. Before taking the class, I had never really known about or attempted to immerse myself in, any type of disability activism. Furthermore, I had absolutely no idea that fields like disability studies in education existed.

At one point, our professor, Megan Lawless, had us read an article by R.G Thomson called Disability, Identity, and Representation. In this article, Thomson asserts that the physically disabled are “produced by way of legal, medical, cultural, and literary narratives that comprise an exclusionary discourse” (p.6). She also argues that disability is a representation, a cultural interpretation of transformation or configuration…a product of cultural rules about what bodies should be or do.”

Disability is a product of cultural rules about what bodies should be or do.

Furthermore, those rules can show up, either overtly or covertly, in varying forms of popular media including, but not limited to, literature, movies and graphic design logos. In literature, for example, Thomson states that “disabled literary characters usually remain on the margins of fiction as uncomplicated figures or exotic aliens whose bodily configurations operate as spectacles, eliciting responses from other characters or producing rhetorical effects that depend on disability’s cultural resonance (p.9). These particular literary interpretations occur because the perceptions and lived experiences of disability are disparate. Due to limited interaction between those identifying as disabled and the nondisabled, the idea of otherness emerges from “positioning, interpreting, and conferring meaning upon bodies” (p.10).

In simple terms, Thomson means that because the non-disabled have little to no real-life interaction with their disabled counterparts, they end up transferring their own, sometimes limited, ideas of disability onto the disability community as a whole. Instead of thinking of people with disabilities as individuals, non-disabled people tend to view them as a group. As a result of this group view, people with disabilities are often considered as having the same limitations and needing the same care, even if they have vastly different disabilities. The fact that non-disabled people operate with this view does not bode well for the disabled because it, in effect, takes away their agency, their ability to do things and make decisions for themselves.

Contrary to popular belief, those of us with disabilities aren’t always waiting for others to do things for us. We want to live full lives, with access to the same spaces (public and private) as our non-disabled counterparts. However, achieving this ideal can be hard when physical space has not been created with us in mind. Public buildings don’t always have a ramp or elevator access. Additionally, I spent three years of graduate school in New York City and know that only a quarter of the subway lines are accessible, only 233 taxis have accessible features, and that paratransit services like Access-a-Ride need to be scheduled in advance and aren’t always on time. Living with these imperfect services cuts out spontaneous adventures and makes getting to work or interviews on time difficult.

And more, the idea that people with disabilities cannot do jobs or contribute to the workforce only adds more difficulty.

Disability is a product of cultural rules about what bodies should be or do.

The popular narrative around disability is that those with disabilities are incapable of doing things for themselves and are always waiting for someone to help them. The cultural rule of a physical body is that it should be able to walk on two legs, transverse stairs or ride on a train without assistance. The body should be able to run, fit into narrow spaces and take up as little space as possible. Do everything on its own.

Do everything on its own. Because that is what the “natural and normal” body was created to do.

But here’s the truth: the disabled body is not natural or normal; it is diverse.

And while I believe that diversity should be natural and normal, at the moment, by societal standards, it’s not.

But here’s the good news: the way that people view the disabled body can be changed. And activists have already begun.

During the same semester in which I took "Disability, Exclusion, and Schooling," a fellow classmate informed me of a group of activists who were working on modifying the accessible icon (the graphic you see on handicapped parking spaces, outside bathrooms etc.). These people, collectively known as the Accessible Icon Project, invested in taking the icon -- pictured as an immovable, motionless body in a wheelchair -- and changing it so that it now looks like the body is pushing itself, using its own power to move through physical space. If one takes a look at the icon, he or she can see that the icon is all about giving agency and promoting access.

I attended an exhibit of the Accessible Icon at a gallery on Ludlow Street, and I was impressed. I went with the same friend who mentioned them to me. I took a cab in the snow, only to reach an entrance that had no access. The organizers told me that they had accidentally left their ramp in Boston, and graciously offered to help me up the large step. (I commend them for taking time throughout the event to go into the basement and create a ramp so that some of us could get out safely near the event’s end) I still have the sculptures I bought and some of the stickers. I even put them on my walker to show support (although they have since been destroyed by the elements).

The Accessible Icon actively works to deconstruct social ideas about what the disabled body should be and do. With a simple picture, the group reminds others that people with disabilities have the power to be active and do for themselves; they don’t have to wait for permission. They have the ability to take up space and shouldn’t feel bad about demanding it.

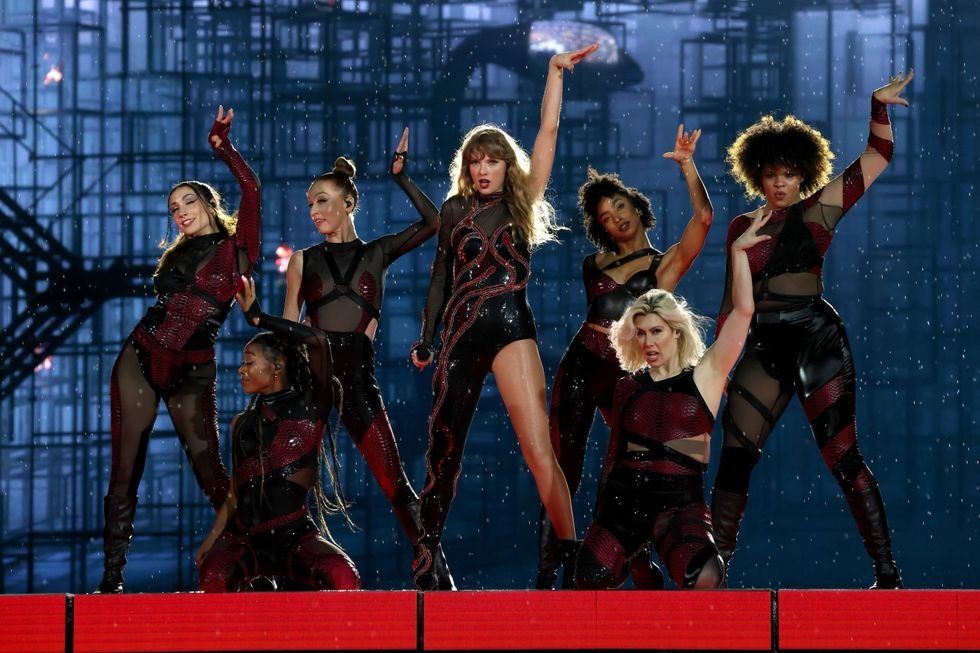

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight.

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight. Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage.

Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage. Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots.

Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots. Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.

Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.