The Greek philosopher Xenophon was born in 430 BCE in Athens, Greece — the earlier years of the Peloponnese War. Little is known about Xenophon's earliest years, but historians know that Xenophon joined the Greek mercenary army of the Achaemenian prince Cyrus the Younger, and was involved in the Prince's rebellion against his brother — the Persian king Artaxerxes II.

He sustained a relationship with the Spartans even after Xenophon's return to Greece. As a result, Xenophon was quickly exiled from Athens.

In exile, Xenophon wrote his treatise "On Horsemanship." These are the oldest writings about equine training, breeding and overall ownership of equine partners. "On Horsemanship" spurred the oldest equestrian sport for the Olympics — dressage.

No Olympic sport today can attest to having as enriching of a history as dressage has. From the book of Xenophon dressage continued to be developed by the military until the fall of the Roman Empire where this understanding and refinement of horsemanship was lost in the brutality of the Middle Ages. Heavier horses were favored for use with heavy armor and weapons, but the Renaissance brought back the need for speed, agility and maneuverability of horses in battle.

This was the age of many of the great masters of classical dressage training, as methods were perfected and recorded in writings and art. Dressage had come to be seen as an important part of the education of the young nobility throughout Europe. Dressage and horse riding, in general, became viewed more so as a character-forming process as a way of expressing their elevated status through elegant parades and displays rather than for military use.

Some of the classical schools of dressage were founded during this newfound time of indoor arena work versus strictly using horses for battle — such as the Spanish Riding School of Vienna (1572) — remained and preserve their tradition and is treasured by equestrians everywhere today.

Such a sport is dressage that it has instilled its roots into almost every popular equestrian sport known today. From three-day-eventing to hunter pleasure and even western sporting events — such as reining and ranch horse pleasure — dressage-esque techniques are used in disciplines that may seem anything but dressage.

The goal of dressage is to develop a horse's flexibility, responsiveness to aids and overall balance while maintaining a calm demeanor; it is no wonder that the word "dressage" itself is derived from the French term meaning "training" as this is the goal of dressage.

A training guide called "The Pyramid of Training" offers equestrians a progressive and interrelated system to develop the horse physically and mentally over time. This system includes rhythm, relaxation, connection, impulsion, straightness and collection — all to make a horse appear pleasurable to ride and effortless for the rider.

This system is also used in disciplines such as western pleasure, reining and ranch horse pleasure to develop young horses and train for suppleness, calm demeanor, flexibility and fitness. Western disciplines often times ask horses to have a more relaxed carriage of the body versus English-type disciplines like modern dressage and showjumping

Reining is a very fast-paced and exciting western event where successful trainers build up their prospective champions with rhythm and impulsion. Engagement of the horse's core and back is essential to training in reining just as it is for dressage. In fact, you could even say:

"Reining is like dressage's first cousin that moved out west for college, bought a ranch and a stetson and never looked back." — John Wilkinson

A lot of reining training to instill self-carriage of the horse uses "long and low" training asking the horse to stretch his neck down low and forward whilst moving forward at a walk, trot, or canter. The goal is to stretch and strengthen the horse's back. This type of back/topline strengthening exercise is used in dressage as well to develop the horse's back and teach self-carriage to engage the core and round the back with the goal to properly carry the rider.

Keeping rhythm with your horse is important to keeping that engaged core and round back. Otherwise, you could slam on their back and cause their collection to fall apart and create a messy and uncomfortable gait.

Successful show jumpers will also use dressage basics to create a foundation for their horse's fitness — after all, show jumping isn't just about jumping over poles.

It is so much more complicated than that. Even with the best genetics or the best rider, a horse is nothing without flat work — even in a sport that is glorified to take to the sky. Teaching a horse how to properly carry himself is vital and is yet another lesson taught originally by masters of dressage who lived centuries ago.

A complaint show jumping and hunter trainers have is taking on horses that were trained by someone who taught the horse to jump, but barely did any flat work with the horse. As a result, these horses are a disorganized and confused mess. They know how to jump high — and really are good at it — but barely have half a brain when the new trainer asks them to slow down their gait and engage their entire body because all they ever were taught was to just go forward.

It may not seem like a significant problem, but when you have 1,000 pounds of horse under you that is a flurry of hooves and was never taught to move their body without stepping on himself, it is a pretty big problem. It goes to show that flat work (aka dressage) is important for teaching a horse how to properly carry himself and his rider — not only for the sake of fitness but for the horse's and the rider's sake.

You teach a horse to slow down at the canter and properly collect and carry himself — you just did dressage. You teach a horse to flex and bend at all gaits — you just did dressage. You teach a horse to properly stretch out his gaits while engaging his whole body — you just did dressage.

The above are training tools used in every discipline to train successful and fit horses that are pleasant to ride, which is criteria in every discipline. Dressage is training as well as a discipline and it really needs to be viewed that way instead of some exclusive thing.

As a loyal western rider, I have often received cross-eyed looks from people when I told them I would take dressage lessons as well as reining lessons. I never really understood it, but I think of an idea as to why.

The equestrian community really has a hard time learning from one another and it creates a stench of arrogance to people outside of our sport. Part of this is creating our own identities of where we stand within our sport as equestrians and which discipline we choose to associate ourselves with.

The above statement is as bold as it is harsh, but hear me out.

It is part of human nature to protect our identity in the face of conflict. Whether it is a conflict as small as other equestrians giving us complicating advice or something as harsh as telling another equestrian their entire sport is cruel, we want to protect what has always been known and felt familiar to us. And part of that can be ignoring educated and logical advice that rings true.

Horses are such complicated beasts so large and powerful on the outside yet can develop problems from such mediocre things. So complicated that it is frightening and stressful when a problem does arrive because can logically think of ten different causes and you could still be wrong.

The same way of thinking applies for training. What works for one horse may not work for another. It's complicated to find what works for your own horse and it can be scary when you think of how this horse relies on you for guidance.

It's like being a teacher for a child that can't speak or really make gestures unless they're having a tantrum. What develops, as a result, is this feeling of only trusting yourself since "you know your own horse best." Which may be a good way to go in a lot of problematic situations, but this also causes a distrust in other's advice even if they're educated.

Part of the only trusting yourself attitude ties in with the discipline you choose to identify with whether you're a reiner or a show jumper. We're a little more apt to trust the advice of those within our own discipline. But if someone were to suggest to a reining trainer to take a dressage lesson to improve their riding skills people would look at you as if you grew two heads.

"I'm a reiner, not a dressage rider! What could I get out of a discipline that isn't even mine!?" Well, a lot, actually.

Considering all of equestrian sport is intertwined with how we train our horses and we all adore our horses, we can all learn from each other — especially from the riders that are in a discipline that is literally thousands of years old.

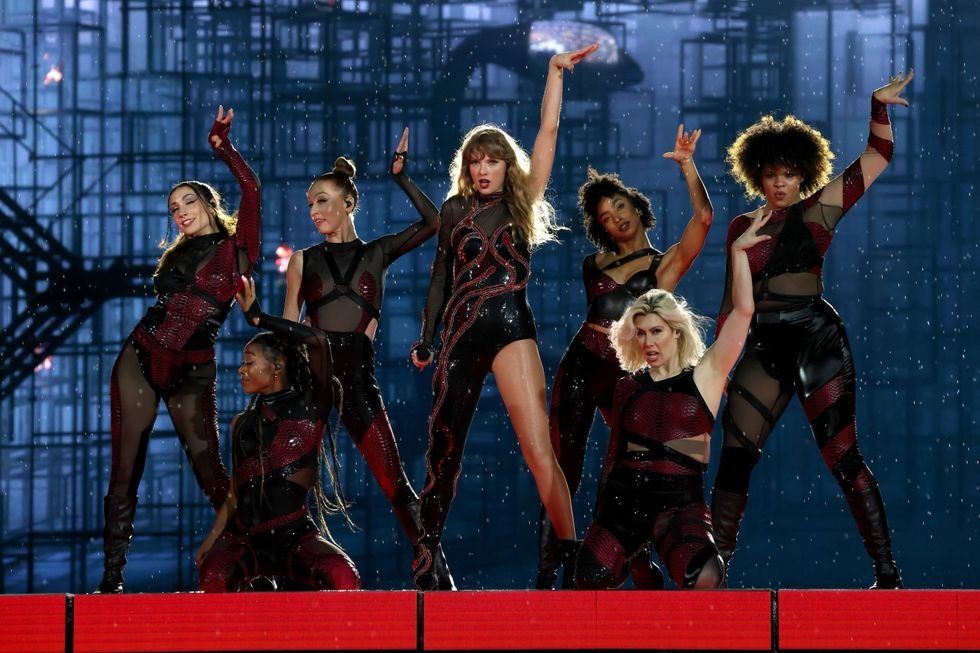

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight.

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight. Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage.

Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage. Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots.

Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots. Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.

Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.