Since the family separation crisis initiated by the Trump administration's zero-tolerance policy by which thousands of undocumented migrant children were taken from their parents so that the adults could be jailed and prosecuted, people have been really angry about immigration.

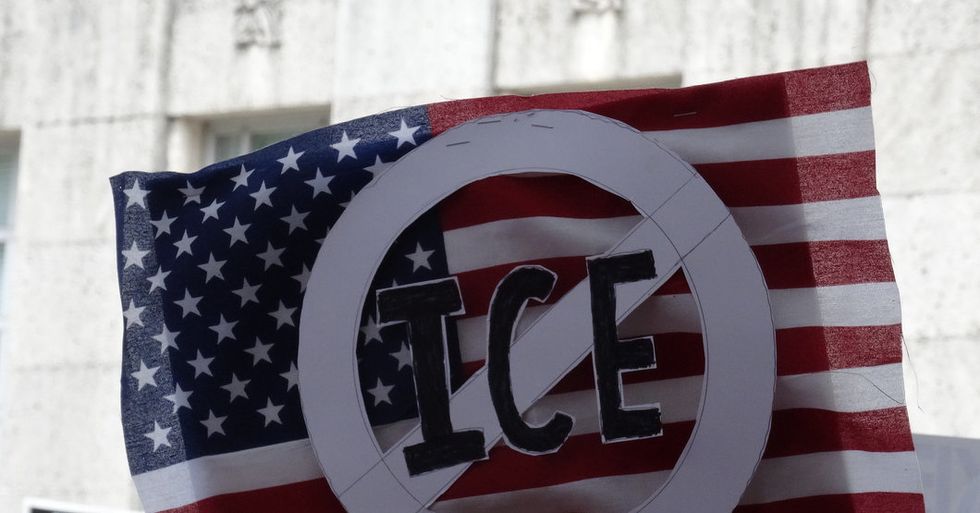

When the administration "solved" the problem by throwing children in jail with their parents (which is against the law), the nation began looking for solutions to the broader problem of the way America treats its newcomers. After a frank assessment of the fact that there are immigration laws, many have called for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which monitors undocumented immigrants already in the country, to be done away with.

Obviously, there is a varied cocktail of small solutions out there that will reasonably reduce illegal entry, humanely treat existing undocumented immigrants, liberalize legal immigration and pass Congress that has yet to be found. But instead of searching for that precise balance of policies, many would much rather deploy a blunt instrument and see what happens.

It is unclear exactly what abolishing ICE would solve, what if anything would replace ICE, or how an ICE abolition bill would pass a Republican House and Senate with a majority large enough to bypass President Trump's inevitable veto, but many congressional Democrats, including Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY), have signed on to the idea.

In response to concerns that the legitimate law enforcement for which ICE is responsible would not be fulfilled if the agency were abolished, liberals respond that ICE is "a relatively new agency," so those obligations must not be very important.

ICE in its current iteration was authorized in 2003 in the wake of the worst terrorist attack in United States history. Its primary objective, like those of a large portion of the other components of the Department of Homeland Security, is national security. Of its $26.6 million budget for fiscal 2017, only $10.7 million was devoted to enforcement and removal operations. Of the 82,000 removals that were conducted that year, 83% were of criminals.

To be clear, U.S. immigration law is messy, confusing and bureaucratic.

A meaningful immigration bill has not been signed into law since 1986. Before then, immigration policy was a function of whichever nationality was the least liked at the time. Today, even though entering the country illegally is a misdemeanor, many Americans treat the action as the highest crime one can commit (see: Jared Kushner's felonious omissions of contacts with foreign officials, which hardly get mentioned by "law-and-order conservatives").

The Trump administration's particular approach to immigration enforcement is only aggravating a bad situation. Before the zero-tolerance policy, immigrants were released into the community under the supervision of a non-governmental organization, a social worker or were given ankle bracelets so they could be active in their communities while awaiting trial, all of which are far less expensive than detaining families indefinitely.

Slapping GPS monitors on migrants' ankles isn't the most humane thing to do, but it's better than throwing them in prison until they eventually have to go home.

There are no good options with regard to immigration. Nor, short of fully open or fully closed borders, are there any quick fixes. But something must be done.

The Trump administration's human rights violations were made possible by a century of a lack of political will, a problem which abolishing an agency responsible for national security will not solve. What is needed is comprehensive, compassionate immigration reform with bipartisan support.

If Congress can't pass a bill, or series of bills, that addresses this critical national security, economic and cultural topic, the crisis at the border will only get worse.